Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Mov<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>forward</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zimbabwe</strong><br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g poverty and promot<strong>in</strong>g growth<br />

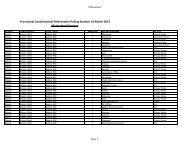

<strong>The</strong> comprehensive approach that the government pursued<br />

conta<strong>in</strong>ed five major social assistance programmes. First, the<br />

government sought to improve the wellbe<strong>in</strong>g of unskilled and<br />

semi-skilled labour through m<strong>in</strong>imum wage legislation. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

early 1980s, m<strong>in</strong>imum wages for domestic workers, agricultural<br />

workers, <strong>in</strong>dustrial workers and m<strong>in</strong>e workers were <strong>in</strong>creased by<br />

the government <strong>in</strong> an attempt to address aspects of the welfare gap<br />

produced by colonialism (see Table 8.2 below). <strong>The</strong> government<br />

augmented its m<strong>in</strong>imum wage policy by leverag<strong>in</strong>g control of<br />

the <strong>in</strong>herited price control system, to implement additional social<br />

assistance programmes. Through the price control <strong>in</strong>struments, the<br />

government kept the price of basic food commodities (maize meal,<br />

cook<strong>in</strong>g oil, bread, etc.) relatively low by subsidis<strong>in</strong>g producers.<br />

Second, <strong>in</strong> the 1980s <strong>Zimbabwe</strong> made significant welfare<br />

improvements by provid<strong>in</strong>g free health care to those earn<strong>in</strong>g less<br />

than Z$150 per month and their families, 1 erect<strong>in</strong>g and upgrad<strong>in</strong>g<br />

hospitals and rural health centres, 2 expand<strong>in</strong>g the immunisation<br />

programme to cover pregnant women and the six major childhood<br />

diseases, and <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g the Village Health Worker Programme<br />

(VHW) 3 and the Traditional Midwives Programme (TMP) to<br />

tra<strong>in</strong> local village-based health-care providers (M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health,<br />

1984; Agere, 1986). In addition to these health care programmes,<br />

the government also declared diarrhoea a national priority by<br />

launch<strong>in</strong>g the Diarrhoeal Disease Control Programme (DDCP).<br />

This programme also tra<strong>in</strong>ed mothers to properly prepare the oral<br />

hydration therapy solution (Cutts, 1984). F<strong>in</strong>ally, through the newly<br />

created National Nutrition Unit, the government adopted a host<br />

of nutritional programmes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Child Supplementary<br />

Feed<strong>in</strong>g Programme (CSFP). Through this programme, over<br />

250,000 under-nourished children <strong>in</strong> over 8,000 communal area<br />

feed<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>ts were provided with an energy-rich meal (Work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Group, 1982; M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health, 1984).<br />

As numerous scholars have noted, ‘education has always<br />

been <strong>in</strong> the forefront of politics <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zimbabwe</strong>…’ (Zvobgo,<br />

1987: 319). Dur<strong>in</strong>g the colonial period, restrict<strong>in</strong>g African access<br />

to education was one of the policies used by the settler state to<br />

protect, defend and reproduce white privilege. After <strong>in</strong>dependence<br />

the new government aggressively reformed the education system.<br />

Significantly, the government sought to achieve universal primary<br />

school education by abolish<strong>in</strong>g fees for primary education (Zvobgo,<br />

1987; Sanders and Davies 1988). Dur<strong>in</strong>g this period, there was an<br />

average annual <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> school enrolments of over 20 per cent:<br />

from 892,668 <strong>in</strong> 1979 to 2,727,162 by 1985 (CSO, 1986).<br />

Ga<strong>in</strong>s were not just limited to primary education. As bottlenecks<br />

<strong>in</strong> the education system <strong>in</strong>herited from the colonial period were<br />

removed, there were dramatic <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> enrolments at secondary<br />

schools and technical colleges. Compar<strong>in</strong>g enrolments <strong>in</strong> 1988<br />

with those <strong>in</strong> 1980, du Toit (1995) concludes that attendance at<br />

secondary schools was up by 771.5 per cent, and technical college<br />

enrolments were 623.7 per cent higher. In addition to expand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

student access to education, the government also committed itself<br />

to address<strong>in</strong>g the quality of education provided. This began with<br />

a 1982 decision to standardise student-teacher ratios nationally at<br />

1:40 for primary education, 1:30 for secondary education and 1:20<br />

for sixth-form students (Stoneman and Cliffe, 1989). To capture<br />

adults, the government also adopted an adult literacy programme.<br />

As noted by Sanders and Davies (1988), these changes had a double<br />

effect on the welfare status of the population: they contributed to<br />

the general welfare of the population through the <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic value of<br />

education; and free primary education <strong>in</strong>creased real <strong>in</strong>comes for<br />

households with school-age children.<br />

Similarly to the education system, the new government <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>Zimbabwe</strong> <strong>in</strong>herited an agricultural sector characterised by a highly<br />

skewed land ownership pattern (see Mandaza, 1987; Moyo, 1995,<br />

1987). Estimates put white ownership of prime agricultural land at<br />

well over 70 per cent, compared with less than 30 per cent owned<br />

by 90 per cent of the population. Although the government’s<br />

policies with respect to redress<strong>in</strong>g unequal land ownership fell well<br />

short of rural expectations, the new government took advantage<br />

of the Agricultural Market<strong>in</strong>g Authority and its market<strong>in</strong>g organs,<br />

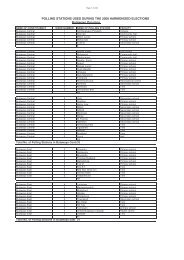

Table 8.2: Legislated monthly m<strong>in</strong>imum wage (nom<strong>in</strong>al Z$), 1980-86.<br />

Date<br />

Domestic workers Agricultural workers Industrial<br />

M<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g workers<br />

(a) (b) (a) (b) workers<br />

(a) (b)<br />

1 July 1980 30 (c) 30 (c) 70 43 70<br />

30 December 1980 30 (c) 30 (c) 85 58 85<br />

1 May 1981 -- -- -- -- -- (d) 85<br />

1 January 1982 50 62(e) 105 105<br />

1 September 1983 55 67 55 65 115 110<br />

1 July 1984 65 77 125 120<br />

1 July 1985 75 93 75 93 143 143<br />

1 July 1986 85 -- 85 -- 158 158<br />

Source: Sanders and Davies, 1988: 725.<br />

Notes: (a) For those workers who also received payments <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d.<br />

(b) For workers who did not receive payments <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d.<br />

(c) Benefits were to be added to cash wage.<br />

(d) M<strong>in</strong>eworkers not paid <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>d after this date.<br />

(e) Different grades of domestic workers recognised after this date.<br />

96