Fußball-Wm 2006 angeblich gekauft

Fußball-Wm 2006 angeblich gekauft

Fußball-Wm 2006 angeblich gekauft

Sie wollen auch ein ePaper? Erhöhen Sie die Reichweite Ihrer Titel.

YUMPU macht aus Druck-PDFs automatisch weboptimierte ePaper, die Google liebt.

MONDAY, JULY 16, 2012 sÜddeutsche zeitung 3<br />

Climbing<br />

Paradise<br />

Forbidden<br />

By ALEX LOWTHER<br />

VALLE DE VIÑALES, Cuba — Here,<br />

the mountains weren’t pushed up from<br />

underneath, as mountains usually are.<br />

In this national park and Unesco World<br />

Heritage site, everything but the mountains<br />

fell down. The mogotes, islands of<br />

limestone, are gently domed, like loaves<br />

of crusty bread, but the sides seem to<br />

have been cleaved off, leaving terrain that<br />

drops precipitously to the valley floor.<br />

In the late 1990s, rock climbers found a<br />

paradise where the walls of the mogotes<br />

are too steep for the otherwise ubiquitous<br />

crawling vines and striving trees. Overhangs,<br />

some 150 meters tall, are covered<br />

with chandeliers of stalactites and blobs<br />

and pockets, all perfectly formed for human<br />

hands and feet to climb from the bottom<br />

of a cliff to its top.<br />

Soon, locals caught on, and a flourishing<br />

climbing scene took hold. Viñales became<br />

a top destination for climbers from Europe,<br />

Canada and the United States. Hun-<br />

Tourism and sport<br />

are threatened by an<br />

inexplicable ban.<br />

dreds of routes went up the major mountain<br />

faces in the valley, and for years visiting<br />

climbers had essentially free rein.<br />

No longer. In late March, even as Pope<br />

Benedict XVI called for “authentic freedom”<br />

in Cuba before an estimated 200,000<br />

people in Havana, climbers here, a threehour<br />

drive west of Havana, the capital,<br />

are wrestling with the prohibition of their<br />

sport, which has been enforced since the<br />

beginning of this year. In an era when<br />

the Cuban government has been easing<br />

restrictions it seems to have moved in a<br />

sharply different direction here, threatening<br />

the prosperity of Viñales and the<br />

future of the sport in Cuba by enforcing a<br />

ban on climbing and regulating independent<br />

tourism in general.<br />

Jens Franzke, a climber from Dresden,<br />

Germany, here with his wife, Ina, for three<br />

weeks, was fed up. “It feels like East Germany<br />

before the fall of the Berlin Wall,” he<br />

said. “There are all these rules, and none<br />

of them make any sense.”<br />

Mr. Franzke, 46, and his wife had been<br />

forced to stop climbing multiple times,<br />

threatened by park guards and told that<br />

the “Cuba Climbing” guidebook they were<br />

using to find routes in the valley was illegal<br />

to use because the authors do not live<br />

in Cuba.<br />

“It’s a real shame because it’s such a<br />

paradise,” Mr. Franzke said. The couple<br />

had climbed nearly every day they wished<br />

by evading the rules and the guards, but<br />

“we will never come back,” he said.<br />

This is the main worry for residents and<br />

climbers. Viñales is the hub of the valley<br />

and the heart of Viñales National Park.<br />

The bustling town has a population of<br />

By LYDIA POLGREEN<br />

JOHANNESBURG — It was exactly<br />

the kind of case the International Criminal<br />

Court was created to investigate: Yemen’s<br />

autocratic leader was clinging to<br />

power, turning his security forces’ guns<br />

on unarmed protesters.<br />

But when Yemen’s Nobel laureate,<br />

Tawakkol Karman, traveled to The Hague<br />

to ask prosecutors to investigate, she was<br />

told the court would first need the approval<br />

of the United Nations Security Council.<br />

That never happened, and today the former<br />

president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, is living<br />

comfortably in Yemen’s capital, still<br />

wielding influence.<br />

Now, as the world confronts evidence<br />

of atrocities in Syria as President Bashar<br />

al-Assad’s government battles a growing<br />

rebellion, there are signs that Mr. Assad,<br />

too, will evade prosecution.<br />

The men have not been prosecuted<br />

because they have powerful allies in the<br />

Security Council. That now threatens to<br />

undermine the still-fragile international<br />

consensus that formed the basis for the<br />

court’s creation in 2002: that leaders<br />

should be held accountable for crimes<br />

against their own people.<br />

Already, the failure to act against some<br />

Arab leaders has critics saying the court’s<br />

justice is reserved for outcast leaders, including<br />

an assortment from weak African<br />

states.<br />

“We have the feeling that international<br />

justice is not ruled by law,” said Rami Nakhla,<br />

an exiled Syrian activist. “It depends<br />

on the situation, it depends how valuable<br />

this person is. That is not real justice.”<br />

Yet the dream of a world court that could<br />

prosecute crimes against humanity is<br />

closer than ever to reality. Three former<br />

heads of state are in custody of international<br />

courts, and one, Charles Taylor, has<br />

been convicted. The International Criminal<br />

Court has convicted one defendant,<br />

Thomas Lubanga, a Congolese psychologist<br />

turned warlord who recruited child<br />

soldiers, and sentenced him to 14 years in<br />

prison. A former Bosnian Serb general,<br />

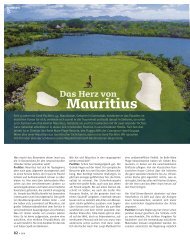

ALEX LOWTHER FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES<br />

Valle de Viñales, in Cuba. Climbing has been banned here since 2003.<br />

about 17,000 with more than 300 private<br />

boardinghouses that rent rooms to tourists.<br />

All that has allowed the valley to<br />

overcome the poverty typical across the<br />

country.<br />

Cuban climbers rely on tourists to donate<br />

shoes, harnesses and ropes to climb.<br />

Equipment is not available, and even if<br />

it were, it would cost too much in a country<br />

where government salaries average<br />

$15 to $25 a month. Without new donations,<br />

shoes, harnesses and ropes wear<br />

out. Without replacement, the bolts in the<br />

rock that secure climbers would corrode<br />

and eventually become unsafe. Climbing<br />

would become, essentially, impossible.<br />

Climbing was prohibited in 2003, four<br />

years after major climbing development<br />

started. The state deemed climbing a factor<br />

in peligrosidad, a vague designation of<br />

being dangerous to the state. It is an offense<br />

punishable by imprisonment. The climbing<br />

ban was never formally announced, nor<br />

was it enforced for tourists at all. For Cubans<br />

it was often a mere hassle, but consequences<br />

could be more severe. One veteran<br />

Cuban climber was put on notice of being<br />

considered peligroso in 2010, and several<br />

others were taken to the police station and<br />

had reports drawn up. This seems to have<br />

been more likely if the climbers were climbing<br />

and socializing with foreigners, which<br />

the state frowns upon.<br />

Since at least 2003, an explanation has<br />

been circulating that the government is<br />

Ratko Mladic, is appearing before a tribunal<br />

created to try accused war criminals<br />

from the former Yugoslavia.<br />

But the court can investigate crimes<br />

only in nations that have signed the Rome<br />

Statute, which created the court, unless<br />

the Security Council refers a case.<br />

“So many crimes have been committed<br />

here,” said Nabeel Rajab, a rights activist<br />

in Bahrain, where the royal family, with<br />

help from Saudi Arabia and the acquiescence<br />

of the United States, has used force<br />

to put down a pro-democracy uprising.<br />

“But because of the close relationship<br />

between Western powers and the government<br />

of Bahrain, how can we hope for<br />

justice?”<br />

busy organizing a system through which<br />

one would buy a daily pass or license to<br />

climb. No such pass yet exists.<br />

Many of the cliffs where climbing takes<br />

place are part of the national defense plan<br />

in case of attack, and climbers suspect<br />

that state security officials are worried<br />

that the Cubans and foreigners are there<br />

organizing against the government.<br />

Owners of casas particulares, as the<br />

private boardinghouses are called, said<br />

warnings about the rules were overblown.<br />

Oscar Jaime Rodriguez, owner of<br />

a boardinghouse that is the de facto base<br />

camp for climbers in the valley, sought to<br />

quiet fears. “They are always saying, ‘It’s<br />

prohibited, it’s prohibited,’ but climbers<br />

still come and they still climb,” he said.<br />

“It’s worth it.” (Since reporting there concluded<br />

at the end of March, climbers have<br />

said enforcement of the no climbing rule<br />

may have become more lenient.)<br />

On their last day in Cuba, after an unmolested<br />

climbing session in warm early<br />

morning sun and a “coco loco” cocktail<br />

in the shade, the Franzkes reconsidered<br />

their vow never to return.<br />

“Maybe all of the not so good stuff about<br />

Cuba will leave my memory,” Jens Franzke<br />

said. “I’ll just remember the beautiful<br />

people, the red soil, the salsa.” Mr. Franzke<br />

looked at the drink in his hand, smiled<br />

and said, “The coco loco.” He looked in the<br />

direction of the mogotes, and added, “And<br />

the spectacular climbing.”<br />

Uprisings Expose Global Court Flaws<br />

SAMUEL ARANDA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES<br />

Tawakkol Karman sought<br />

international justice for protesters<br />

killed in Yemen’s uprising.<br />

Powerful allies let<br />

officials elude justice<br />

in The Hague.<br />

The court has 120 member states, but<br />

three of the five veto-holding members of<br />

the Security Council — the United States,<br />

Russia and China — are not among them.<br />

Despite this, the court has turned into a<br />

touchstone for justice-seekers. The Security<br />

Council allowed the court to investigate<br />

Sudan’s president, Omar Hassan<br />

al-Bashir, who was indicted on charges<br />

of war crimes in Darfur, though the court<br />

has been unable to apprehend him.<br />

And in February 2011, the Security<br />

Council asked the International Criminal<br />

Court to investigate the Libyan government<br />

led by Colonel Muammar el-Qaddafi.<br />

The court handed down indictments<br />

against Colonel Qaddafi and several top<br />

officials, though he was killed in Libya before<br />

he could face prosecution.<br />

But the court has not taken action in<br />

any other Arab uprising, in no small part<br />

because of the ties between the countries<br />

involved and veto-holding members of<br />

the Security Council. Bahrain and Yemen<br />

are allies of the United States. Russia and<br />

China are close to Syria’s government.<br />

Debates have raged about whether<br />

the court, by closing off a graceful exit,<br />

makes dictators more likely to fight to the<br />

death.<br />

But supporters say the court has<br />

achieved more than expected. “The assumption<br />

was the court will take years to<br />

come into effect,” said Darryl Robinson,<br />

who worked as an adviser to the International<br />

Criminal Court’s prosecutor. “And<br />

once it is in force it is going to be this court<br />

with jurisdiction over Canada and Norway,<br />

with nothing to investigate.”<br />

Instead, much of the world has signed<br />

up, and protesters in Yemen, Bahrain,<br />

Libya and Syria have demanded that their<br />

leaders be sent to The Hague for trial. The<br />

deeper question is whether the failure to<br />

prosecute the autocrats of the Arab Spring<br />

will erode faith in the movement toward a<br />

system of international justice.<br />

Richard Dicker of Human Rights Watch<br />

said: “For justice to be legitimate, it is essential<br />

that it be applied equally to all.”<br />

world trends<br />

A Bruised Iceland Is Healing Nicely<br />

By SARAH LYALL<br />

REYKJAVIK, Iceland — For a country<br />

that four years ago plunged into a financial<br />

abyss so deep it all but shut down overnight,<br />

Iceland seems to be doing surprisingly<br />

well.<br />

It has repaid, early, many of the international<br />

loans that kept it afloat. Unemployment<br />

is hovering around 6 percent, and falling.<br />

And while much of Europe is struggling<br />

to pull itself out of the recessionary swamp,<br />

Iceland’s economy is expected to grow by<br />

2.8 percent this year.<br />

“Everything has turned around,” said<br />

Adalheidur Hedinsdottir, who owns the<br />

coffee chain Kaffitar, and has plans to open<br />

a new cafe and bakery. “When we told the<br />

bank we wanted to make a new company,<br />

they said, ‘Do you want to borrow money?’ ”<br />

she went on. “We haven’t been hearing that<br />

for a while.”<br />

Analysts cite the surprising turn of<br />

events to a combination of fortuitous decisions<br />

and good luck, and caution that the<br />

lessons of Iceland’s turnaround are not<br />

readily applicable to the larger and more<br />

complex economies of Europe.<br />

But during the crisis, the country did<br />

many things different from its European<br />

counterparts. It let its three largest banks<br />

fail, instead of bailing them out. It ensured<br />

that domestic depositors got their money<br />

back and gave debt relief to struggling homeowners<br />

and to businesses facing bankruptcy.<br />

“Taking down a company with positive<br />

cash flow but negative equity would in the<br />

given circumstances have a domino effect,<br />

causing otherwise sound companies to<br />

collapse,” said Thorolfur Matthiasson, an<br />

economics professor at the University of<br />

Iceland. “Forgiving debt under those circumstances<br />

can be profitable for the financial<br />

institutions and help the economy and<br />

reduce unemployment as well.”<br />

Iceland also had some advantages when<br />

it entered the crisis: relatively few government<br />

debts, a strong social safety net and a<br />

fluctuating currency whose rapid devaluation<br />

in 2008 caused pain for consumers<br />

but helped buoy the all-important export<br />

market. Government officials, who at the<br />

height of the crisis were reduced to begging<br />

for help from places like the Faroe Islands,<br />

are now cautiously bullish.<br />

“We’re in a very comfortable place because<br />

the government has been very stable<br />

in fiscal terms and is making good progress<br />

in balancing its books,” said Gudmundur<br />

Arnason, the Finance Ministry’s permanent<br />

secretary. “We are self-reliant and can<br />

borrow on our own without having to rely<br />

on the good will of our Nordic neighbors”<br />

or lenders like the International Monetary<br />

Fund.<br />

But not even Mr. Arnason says he believes<br />

that all is perfect. Inflation, which<br />

reached nearly 20 percent during the crisis,<br />

is still running at 5.4 percent, and even with<br />

the government’s relief programs, most of<br />

the country’s homeowners remain awash<br />

in debt, weighed down by inflation-indexed<br />

mortgages in which the principal, disastrously,<br />

rises with the inflation rate. Taxes<br />

are high. And with the country’s currency,<br />

the krona, worth between about 40 and 75<br />

percent of its pre-2008 value, imports are<br />

punishingly expensive.<br />

Strict currency controls, imposed during<br />

Good decisions and luck<br />

speed a return from the<br />

financial abyss.<br />

the crisis, mean that Icelandic companies<br />

are forbidden to invest abroad.<br />

At the same time, foreigners are forbidden<br />

to take their money out of the country<br />

— a situation that has tied up foreign investments<br />

worth, according to various estimates,<br />

between $3.4 billion and $8 billion.<br />

“The capital controls are worse and<br />

worse for companies, but the fear is that if<br />

we lift them, the value of the krona will collapse,”<br />

Professor Matthiasson said.<br />

He said the only solution would be for Iceland<br />

to dispense with the krona and join a<br />

larger, more stable currency. The choices<br />

at the moment seem to be the euro, which is<br />

having its own difficulties,<br />

and the Canadian<br />

dollar.<br />

Not everyone buys<br />

into the rosy picture<br />

presented by officialdom.<br />

Jon Danielsson,<br />

an Icelander who<br />

teaches global finance<br />

at the London School of<br />

Economics, said that<br />

both the International Monetary Fund,<br />

which bailed Iceland out during the crisis,<br />

and the government had a vested interest in<br />

painting a positive picture of the situation.<br />

Some Icelanders say they have been<br />

soothed by the country’s bold decision to<br />

initiate an extensive criminal investigation<br />

into the financial debacle.<br />

A visit to Iceland late last month revealed<br />

a far different place from the shellshocked<br />

nation of 2008. Stores and hotels were full.<br />

The Harpa, a glass-and-steel concert hall<br />

and conference center designed in part by<br />

the artist Olafur Eliasson and opened in<br />

2011, soared over the Reykjavik skyline,<br />

next to a huge construction site that is to<br />

house a luxury waterside hotel. Employers<br />

said that instead of having to lay off workers,<br />

they were in some cases having trouble<br />

finding people to hire.<br />

Icelanders said that they had stopped<br />

feeling ashamed and isolated, the way that<br />

they did during the worst of the crisis, when<br />

their country was portrayed as a greedy<br />

and foolish pariah state and its British assets<br />

were frozen by the British government<br />

using the blunt and humiliating instrument<br />

of antiterror legislation.<br />

“We went through this complicated and<br />

terrible experience and were in the center<br />

of world events,” said Kristrun Heimisdottir,<br />

a lecturer in law and jurisprudence at<br />

the University of Akureyri in northern Iceland.<br />

She compared Iceland’s shame to that of<br />

a private person thrust onto the front pages<br />

by a lurid scandal. “It might take 20 years<br />

to recover from the stress and humiliation<br />

of having their personal life paraded before<br />

the world,” she said. “But it turned out that<br />

what happened to us was a microcosm of<br />

the whole crisis.”<br />

ANDREW TESTA FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES<br />

After its free fall,<br />

Iceland’s economy<br />

is expected to<br />

grow 2.8 percent<br />

this year. Window<br />

shoppers strolling in<br />

Reykjavik.