The Winton M. Blount Postal History Symposia - Smithsonian ...

The Winton M. Blount Postal History Symposia - Smithsonian ...

The Winton M. Blount Postal History Symposia - Smithsonian ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

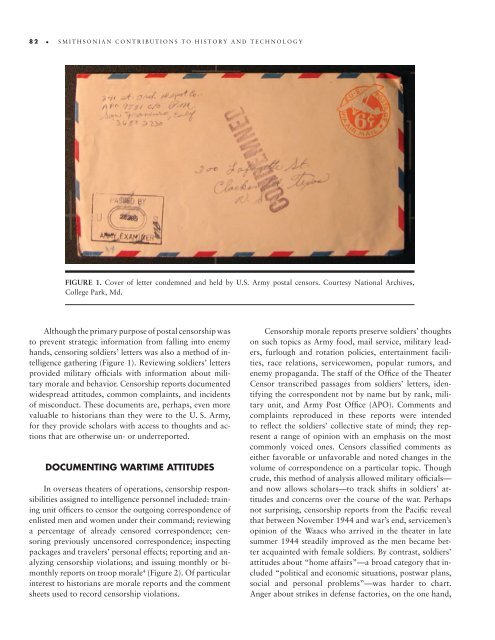

8 2 • s m i t h s o n i a n c o n t r i b u t i o n s t o h i s t o ry a n d t e c h n o l o g yFigure 1. Cover of letter condemned and held by U.S. Army postal censors. Courtesy National Archives,College Park, Md.Although the primary purpose of postal censorship wasto prevent strategic information from falling into enemyhands, censoring soldiers’ letters was also a method of intelligencegathering (Figure 1). Reviewing soldiers’ lettersprovided military officials with information about militarymorale and behavior. Censorship reports documentedwidespread attitudes, common complaints, and incidentsof misconduct. <strong>The</strong>se documents are, perhaps, even morevaluable to historians than they were to the U. S. Army,for they provide scholars with access to thoughts and actionsthat are otherwise un- or underreported.Documenting Wartime AttitudesIn overseas theaters of operations, censorship responsibilitiesassigned to intelligence personnel included: trainingunit officers to censor the outgoing correspondence ofenlisted men and women under their command; reviewinga percentage of already censored correspondence; censoringpreviously uncensored correspondence; inspectingpackages and travelers’ personal effects; reporting and analyzingcensorship violations; and issuing monthly or bimonthlyreports on troop morale 4 (Figure 2). Of particularinterest to historians are morale reports and the commentsheets used to record censorship violations.Censorship morale reports preserve soldiers’ thoughtson such topics as Army food, mail service, military leaders,furlough and rotation policies, entertainment facilities,race relations, servicewomen, popular rumors, andenemy propaganda. <strong>The</strong> staff of the Office of the <strong>The</strong>aterCensor transcribed passages from soldiers’ letters, identifyingthe correspondent not by name but by rank, militaryunit, and Army Post Office (APO). Comments andcomplaints reproduced in these reports were intendedto reflect the soldiers’ collective state of mind; they representa range of opinion with an emphasis on the mostcommonly voiced ones. Censors classified comments aseither favorable or unfavorable and noted changes in thevolume of correspondence on a particular topic. Thoughcrude, this method of analysis allowed military officials—and now allows scholars—to track shifts in soldiers’ attitudesand concerns over the course of the war. Perhapsnot surprising, censorship reports from the Pacific revealthat between November 1944 and war’s end, servicemen’sopinion of the Waacs who arrived in the theater in latesummer 1944 steadily improved as the men became betteracquainted with female soldiers. By contrast, soldiers’attitudes about “home affairs”—a broad category that included“political and economic situations, postwar plans,social and personal problems”—was harder to chart.Anger about strikes in defense factories, on the one hand,