3rd Missionary Trip - Lorin

3rd Missionary Trip - Lorin

3rd Missionary Trip - Lorin

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

συνηγμένοι. 9 καθεζόμενος δέ τις νεανίας ὀνόματι Εὔτυχος ἐπὶ<br />

τῆς θυρίδος, καταφερόμενος ὕπνῳ βαθεῖ διαλεγομένου τοῦ<br />

Παύλου ἐπὶ πλεῖον, κατενεχθεὶς ἀπὸ τοῦ ὕπνου ἔπεσεν ἀπὸ<br />

τοῦ τριστέγου κάτω καὶ ἤρθη νεκρός. 10 καταβὰς δὲ ὁ Παῦλος<br />

ἐπέπεσεν αὐτῷ καὶ συμπεριλαβὼν εἶπεν· μὴ θορυβεῖσθε, ἡ<br />

γὰρ ψυχὴ αὐτοῦ ἐν αὐτῷ ἐστιν. 11 ἀναβὰς δὲ καὶ κλάσας τὸν<br />

ἄρτον καὶ γευσάμενος ἐφʼ ἱκανόν τε ὁμιλήσας ἄχρι αὐγῆς, οὕτως<br />

ἐξῆλθεν. 12 ἤγαγον δὲ τὸν παῖδα ζῶντα καὶ παρεκλήθησαν οὐ<br />

μετρίως.<br />

7 On the first day of the week, when we met to break bread,<br />

Paul was holding a discussion with them; since he intended<br />

to leave the next day, he continued speaking until midnight. 8<br />

There were many lamps in the room upstairs where we were<br />

meeting. 9 A young man named Eutychus, who was sitting in<br />

the window, began to sink off into a deep sleep while Paul talked<br />

still longer. Overcome by sleep, he fell to the ground three floors<br />

below and was picked up dead. 10 But Paul went down, and<br />

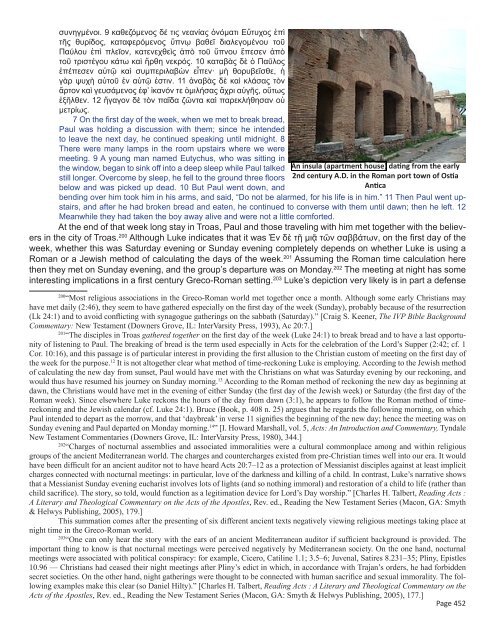

An insula (apartment house) dating from the early<br />

2nd century A.D. in the Roman port town of Ostia<br />

Antica<br />

bending over him took him in his arms, and said, “Do not be alarmed, for his life is in him.” 11 Then Paul went upstairs,<br />

and after he had broken bread and eaten, he continued to converse with them until dawn; then he left. 12<br />

Meanwhile they had taken the boy away alive and were not a little comforted.<br />

At the end of that week long stay in Troas, Paul and those traveling with him met together with the believers<br />

in the city of Troas. 200 Although Luke indicates that it was Ἐν δὲ τῇ μιᾷ τῶν σαββάτων, on the first day of the<br />

week, whether this was Saturday evening or Sunday evening completely depends on whether Luke is using a<br />

Roman or a Jewish method of calculating the days of the week. 201 Assuming the Roman time calculation here<br />

then they met on Sunday evening, and the group’s departure was on Monday. 202 The meeting at night has some<br />

interesting implications in a first century Greco-Roman setting. 203 Luke’s depiction very likely is in part a defense<br />

200 “Most religious associations in the Greco-Roman world met together once a month. Although some early Christians may<br />

have met daily (2:46), they seem to have gathered especially on the first day of the week (Sunday), probably because of the resurrection<br />

(Lk 24:1) and to avoid conflicting with synagogue gatherings on the sabbath (Saturday).” [Craig S. Keener, The IVP Bible Background<br />

Commentary: New Testament (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), Ac 20:7.]<br />

201 “The disciples in Troas gathered together on the first day of the week (Luke 24:1) to break bread and to have a last opportunity<br />

of listening to Paul. The breaking of bread is the term used especially in Acts for the celebration of the Lord’s Supper (2:42; cf. 1<br />

Cor. 10:16), and this passage is of particular interest in providing the first allusion to the Christian custom of meeting on the first day of<br />

the week for the purpose.<br />

Page 452<br />

12 It is not altogether clear what method of time-reckoning Luke is employing. According to the Jewish method<br />

of calculating the new day from sunset, Paul would have met with the Christians on what was Saturday evening by our reckoning, and<br />

would thus have resumed his journey on Sunday morning. 13 According to the Roman method of reckoning the new day as beginning at<br />

dawn, the Christians would have met in the evening of either Sunday (the first day of the Jewish week) or Saturday (the first day of the<br />

Roman week). Since elsewhere Luke reckons the hours of the day from dawn (3:1), he appears to follow the Roman method of timereckoning<br />

and the Jewish calendar (cf. Luke 24:1). Bruce (Book, p. 408 n. 25) argues that he regards the following morning, on which<br />

Paul intended to depart as the morrow, and that ‘daybreak’ in verse 11 signifies the beginning of the new day; hence the meeting was on<br />

Sunday evening and Paul departed on Monday morning. 14 ” [I. Howard Marshall, vol. 5, Acts: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale<br />

New Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1980), 344.]<br />

202 “Charges of nocturnal assemblies and associated immoralities were a cultural commonplace among and within religious<br />

groups of the ancient Mediterranean world. The charges and countercharges existed from pre-Christian times well into our era. It would<br />

have been difficult for an ancient auditor not to have heard Acts 20:7–12 as a protection of Messianist disciples against at least implicit<br />

charges connected with nocturnal meetings: in particular, love of the darkness and killing of a child. In contrast, Luke’s narrative shows<br />

that a Messianist Sunday evening eucharist involves lots of lights (and so nothing immoral) and restoration of a child to life (rather than<br />

child sacrifice). The story, so told, would function as a legitimation device for Lord’s Day worship.” [Charles H. Talbert, Reading Acts :<br />

A Literary and Theological Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, Rev. ed., Reading the New Testament Series (Macon, GA: Smyth<br />

& Helwys Publishing, 2005), 179.]<br />

This summation comes after the presenting of six different ancient texts negatively viewing religious meetings taking place at<br />

night time in the Greco-Roman world.<br />

203 “One can only hear the story with the ears of an ancient Mediterranean auditor if sufficient background is provided. The<br />

important thing to know is that nocturnal meetings were perceived negatively by Mediterranean society. On the one hand, nocturnal<br />

meetings were associated with political conspiracy: for example, Cicero, Catiline 1.1; 3.5–6; Juvenal, Satires 8.231–35; Pliny, Epistles<br />

10.96 — Christians had ceased their night meetings after Pliny’s edict in which, in accordance with Trajan’s orders, he had forbidden<br />

secret societies. On the other hand, night gatherings were thought to be connected with human sacrifice and sexual immorality. The following<br />

examples make this clear (so Daniel Hilty).” [Charles H. Talbert, Reading Acts : A Literary and Theological Commentary on the<br />

Acts of the Apostles, Rev. ed., Reading the New Testament Series (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, 2005), 177.]