Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Moving forward in Zimbabwe - Brooks World Poverty Institute - The ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Mov<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>forward</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zimbabwe</strong><br />

Reduc<strong>in</strong>g poverty and promot<strong>in</strong>g growth<br />

agricultural production growth has not kept pace with population<br />

growth. In addition, it is clear that the crisis has caused a severe<br />

decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> <strong>Zimbabwe</strong>an agriculture and the rural economy <strong>in</strong><br />

general. Key causes of this decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>clude:<br />

• Collapse <strong>in</strong> agricultural commodity market<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

pric<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> hyper-<strong>in</strong>flation environment (231 million per<br />

cent) gravely affected returns on agriculture – a factor that<br />

is not lost even on the illiterate farmers. This has meant that<br />

most people who used to produce for the formal market are<br />

reluctant to do so as the delays <strong>in</strong> process<strong>in</strong>g payments mean<br />

that by the time they are paid the money is worth noth<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Households that used to produce for the markets have<br />

stopped and produce mostly food crops for subsistence.<br />

• Asset attrition. <strong>The</strong> protracted decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the economy s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

2000 has also resulted <strong>in</strong> asset attrition as households sell<br />

off assets as a consumption smooth<strong>in</strong>g strategy. This often<br />

means sell<strong>in</strong>g off liquid assets that are also necessary for<br />

agricultural production. A decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> cattle numbers has been<br />

particularly obvious <strong>in</strong> some areas although <strong>in</strong> other areas the<br />

crisis has actually seen an <strong>in</strong>crease (Mavedzenge et al 2008).<br />

Lack of cattle underm<strong>in</strong>es availability of draught power and<br />

also compromises <strong>in</strong>come and consumption smooth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

strategies.<br />

• Labour shortage. <strong>The</strong>re is a basic assumption of labour<br />

abundance <strong>in</strong> rural <strong>Zimbabwe</strong> ow<strong>in</strong>g to displacement<br />

of former commercial farm workers. Available evidence<br />

suggests that apart from migration of the able bodied, an<br />

<strong>in</strong>ability to hire labour by the smallholder farmers means that<br />

labour shortage is a limit<strong>in</strong>g factor on production. Most able<br />

bodied young adults that provided family labour have either<br />

left rural <strong>Zimbabwe</strong> for other countries <strong>in</strong> the region or have<br />

opted for non-farm rural activities like artisanal m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. This<br />

has created labour constra<strong>in</strong>ts on production at the family<br />

farm. <strong>The</strong> lack of skills has become a limit<strong>in</strong>g factor. As<br />

experienced and tra<strong>in</strong>ed smallholder farmers have been dy<strong>in</strong>g<br />

off due to old age and HIV/AIDS the agricultural skills base<br />

has been underm<strong>in</strong>ed significantly.<br />

• Decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g soil fertility. Initial productivity <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong><br />

communal lands after the war could be accounted for by the<br />

virg<strong>in</strong> land effect. Once soil fertility decl<strong>in</strong>ed due to use over<br />

time the high external <strong>in</strong>puts model of production (hybrid<br />

seeds and fertiliser) that was <strong>in</strong>troduced has become too<br />

expensive to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>, especially given decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g profitability<br />

due to poor pric<strong>in</strong>g structure and lack of state support.<br />

• Dry<strong>in</strong>g out of private f<strong>in</strong>ance for agriculture. Once<br />

the state stopped support<strong>in</strong>g the smallholder farmers with<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts, most became <strong>in</strong>debted and failed to secure private<br />

f<strong>in</strong>ance needed for <strong>in</strong>puts. It is quite clear that dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

years follow<strong>in</strong>g a drought when some free <strong>in</strong>puts were made<br />

available there was always a productivity spike, especially <strong>in</strong><br />

food crops like maize. In the post-2000 period the demise of<br />

commercial farm<strong>in</strong>g that used to provide bridg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>come for<br />

<strong>in</strong>puts among resettled farmers has worsened the situation.<br />

Before the demise of large scale commercial farm<strong>in</strong>g some<br />

smallholder farmers could seek temporary employment on<br />

farms and used this to purchase <strong>in</strong>puts. Others relied on<br />

urban formal employment to generate the <strong>in</strong>puts. Once<br />

the large-scale farms were taken over dur<strong>in</strong>g the post-2000<br />

<strong>in</strong>vasions and the formal sector jobs began to decl<strong>in</strong>e due to<br />

the deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g economy this <strong>in</strong>come smooth<strong>in</strong>g strategy<br />

was no longer available.<br />

• Insecure tenure. Even if private f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g was still<br />

available, the terms under which land is accessed rema<strong>in</strong>s<br />

one of the key limit<strong>in</strong>g factors. It is clear that apart from<br />

the state and agricultural commodity brokers, f<strong>in</strong>ancial<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutions did not extend credit facilities to the resettled<br />

and communal farmers due to lack of tenure security. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

stopped support<strong>in</strong>g large scale commercial farmers once the<br />

land <strong>in</strong>vasions started. <strong>The</strong> productivity effects of this and<br />

all the above are apparent when we take a look at what has<br />

happened to maize production.<br />

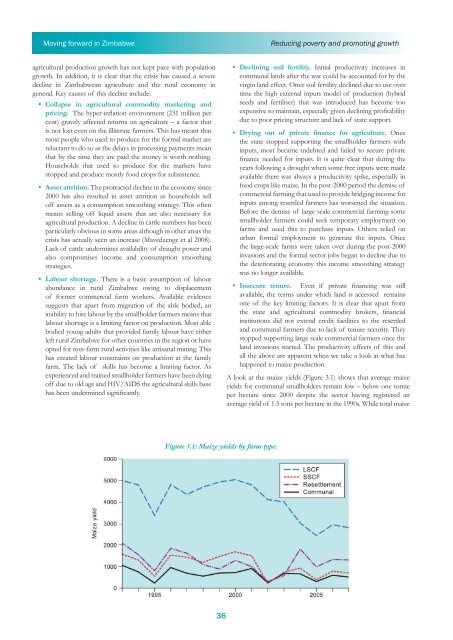

A look at the maize yields (Figure 3.1) shows that average maize<br />

yields for communal smallholders rema<strong>in</strong> low – below one tonne<br />

per hectare s<strong>in</strong>ce 2000 despite the sector hav<strong>in</strong>g registered an<br />

average yield of 1.5 tons per hectare <strong>in</strong> the 1990s. While total maize<br />

Figure 3.1: Maize yields by farm type.<br />

36