Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Mov<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>forward</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zimbabwe</strong><br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g poverty and promot<strong>in</strong>g growth<br />

3.8 Land reform and resettlement <strong>in</strong> post<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>Zimbabwe</strong> 1980-1992<br />

Upon atta<strong>in</strong>ment of <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong> 1980 the state was committed<br />

to a planned programme of land resettlement <strong>in</strong> accordance with<br />

the Lancaster house agreement. With match<strong>in</strong>g grants from the<br />

UK’s Overseas Development Adm<strong>in</strong>istration (now DfID), the<br />

state launched the <strong>in</strong>tensive resettlement programme <strong>in</strong> September<br />

1980, with the declared aim of resettl<strong>in</strong>g 18,000 families on 1.1<br />

million hectares of land over three years (Chitsike, 1988: 15).<br />

Land had been one of the core grievances that led to the war of<br />

liberation and as part of the Lancaster house settlement it had to<br />

be addressed somehow. What is clear however is that dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

transition to <strong>in</strong>dependence (1977-80) the <strong>Zimbabwe</strong>-Rhodesia<br />

state had produced a rural development plan that sought to create<br />

a smallholder irrigation-based resettlement programme. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

1979/80 f<strong>in</strong>ancial year 86,000ha of land had been acquired <strong>in</strong> the<br />

South Eastern Lowveld to resettle smallholders. This meant that at<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependence the only plans that existed revolved around produc<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a new breed of capitalist farmer on modern smallholder farms<br />

quite dist<strong>in</strong>ct from the communal lands. This was at variance with<br />

campaign manifestos published <strong>in</strong> December 1979 that seemed to<br />

show that the ma<strong>in</strong> guerrilla movement, if elected, would ‘promote<br />

on newly acquired land the establishment of collective villages<br />

and collective agriculture’. While the technocrats planned modern<br />

agricultural settlements, peasants emerg<strong>in</strong>g from the war wanted to<br />

spontaneously move onto white-owned commercial farmland to<br />

correct the land imbalance. In the end the programme announced<br />

by the state <strong>in</strong> September 1980 was driven by technocrats and<br />

sought to:<br />

• Alleviate population pressure <strong>in</strong> communal areas.<br />

• Extend and improve the base for productive agriculture<br />

<strong>in</strong> the peasant farm<strong>in</strong>g sector through <strong>in</strong>dividuals and cooperatives.<br />

• Improve standards of liv<strong>in</strong>g among the poorest sector of the<br />

population.<br />

• Ameliorate the plight of people affected by the war.<br />

• Provide opportunities for people who had no land and no<br />

employment, who may therefore be classified as destitute.<br />

• Achieve national stability and progress <strong>in</strong> a country that had<br />

recently emerged from the turmoil of war (GoZ, 1983).<br />

<strong>The</strong> programme targeted return<strong>in</strong>g refugees, those displaced by the<br />

war <strong>in</strong>ternally, the poor and unemployed, those displaced by large<br />

public projects and the landless. Purchases of 223,000 ha <strong>in</strong> the<br />

1980/81 f<strong>in</strong>ancial year and a further 1 million ha by the 1981/82<br />

season <strong>in</strong>creased the amount of land available considerably. By<br />

1982 the targets for resettlement had been scaled up to 35,000<br />

households, ris<strong>in</strong>g a year later to 162,000 on 9 million hectares <strong>in</strong><br />

plans announced <strong>in</strong> the Transitional National Development Plan of<br />

1983/84. <strong>The</strong> shift <strong>in</strong> the official target number of households to<br />

be resettled and even the basis for the targets is subject to different<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpretations. What is clear, however, is that <strong>in</strong> the early stages<br />

of the new <strong>Zimbabwe</strong> state, the policy pronouncements that had<br />

<strong>in</strong>itially been radical started to show a more neo-liberal tone. <strong>The</strong><br />

first official economic policy document was published <strong>in</strong> February<br />

1981 with the title ‘Growth with Equity’. With regards to the rural<br />

areas, fair land distribution was deemed a priority. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

the policy ‘land is a common heritage and no one should enjoy<br />

absolute ownership of it’ (p 4). <strong>The</strong> policy document, however, still<br />

described the resettlement programme as hav<strong>in</strong>g an ‘emphasis on<br />

voluntary co-operative arrangements among peasants’ (p 5).<br />

While the policy document talked about ‘build<strong>in</strong>g upon the<br />

traditional co-operative approach <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Zimbabwe</strong>an culture’,<br />

the technocrats at implementation level <strong>in</strong>sisted that resettlement<br />

processes and procedures were <strong>in</strong> place to ‘transform peasant<br />

agriculture, to remould society’ and discourage any attempts to<br />

revert back to traditional methods and systems of agriculture<br />

and adm<strong>in</strong>istration’ (Geza 1986): 37. What was clear at this po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

is that the college-tra<strong>in</strong>ed professionals had ideals that differed<br />

fundamentally from the political leadership. <strong>The</strong> factional divisions<br />

between the professionally-tra<strong>in</strong>ed technocrats concentrated <strong>in</strong><br />

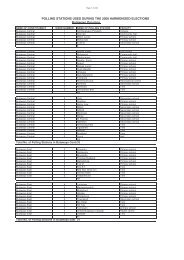

Model Name<br />

Model A –<br />

Normal<br />

Intensive<br />

Resettlement<br />

Model B –<br />

Cooperative<br />

Farm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Model C –<br />

Specialised<br />

Crop Farm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Model D –<br />

Livestock<br />

Ranch<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Table 3.4: Models for resettlement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zimbabwe</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1980s.<br />

Characteristics<br />

Individual settlement <strong>in</strong> nucleated villages with <strong>in</strong>dividual arable land allocation and communal<br />

graz<strong>in</strong>g. Each settler is allocated 5ha arable land and a graz<strong>in</strong>g right to depasture 4 to 10 livestock<br />

units depend<strong>in</strong>g on agro-ecological region. Households reside <strong>in</strong> nucleated village settlements. State<br />

provided the basic <strong>in</strong>frastructure before the settlers moved <strong>in</strong>. In the variant of model A, the Accelerated<br />

Intensive Resettlement Model, households moved <strong>in</strong> before <strong>in</strong>frastructure was <strong>in</strong> place. After 1992<br />

some model A2 were <strong>in</strong>troduced with self conta<strong>in</strong>ed residential and graz<strong>in</strong>g units.<br />

Cooperative ventures on farms suitable for specialised enterprises. State assistance <strong>in</strong> the form of<br />

establishment grants for equipment and technical assistance. Households resided <strong>in</strong> nucleated villages<br />

with basic <strong>in</strong>frastructure provided by the state.<br />

Resembled model A <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual plots except that it was based around a central estate that mentored<br />

the specialised farmers. Settlers contributed labour <strong>in</strong> return for free tillage, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and extension<br />

support. Used for sugar, tea and tobacco estates.<br />

Applicable to drier parts of the country. Initial version <strong>in</strong>volved resettl<strong>in</strong>g households on commercial<br />

ranches with a m<strong>in</strong>imum of arable land. A later variant the Three Tier System <strong>in</strong>volved nucleated<br />

villages where basic services were provided, then graz<strong>in</strong>g for five livestock units (subsistence use) and,<br />

the third layer had scope for 10 livestock units per household for commercial livestock production.<br />

Number resettled<br />

by November 1998<br />

51,006<br />

7,936<br />

636<br />

19,048<br />

Source: GoZ, 1998c: 6.<br />

44