October 2006 Volume 9 Number 4

October 2006 Volume 9 Number 4

October 2006 Volume 9 Number 4

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

courses where it is has little potential benefit, or use of the technology at an incorrect or superficial level. Such<br />

initiatives are often characterized by replication, where the technology maintains an existing teacher-centric<br />

pedagogy without change, or simple redundancy, where the online development is both supplementary and<br />

superfluous to the existing pedagogy.<br />

‘Cultural’ inconsistencies arise when the institution’s policies and practice do not support pedagogical<br />

developments, or where either teachers or students are unaccepting of it, despite the availability of both<br />

resources and knowledge. Many technically-robust and comprehensive ‘platform’ developments at universities<br />

have failed to solicit the appropriate utilization by those teachers and courses that could potentially benefit from<br />

these and do not establish ‘critical mass’ that might embed the pedagogy at an institutional level.<br />

‘Resource’ inconsistencies arise either when an institution lacks the physical resources to realize the<br />

developments possible given the available knowledge and culture, or where it is seduced by the “rapture of<br />

technology” (Ehrmann, 2002), and sponsors initiatives that are too resource-demanding in their development,<br />

evolution, and maintenance to have any hope of long-term continuation. These latter ‘bells and whistles’<br />

initiatives are characterized by focus on advanced technology rather than education, and consequently often<br />

evolve extended and convoluted structure, and large technology costs. Such initiatives require a high level of<br />

continuing technical support beyond that immediately available by or to the teacher. While being eminent<br />

‘institutional show-pieces’, they demonstrate excessive cost for limited benefit, and are typically either transient,<br />

with a lifespan tied to funding availability, or static after their initial development.<br />

At HKU, there appear no inconsistencies within the student body that present a major impediment to online<br />

development. It is apparent that the required technical literacy and technological acceptance of internet-based<br />

teaching is established. Students are quick to identify the advantages of this methodology and determine which<br />

courses would lend themselves to it. The reluctance of some students to assume the challenge of student-centered<br />

pedagogies may be expected to reduce with growing familiarity. Resource availability is exceptionally high.<br />

The major hindrances to the development of online learning at HKU appear to lie largely in institutional<br />

inconsistencies, particularly those of culture, pedagogic knowledge, and non-hardware resources.<br />

Institutional culture<br />

The ‘culture’ within an institution is significantly framed by its strategic and internal policies, and consequent<br />

reward structures. HKU is currently pursuing market ‘niching’ through elitism and ‘excellence’ largely<br />

dominated by quantified research publication, as have many ‘first-founded’ state universities worldwide. This<br />

developing and unambiguous research focus has strengthened a perception that teaching and education aspects of<br />

scholarship are not the primary focus in university career paths, dominantly rewarding discipline-based<br />

publication.<br />

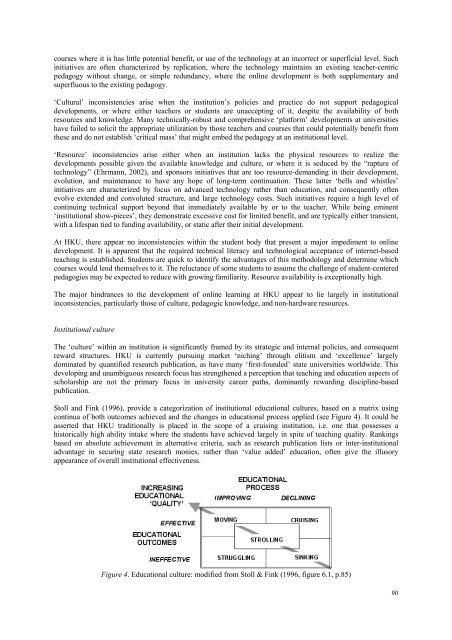

Stoll and Fink (1996), provide a categorization of institutional educational cultures, based on a matrix using<br />

continua of both outcomes achieved and the changes in educational process applied (see Figure 4). It could be<br />

asserted that HKU traditionally is placed in the scope of a cruising institution, i.e. one that possesses a<br />

historically high ability intake where the students have achieved largely in spite of teaching quality. Rankings<br />

based on absolute achievement in alternative criteria, such as research publication lists or inter-institutional<br />

advantage in securing state research monies, rather than ‘value added’ education, often give the illusory<br />

appearance of overall institutional effectiveness.<br />

Figure 4. Educational culture: modified from Stoll & Fink (1996, figure 6.1, p.85)<br />

90