An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity - always yours

An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity - always yours

An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity - always yours

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

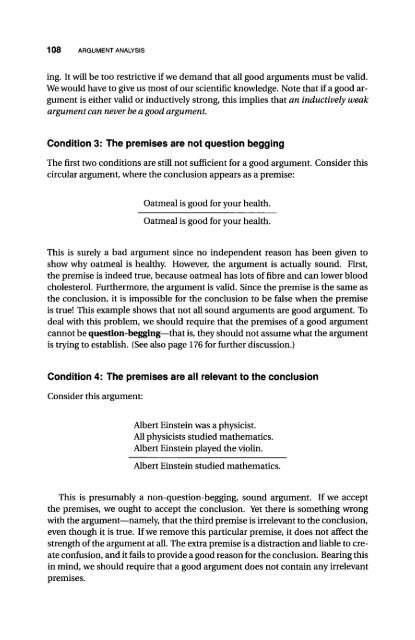

108 ARGUMENT ANALYSIS<br />

ing. It will be <strong>to</strong>o restrictive if we dem<strong>and</strong> that all good arguments must be valid.<br />

We would have <strong>to</strong> give us most of our scientific knowledge. Note that if a good argument<br />

is either valid or inductively strong, this implies that an inductively weak<br />

argument can never be a good argument.<br />

Condition 3: The premises are not question begging<br />

The first two conditions are still not sufficient for a good argument. Consider this<br />

circular argument, where the conclusion appears as a premise:<br />

Oatmeal is good for your health.<br />

Oatmeal is good for your health.<br />

This is surely a bad argument since no independent reason has been given <strong>to</strong><br />

show why oatmeal is healthy. However, the argument is actually sound. First,<br />

the premise is indeed true, because oatmeal has lots of fibre <strong>and</strong> can lower blood<br />

cholesterol. Furthermore, the argument is valid. Since the premise is the same as<br />

the conclusion, it is impossible for the conclusion <strong>to</strong> be false when the premise<br />

is true! This example shows that not all sound arguments are good argument. To<br />

deal with this problem, we should require that the premises of a good argument<br />

cannot be question-begging—that is, they should not assume what the argument<br />

is trying <strong>to</strong> establish. (See also page 176 for further discussion.)<br />

Condition 4: The premises are all relevant <strong>to</strong> the conclusion<br />

Consider this argument:<br />

Albert Einstein was a physicist.<br />

All physicists studied mathematics.<br />

Albert Einstein played the violin.<br />

Albert Einstein studied mathematics.<br />

This is presumably a non-question-begging, sound argument. If we accept<br />

the premises, we ought <strong>to</strong> accept the conclusion. Yet there is something wrong<br />

with the argument—namely, that the third premise is irrelevant <strong>to</strong> the conclusion,<br />

even though it is true. If we remove this particular premise, it does not affect the<br />

strength of the argument at all. The extra premise is a distraction <strong>and</strong> liable <strong>to</strong> create<br />

confusion, <strong>and</strong> it fails <strong>to</strong> provide a good reason for the conclusion. Bearing this<br />

in mind, we should require that a good argument does not contain any irrelevant<br />

premises.