Genomic Imprinting and Uniparental Disomy 531 • Confined placental mosaicism (CPM) (see Chapter 12) with a trisomic cell line for chromosomes 6, 7, 11, 14, or 15 (and possibly also 16) found in chorionic villus sampling but only normal cells in amniotic fluid • <strong>The</strong> presence <strong>of</strong> a supernumerary marker chromosome originating from one <strong>of</strong> these chromosomes • De novo or familial Robertsonian translocations (see Chapters 3 and 9) involving chromosomes 14 or 15, especially when homologous • Abnormal prenatal ultrasound findings <strong>of</strong> features seen in known UPD syndromes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to Dr. David Wang for preparation <strong>of</strong> the diagrams. I also thank Jo Ann Rieger for her assistance with preparation <strong>of</strong> the manuscript. REFERENCES 1. Crouse, H.V. (1960) <strong>The</strong> controlling element in sex chromosome behaviour in Sciara. Genetics 45, 1429–1443. 2. Hall, J.G. (1990) Genomic imprinting: review and relevance to human diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 46, 857–873. 3. Hoppe, P.C. and Illmensee, K. (1977) Microsurgically produced homozygous-diploid uniparental mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74, 5657–5661. 4. McGrath, J. and Solter, D. (1984) Completion <strong>of</strong> mouse embryogenesis requires both the maternal and paternal genomes. Cell 37, 179–183. 5. Surani, M.A.H., Barton, S.C., and Norris, M.L. (1984) Development <strong>of</strong> reconstituted mouse eggs suggests imprinting <strong>of</strong> the genome during gametogenesis. Nature 308, 548–550. 6. Barton, S.C., Surani, M.A.H., and Norris, M.L. (1984) Role <strong>of</strong> paternal and maternal genomes in mouse development. Nature 311, 374–376. 7. Surani, M.A.H., Barton, S.C., and Norris, M.L. (1986) Nuclear transplantation in the mouse: heritable differences between parental genomes after activation <strong>of</strong> the embryonic genome. Cell 45, 127–136. 8. Linder, D., McCaw, B.K., and Hecht, F. (1975) Parthenogenic origin <strong>of</strong> benign ovarian teratomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 292, 63–66. 9. Kajii, T. and Ohama, K. (1977) Androgenetic origin <strong>of</strong> hydatidiform mole. Nature 268, 633–634. 10. Lawler, S.D., Povey, S., Fisher, R.A., and Pickthal, V.J. (1982) Genetic studies on hydatidiform moles. II. <strong>The</strong> origin <strong>of</strong> complete moles. Ann. Hum. Genet. 46, 209–222. 11. McFadden, D.E. and Kalousek, D.K. (1991) Two different phenotypes <strong>of</strong> fetuses with chromosomal triploidy: correlation with parental origin <strong>of</strong> the extra haploid set. Am. J. Med. Genet. 38, 535–538. 12. Jacobs, P.A., Szulman, A.E., Funkhouser, J., Matsuura, J.S., and Wilson, C.C. (1982) Human triploidy: relationship between parental origin <strong>of</strong> the additional haploid complement and development <strong>of</strong> partial hydatidiform mole. Ann. Hum. Genet. 46, 223–231. 13. McFadden, D.E., Kwong, L.C., Yam, I.Y., and Langlois, S. (1993) Parental origin <strong>of</strong> triploidy in human fetuses: evidence for genomic imprinting. Hum. Genet. 92, 465–469. 14. Cattanach, B.M. (1986) Parental origin effects in mice. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 97(Suppl.), 137–150. 15. Lyon, M.F. (1988) <strong>The</strong> William Allan Memorial award address: X-chromosome inactivation and the location and expression <strong>of</strong> X-linked genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 42, 8–16. 16. Sharman, G.B. (1971) Late DNA replication in the paternally derived X chromosome <strong>of</strong> female kangaroos. Nature 230, 231–232. 17. Takagi, N. and Sasaki, M. (1975) Preferential inactivation <strong>of</strong> the paternally derived X chromosome in the extraembryonic membranes <strong>of</strong> the mouse. Nature 256, 640–642. 18. West, J.D., Freis, W.I., Chapman, V.M., and Papaioannou, V.E. (1977) Preferential expression <strong>of</strong> the maternally derived X chromosome in the mouse yolk sac. Cell 12, 873–882. 19. Harper, M.I., Fosten, M., and Monk, M. (1982) Preferential paternal X inactivation in extra-embryonic tissues <strong>of</strong> early mouse embryos. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 67, 127–138. 20. Harrison, K.B. (1989) X-chromosome inactivation in the human cytotrophoblast. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 52, 37–41. 21. Goto, T., Wright, E., and Monk, M. (1997) Paternal X-chromosome inactivation in human trophoblastic cells. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 3, 77–80. 22. Migeon, B.R., Wolf, S.F., Axelman, J., Kaslow, D.C., and Schmidt, M. (1985) Incomplete X chromosome dosage compensation in chorionic villi <strong>of</strong> human placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 3390–3394. 23. Mohandas, T.K., Passage, M.B., Williams, J.W.R., Sparks, R.S., Yen, P.H., and Shapiro, L.J. (1989) X-chromosome inactivation in cultured cells from human chorionic villi. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 15, 131–136. 24. Looijenga, L.H.J., Gillis, A.J.M., Verkerk, A.J.M.H., van Lutten, W.L.J., and Ooserhuis, J.W. (1999) Heterogeneous X inactivation in trophoblastic cells <strong>of</strong> human full-term female placentas. Am. J. Hum. Genet 64, 1445–1452.

532 Jin-Chen Wang 25. Ledbetter, D.H. and Engel, E. (1995) Uniparental disomy in humans: development <strong>of</strong> an imprinting map and its implications for prenatal diagnosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 4, 1757–1764. 26. Barlow, D.P. (1995) Gametic Imprinting in mammals. Science 270, 1610–1613. 27. Morison, I.M. and Reeve, A.E. (1998) A catalogue <strong>of</strong> imprinted genes and parent-<strong>of</strong>-origin effects in humans and animals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 1610–1613. 28. Monk, M. (1988) Genomic imprinting. Genes Dev. 2, 921–925. 29. Razin, A. and Cedar, H. ( 1994) DNA methylation and genomic imprinting. Cell 77, 473–476. 30. Mohandas, T., Sparkes, R.S., and Shapiro, L.J. (1981) Reactivation <strong>of</strong> an inactive human X-chromosome: evidence for inactivation by DNA methylation. Science 211, 393–396. 31. Yen, P.H., Patel, P., Chinault, A.C., Mohandas, T., and Shapiro, L.J. (1984) Differential methylation <strong>of</strong> hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase genes on active and inactive human X chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 1759–1763. 32. Keshet, I., Lieman-Hurwitz, J., and Cedar, H. (1986) DNA methylation affects the formation <strong>of</strong> active chromatin. Cell 44, 535–543. 33. Reik, W., Collick, A., Norris, M.L., Barton, S.C., and Surani, M.A. (1987) Genomic imprinting determines methylation <strong>of</strong> parental alleles in transgenic mice. Nature 328, 248–251. 34. Sapienza, C. Peterson, A.C., Rossant, J., and Balling, R. (1987) Degree <strong>of</strong> methylation <strong>of</strong> transgenes is dependent on gamete <strong>of</strong> origin. Nature 328, 251–254. 35. Swain, J.L., Stewart, T.A., and Leder, P. (1987) Parental legacy determines methylation and expression <strong>of</strong> an autosomal transgene: a molecular mechanism for parental imprinting. Cell 50, 719–727. 36. Bartolomei, M., Zemel, S., and Tilghman, S.M. (1991) Parental imprinting <strong>of</strong> the mouse H19 gene. Nature 351, 153–155. 37. Ferguson-Smith, A.C., Sasaki, H., Cattanach, B.M., and Surani, M.A. (1993) Parental-origin-specific epigenetic modification <strong>of</strong> the mouse H19 gene. Nature 362, 751–775 38. Li, E., Beard, C., and Jaenisch, R. (1993) Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature 366, 362–365. 39. DeChiara, T.M., Robertson, E.J., and Efstratiadis, A. (1991) Parental imprinting <strong>of</strong> the mouse insulin-like growth factor II gene. Cell 64, 849–859. 40. Sasaki, H., Jones, P.A., Chaillet, J.R., et al. (1992) Parental imprinting: potentially active chromatin <strong>of</strong> the repressed maternal allele <strong>of</strong> the mouse insulin-like growth factor II (Igf2) gene. Genes Dev. 6, 1843–1856. 41. Bell, A.C. and Felsenfeld, G. (2000) Methuylation <strong>of</strong> a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression <strong>of</strong> the Igf2 gene. Nature 405, 482–485. 42. Hark, A.T., Schoenherr, C.J., Katz, D.J., Ingram, R.S., Levorse, J.M., and Tilghman, S.M. (2000) CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature 405, 486–489. 43. Barlow, D.P., Stöger, R., Herrmann, B.G., Saito, K., and Schweifer, N. (1991) <strong>The</strong> mouse insulin-like growth factor type-2 receptor is imprinted and closely linked to the Tme locus. Nature 349, 84–87. 44. Stöger, R., Kubicka, P., Liu, C.G., et al. (1993) Maternal-specific methylation <strong>of</strong> the imprinted mouse Igf2r locus identifies the expressed locus as carrying the imprinting signal. Cell 73, 61–71. 45. Driscoll, D.J., Waters, M.F., Williams, C.A., et al. (1992) A DNA methylation imprint, determined by the sex <strong>of</strong> the parent, distinguishes the Angelman and Prader–Willi syndromes. Genomics 13, 917–924. 46. Mowery-Rushton, P.A., Driscoll, D.J., Nicholls, R.D., Locker, J., and Surti, U. (1996) DNA methylation patterns in human tissues <strong>of</strong> uniparental origin using a zinc-finger gene (ZNF127) from the Angelman/Prader–Willi region. Am. J. Med. Genet. 61, 140–146. 47. Glenn, C.C., Porter, K.A., Jong, M.T., Nicholls, R.D., and Driscoll, D.J. (1993) Functional imprinting and epigenetic modification <strong>of</strong> the human SNRPN gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2, 2001–2005. 48. Glenn, C.C., Saitoh, S., Jong, M.T.C., Filbrandt, M.M., Surti, U., Driscoll, D.J., and Nicholls, R.D. (1996) Gene structure, DNA methylation, and imprinted expression <strong>of</strong> the human SNRPN gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 58, 335–346. 49. Dittrich, B., Buiting, K., Gross, S., and Horsthemke, B. (1993) Characterization <strong>of</strong> a methylation imprint in the Prader– Willi syndrome chromosome region. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2, 1995–1999. 50. Zhang, Y., Shields, T., Crenshaw, T., Hao, Y., Moulton, T., and Tycko, B. (1993) Imprinting <strong>of</strong> human H19: allelespecific CpG methylation, loss <strong>of</strong> the active allele in Wilms tumor, and potential for somatic allele switching. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 53, 113–124. 51. Schneid, H., Seurin, D., Vazquez, M-P., Gourmelen, M., Cabrol, S., and Bouc, Y.L. (1993) Parental allele specific methylation <strong>of</strong> the human insulin-like growth factor II gene and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 30, 353–362. 52. Ohlsson, R., Nyström, A., Pfeifer-Ohlsson, S., et al. (1993) IGF2 is parentally imprinted during human embryogenesis and in the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Nature Genet. 4, 94–97. 53. Kalscheuer, V.M., Mariman, E.C., Schepens, M.T., Rehder, H., and Ropers, H-H. (1993) <strong>The</strong> insulin-like growth factor type-2 receptor gene is imprinted in the mouse but not in humans. Nature Genet. 5, 74–78. 54. Kitsberg, D., Selig, S., Brandeis, M., et al. (1993) Allele-specific replication timing <strong>of</strong> imprinted gene regions. Nature 364, 459–463. 55. Knoll, J.H.M., Cheng, S-D., and Lalande, M. (1994) Allele specificity <strong>of</strong> DNA replication timing in the Angelman/ Prader–Willi syndrome imprinted chromosomal region. Nature Genet. 6, 41–46.

- Page 1 and 2:

The Principles of Clinical Cytogene

- Page 4 and 5:

The Principles of Clinical Cytogene

- Page 6 and 7:

v Preface In the summer of 1989, on

- Page 8 and 9:

vii Preface to First Edition The st

- Page 10 and 11:

ix Contents Preface ...............

- Page 12:

Contributors SARAH HUTCHINGS CLARK,

- Page 16:

History of Clinical Cytogenetics 1

- Page 19 and 20:

4 Steven Gersen The hypotonic solut

- Page 21 and 22:

6 Steven Gersen marrow aspiration,

- Page 23 and 24:

8 Steven Gersen 9. Hsu, T.C. (1952)

- Page 25 and 26:

10 Martha Keagle Fig. 1. DNA struct

- Page 27 and 28:

12 Martha Keagle Fig. 3. Transcript

- Page 29 and 30:

14 Martha Keagle Fig. 5. Translatio

- Page 31 and 32:

16 Martha Keagle Fig. 7. The levels

- Page 33 and 34:

18 Martha Keagle single-copy DNA is

- Page 35 and 36:

20 Martha Keagle Fig. 10. Mitosis.

- Page 37 and 38:

22 Martha Keagle Fig. 11. Schematic

- Page 39 and 40:

24 Martha Keagle Fig. 13. Spermatog

- Page 42 and 43:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 27 IN

- Page 44 and 45:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 29 Fi

- Page 46 and 47:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 31 Fi

- Page 48 and 49:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 33 Ta

- Page 50 and 51:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 35 Fi

- Page 52 and 53:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 37 Fi

- Page 54 and 55:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 39 Fi

- Page 56 and 57:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 41 Fi

- Page 58 and 59:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 43 Fi

- Page 60 and 61:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 45 Fi

- Page 62 and 63:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 47 In

- Page 64 and 65:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 49 Ma

- Page 66 and 67:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 51 Un

- Page 68 and 69:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 53 Ta

- Page 70 and 71:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 55 46

- Page 72 and 73:

Human Chromosome Nomenclature 57 nu

- Page 74:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 59 II E

- Page 78 and 79:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 63 INTR

- Page 80 and 81:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 65 amni

- Page 82 and 83:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 67 Prep

- Page 84 and 85:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 69 Fig.

- Page 86 and 87:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 71 Fig.

- Page 88 and 89:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 73 Fig.

- Page 90 and 91:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 75 Fig.

- Page 92 and 93:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 77 Lack

- Page 94:

Basic Laboratory Procedures 79 Once

- Page 97 and 98:

82 Christopher McAleer Fig. 1. Sche

- Page 99 and 100:

84 Christopher McAleer measurements

- Page 101 and 102:

86 Christopher McAleer allow light

- Page 103 and 104:

88 Christopher McAleer High-dry obj

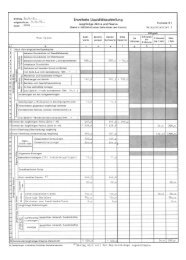

- Page 105 and 106:

90 Christopher McAleer Fig. 3. Sche

- Page 108 and 109:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 110 and 111:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 112 and 113:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 114 and 115:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 116 and 117:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 118 and 119:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 120 and 121:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 122 and 123:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 124 and 125:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 126 and 127:

Quality Control and Quality Assuran

- Page 128 and 129:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 130 and 131:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 132 and 133:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 134 and 135:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 136 and 137:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 138 and 139:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 140 and 141:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 142 and 143:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 144 and 145:

Automation in the Cytogenetics Labo

- Page 146 and 147:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 131 III Clinic

- Page 148 and 149:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 133 INTRODUCTI

- Page 150 and 151:

135 Table 1 Parental and Meiotic/Mi

- Page 152 and 153:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 137 Fig. 2. Sc

- Page 154 and 155:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 139 forming ab

- Page 156 and 157:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 141 Fig. 5. Th

- Page 158 and 159:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 143 Fig. 6. Pr

- Page 160 and 161:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 145 Fig. 8. An

- Page 162 and 163:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 147 trisomies,

- Page 164 and 165:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 149 21 and ind

- Page 166 and 167:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 151 molecular

- Page 168 and 169:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 153 Fig. 10. T

- Page 170 and 171:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 155 This marke

- Page 172 and 173:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 157 47. Hawley

- Page 174 and 175:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 159 110. Lindo

- Page 176 and 177:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 161 171. Moghe

- Page 178 and 179:

Autosomal Aneuploidy 163 231. Reese

- Page 180 and 181:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 182 and 183:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 184 and 185:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 186 and 187:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 188 and 189:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 190 and 191:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 192 and 193:

177 Prader-Willi Paternal deletion

- Page 194 and 195:

179 Table 2 Some Recurring Duplicat

- Page 196 and 197:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 198 and 199:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 200 and 201:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 202 and 203:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 204 and 205:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 206 and 207:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 208 and 209:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 210 and 211:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 212 and 213:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 214 and 215:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 216 and 217:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 218 and 219:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 220 and 221:

Structural Chromosome Rearrangement

- Page 222 and 223:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 224 and 225:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 226 and 227:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 228 and 229:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 230 and 231:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 232 and 233:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 234 and 235:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 236 and 237:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 238 and 239:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 240 and 241:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 242 and 243:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 244 and 245:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 246 and 247:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 248 and 249:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 250 and 251:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 252 and 253:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 254 and 255:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 256 and 257:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 258 and 259:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 260 and 261:

Sex Chromosomes and Sex Chromosome

- Page 262 and 263:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 247 INT

- Page 264 and 265:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 249 Amo

- Page 266 and 267:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 251 Tab

- Page 268 and 269:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 253 gen

- Page 270 and 271:

255 Primary ciliary dyskinesia Auto

- Page 272 and 273:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 257 cha

- Page 274 and 275:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 259 Tab

- Page 276 and 277:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 261 Fig

- Page 278 and 279:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 263 rat

- Page 280:

Cytogenetics of Infertility 265 39.

- Page 283 and 284:

268 Linda Marie Randolph By 1986, m

- Page 285 and 286:

270 Linda Marie Randolph Table 1 Ch

- Page 287 and 288:

272 Linda Marie Randolph Table 4 Th

- Page 289 and 290:

274 Linda Marie Randolph Table 6 Fr

- Page 291 and 292:

276 Linda Marie Randolph rate of 14

- Page 293 and 294:

278 Table 8 Outcome in Early (11-14

- Page 295 and 296:

280 Linda Marie Randolph Table 9 Vo

- Page 297 and 298:

282 Linda Marie Randolph In 1995, O

- Page 299 and 300:

284 Linda Marie Randolph Fig. 1. Il

- Page 301 and 302:

286 Linda Marie Randolph reported c

- Page 303 and 304:

288 Linda Marie Randolph The underl

- Page 305 and 306:

290 Linda Marie Randolph Fig. 3. Ul

- Page 307 and 308:

292 Linda Marie Randolph Fig. 4. Ul

- Page 309 and 310:

294 Linda Marie Randolph Fig. 5. Ul

- Page 311 and 312:

296 Linda Marie Randolph Fig. 6. De

- Page 313 and 314:

298 Linda Marie Randolph Choroid Pl

- Page 315 and 316:

300 Linda Marie Randolph Table 13 C

- Page 317 and 318:

302 Linda Marie Randolph Table 14 U

- Page 319 and 320:

304 Linda Marie Randolph then that

- Page 321 and 322:

306 Table 15 Prenatal Results for R

- Page 323 and 324:

308 Linda Marie Randolph Table 17 O

- Page 325 and 326:

310 Linda Marie Randolph DNA marker

- Page 327 and 328:

312 Linda Marie Randolph XX and XY

- Page 329 and 330:

314 Linda Marie Randolph 54. Simpso

- Page 331 and 332:

316 Linda Marie Randolph 116. Wang,

- Page 333 and 334:

318 Linda Marie Randolph 173. Cicer

- Page 335 and 336:

320 Linda Marie Randolph 232. Benn,

- Page 338 and 339:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 340 and 341:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 342 and 343:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 344 and 345:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 346 and 347:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 348 and 349:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 350 and 351:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 352 and 353:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 354 and 355:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 356 and 357:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 358 and 359:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 360:

Cytogenetics of Spontaneous Abortio

- Page 363 and 364:

348 Xiao-Xiang Zhang Fig. 1. An exa

- Page 365 and 366:

350 Xiao-Xiang Zhang cases availabl

- Page 367 and 368:

352 Xiao-Xiang Zhang Fig. 2. Metaph

- Page 369 and 370:

354 Xiao-Xiang Zhang patients, grea

- Page 371 and 372:

356 Xiao-Xiang Zhang Fig. 5. G-Band

- Page 373 and 374:

358 Xiao-Xiang Zhang Fig. 7. Sister

- Page 375 and 376:

360 Xiao-Xiang Zhang REFERENCES 1.

- Page 378 and 379:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 380 and 381:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 382 and 383:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 384 and 385:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 386 and 387:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 388 and 389:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 390 and 391:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 392 and 393:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 394 and 395:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 396 and 397:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 398 and 399:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 400 and 401:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 402 and 403:

387 Table 5 Association of Recurren

- Page 404 and 405:

389 del(8)(q22) t(8;16)(p11.2;p13)

- Page 406 and 407:

391 +17 -17 2° assoc. with +21 i(1

- Page 408 and 409:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 410 and 411:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 412 and 413:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 414 and 415:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 416 and 417:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 418 and 419:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 420 and 421:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 422 and 423:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 424 and 425:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 426 and 427:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 428 and 429:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 430 and 431:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 432 and 433:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 434 and 435:

Cytogenetics of Hematologic Neoplas

- Page 436 and 437:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 421 IN

- Page 438 and 439:

423 Aytpical (see well-differentiat

- Page 440 and 441:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 425 So

- Page 442 and 443:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 427 ca

- Page 444 and 445:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 429 do

- Page 446 and 447:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 431 cl

- Page 448 and 449:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 433 Fi

- Page 450 and 451:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 435 Fi

- Page 452 and 453:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 437 Fi

- Page 454 and 455:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 439 no

- Page 456 and 457:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 441 ch

- Page 458 and 459:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 443 Fi

- Page 460 and 461:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 445 8.

- Page 462 and 463:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 447 64

- Page 464 and 465:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 449 11

- Page 466:

Cytogenetics of Solid Tumors 451 17

- Page 469 and 470:

454 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 471 and 472:

456 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 473 and 474:

458 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 475 and 476:

460 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 477 and 478:

462 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 479 and 480:

464 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 481 and 482:

466 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 483 and 484:

468 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 485 and 486:

470 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 487 and 488:

472 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 489 and 490:

474 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 491 and 492:

476 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 493 and 494:

478 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 495 and 496: 480 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 497 and 498: 482 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 499 and 500: 484 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 501 and 502: 486 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 503 and 504: 488 Daynna Wolff and Stuart Schwart

- Page 506: Fragile X 491 VI Beyond Chromosomes

- Page 510 and 511: Fragile X 495 18 Fragile X From Cyt

- Page 512 and 513: Fragile X 497 Fig. 1. Appearance of

- Page 514 and 515: Fragile X 499 Table 4 Characteristi

- Page 516 and 517: Fragile X 501 (KH domains) and clus

- Page 518 and 519: Fragile X 503 have suggested differ

- Page 520 and 521: Fragile X 505 The premutation form

- Page 522 and 523: Fragile X 507 Table 4). FRAXE expan

- Page 524 and 525: Fragile X 509 35. Heitz, D., Devys,

- Page 526 and 527: Fragile X 511 93. Bennetto, L. and

- Page 528: Fragile X 513 147. Oostra, B.A. and

- Page 531 and 532: 516 Jin-Chen Wang Fig. 1. Diagramma

- Page 533 and 534: 518 Jin-Chen Wang (50) and IGF2 (pa

- Page 535 and 536: 520 Jin-Chen Wang 3. Imprinting cer

- Page 537 and 538: 522 Jin-Chen Wang UNIPARENTAL DISOM

- Page 539 and 540: 524 Jin-Chen Wang Fig. 3. A diagram

- Page 541 and 542: 526 Jin-Chen Wang cause SRS (183).

- Page 543 and 544: 528 Jin-Chen Wang Studies comparing

- Page 545: 530 Jin-Chen Wang upd(21)pat Two ca

- Page 549 and 550: 534 Jin-Chen Wang 84. Bürger, J.,

- Page 551 and 552: 536 Jin-Chen Wang 138. Dryja, T.P.,

- Page 553 and 554: 538 Jin-Chen Wang 192. Karanjawala,

- Page 555 and 556: 540 Jin-Chen Wang 248. Creau-Goldbe

- Page 557 and 558: 542 Sarah Hutchings Clark condition

- Page 559 and 560: 544 Sarah Hutchings Clark the couns

- Page 561 and 562: 546 Sarah Hutchings Clark the coupl

- Page 563 and 564: 548 Sarah Hutchings Clark chromosom

- Page 565 and 566: 550 Sarah Hutchings Clark SMITH-MAG

- Page 567 and 568: 552 Sarah Hutchings Clark often at

- Page 569 and 570: 554 Sarah Hutchings Clark The relat

- Page 571 and 572: 556 Sarah Hutchings Clark Although,

- Page 573 and 574: 558 Sarah Hutchings Clark 33. Nicol

- Page 575 and 576: 560 Index Abnormalities, order of,

- Page 577 and 578: 562 Index Anus, imperforate, 310 AP

- Page 579 and 580: 564 Index CDK4, 394 CDK6, 396 CDKN2

- Page 581 and 582: 566 Index mosaicism, in amniotic fl

- Page 583 and 584: 568 Index Cutaneous anaplastic larg

- Page 585 and 586: 570 Index proximal 15q, 178, t179 p

- Page 587 and 588: 572 Index Folic acid pathway, 75 Fo

- Page 589 and 590: 574 Index Hereditary neuropathy wit

- Page 591 and 592: 576 Index Intrachromosomal recombin

- Page 593 and 594: 578 Index Male-specific region, Y c

- Page 595 and 596: 580 Index MTX, 76 Mucosa-associated

- Page 597 and 598:

582 Index Octamer, 14 Okazaki fragm

- Page 599 and 600:

584 Index Premature separation of s

- Page 601 and 602:

586 Index Recombinant chromosomes n

- Page 603 and 604:

588 Index Sézary syndrome (SS), t3

- Page 605 and 606:

590 Index t(4;14), 475 t(5;10), 375

- Page 607 and 608:

592 Index Treacher Collins syndrome

- Page 609 and 610:

594 Index Xq deletions, 225 Y trans

- Page 611 and 612:

596 Index XX males, 467, f468 and a