Shark Depredation and Unwanted Bycatch in Pelagic Longline

Shark Depredation and Unwanted Bycatch in Pelagic Longline

Shark Depredation and Unwanted Bycatch in Pelagic Longline

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Depredation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Unwanted</strong> <strong>Bycatch</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Pelagic</strong> Longl<strong>in</strong>e Fisheries<br />

the k<strong>in</strong>kai fleet, 0.175 (sd=0.0339), is higher by a factor of 8. Some of<br />

the potential reasons for this higher CPUE <strong>in</strong> the k<strong>in</strong>kai fleet have<br />

been explored <strong>in</strong> the previous section. Further <strong>in</strong>formation on the<br />

operational behavior of the k<strong>in</strong>kai fleet based on <strong>in</strong>terviews with<br />

fishermen is presented <strong>in</strong> Section A5.5.2.<br />

A5.3.4. Species composition of shark catches <strong>in</strong> longl<strong>in</strong>e<br />

fleets<br />

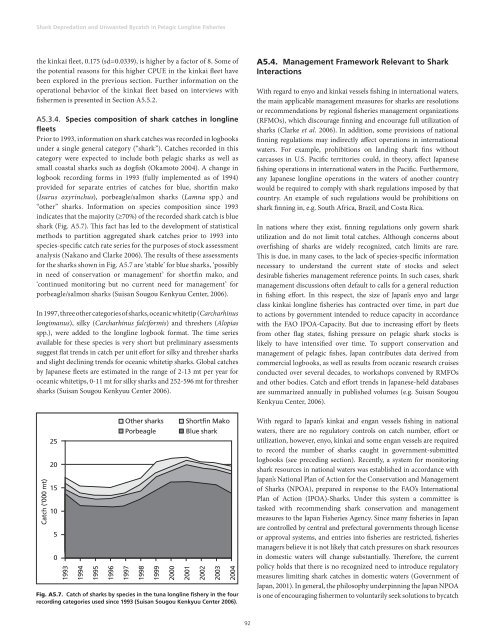

Prior to 1993, <strong>in</strong>formation on shark catches was recorded <strong>in</strong> logbooks<br />

under a s<strong>in</strong>gle general category (“shark”). Catches recorded <strong>in</strong> this<br />

category were expected to <strong>in</strong>clude both pelagic sharks as well as<br />

small coastal sharks such as dogfish (Okamoto 2004). A change <strong>in</strong><br />

logbook record<strong>in</strong>g forms <strong>in</strong> 1993 (fully implemented as of 1994)<br />

provided for separate entries of catches for blue, shortf<strong>in</strong> mako<br />

(Isurus oxyr<strong>in</strong>chus), porbeagle/salmon sharks (Lamna spp.) <strong>and</strong><br />

“other” sharks. Information on species composition s<strong>in</strong>ce 1993<br />

<strong>in</strong>dicates that the majority (≥70%) of the recorded shark catch is blue<br />

shark (Fig. A5.7). This fact has led to the development of statistical<br />

methods to partition aggregated shark catches prior to 1993 <strong>in</strong>to<br />

species-specific catch rate series for the purposes of stock assessment<br />

analysis (Nakano <strong>and</strong> Clarke 2006). The results of these assessments<br />

for the sharks shown <strong>in</strong> Fig. A5.7 are ‘stable’ for blue sharks, ‘possibly<br />

<strong>in</strong> need of conservation or management’ for shortf<strong>in</strong> mako, <strong>and</strong><br />

‘cont<strong>in</strong>ued monitor<strong>in</strong>g but no current need for management’ for<br />

porbeagle/salmon sharks (Suisan Sougou Kenkyuu Center, 2006).<br />

In 1997, three other categories of sharks, oceanic whitetip (Carcharh<strong>in</strong>us<br />

longimanus), silky (Carcharh<strong>in</strong>us falciformis) <strong>and</strong> threshers (Alopias<br />

spp.), were added to the longl<strong>in</strong>e logbook format. The time series<br />

available for these species is very short but prelim<strong>in</strong>ary assessments<br />

suggest flat trends <strong>in</strong> catch per unit effort for silky <strong>and</strong> thresher sharks<br />

<strong>and</strong> slight decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g trends for oceanic whitetip sharks. Global catches<br />

by Japanese fleets are estimated <strong>in</strong> the range of 2-13 mt per year for<br />

oceanic whitetips, 0-11 mt for silky sharks <strong>and</strong> 252-596 mt for thresher<br />

sharks (Suisan Sougou Kenkyuu Center 2006).<br />

A5.4. Management Framework Relevant to <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Interactions<br />

With regard to enyo <strong>and</strong> k<strong>in</strong>kai vessels fish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational waters,<br />

the ma<strong>in</strong> applicable management measures for sharks are resolutions<br />

or recommendations by regional fisheries management organizations<br />

(RFMOs), which discourage f<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> encourage full utilization of<br />

sharks (Clarke et al. 2006). In addition, some provisions of national<br />

f<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g regulations may <strong>in</strong>directly affect operations <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational<br />

waters. For example, prohibitions on l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g shark f<strong>in</strong>s without<br />

carcasses <strong>in</strong> U.S. Pacific territories could, <strong>in</strong> theory, affect Japanese<br />

fish<strong>in</strong>g operations <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational waters <strong>in</strong> the Pacific. Furthermore,<br />

any Japanese longl<strong>in</strong>e operations <strong>in</strong> the waters of another country<br />

would be required to comply with shark regulations imposed by that<br />

country. An example of such regulations would be prohibitions on<br />

shark f<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>, e.g. South Africa, Brazil, <strong>and</strong> Costa Rica.<br />

In nations where they exist, f<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g regulations only govern shark<br />

utilization <strong>and</strong> do not limit total catches. Although concerns about<br />

overfish<strong>in</strong>g of sharks are widely recognized, catch limits are rare.<br />

This is due, <strong>in</strong> many cases, to the lack of species-specific <strong>in</strong>formation<br />

necessary to underst<strong>and</strong> the current state of stocks <strong>and</strong> select<br />

desirable fisheries management reference po<strong>in</strong>ts. In such cases, shark<br />

management discussions often default to calls for a general reduction<br />

<strong>in</strong> fish<strong>in</strong>g effort. In this respect, the size of Japan’s enyo <strong>and</strong> large<br />

class k<strong>in</strong>kai longl<strong>in</strong>e fisheries has contracted over time, <strong>in</strong> part due<br />

to actions by government <strong>in</strong>tended to reduce capacity <strong>in</strong> accordance<br />

with the FAO IPOA-Capacity. But due to <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g effort by fleets<br />

from other flag states, fish<strong>in</strong>g pressure on pelagic shark stocks is<br />

likely to have <strong>in</strong>tensified over time. To support conservation <strong>and</strong><br />

management of pelagic fishes, Japan contributes data derived from<br />

commercial logbooks, as well as results from oceanic research cruises<br />

conducted over several decades, to workshops convened by RMFOs<br />

<strong>and</strong> other bodies. Catch <strong>and</strong> effort trends <strong>in</strong> Japanese-held databases<br />

are summarized annually <strong>in</strong> published volumes (e.g. Suisan Sougou<br />

Kenkyuu Center, 2006).<br />

Fig. A5.7. Catch of sharks by species <strong>in</strong> the tuna longl<strong>in</strong>e fishery <strong>in</strong> the four<br />

record<strong>in</strong>g categories used s<strong>in</strong>ce 1993 (Suisan Sougou Kenkyuu Center 2006).<br />

With regard to Japan’s k<strong>in</strong>kai <strong>and</strong> engan vessels fish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> national<br />

waters, there are no regulatory controls on catch number, effort or<br />

utilization, however, enyo, k<strong>in</strong>kai <strong>and</strong> some engan vessels are required<br />

to record the number of sharks caught <strong>in</strong> government-submitted<br />

logbooks (see preced<strong>in</strong>g section). Recently, a system for monitor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

shark resources <strong>in</strong> national waters was established <strong>in</strong> accordance with<br />

Japan’s National Plan of Action for the Conservation <strong>and</strong> Management<br />

of <strong>Shark</strong>s (NPOA), prepared <strong>in</strong> response to the FAO’s International<br />

Plan of Action (IPOA)-<strong>Shark</strong>s. Under this system a committee is<br />

tasked with recommend<strong>in</strong>g shark conservation <strong>and</strong> management<br />

measures to the Japan Fisheries Agency. S<strong>in</strong>ce many fisheries <strong>in</strong> Japan<br />

are controlled by central <strong>and</strong> prefectural governments through license<br />

or approval systems, <strong>and</strong> entries <strong>in</strong>to fisheries are restricted, fisheries<br />

managers believe it is not likely that catch pressures on shark resources<br />

<strong>in</strong> domestic waters will change substantially. Therefore, the current<br />

policy holds that there is no recognized need to <strong>in</strong>troduce regulatory<br />

measures limit<strong>in</strong>g shark catches <strong>in</strong> domestic waters (Government of<br />

Japan, 2001). In general, the philosophy underp<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g the Japan NPOA<br />

is one of encourag<strong>in</strong>g fishermen to voluntarily seek solutions to bycatch<br />

92