- Page 2:

This page intentionally left blank

- Page 8:

Brief ContentsPrefacexiPART IGenera

- Page 12:

Contents vINDIRECT (UNOBTRUSIVE) OB

- Page 16: Contents viiQUASI-EXPERIMENTS 321Th

- Page 20: About the AuthorsJOHN J. SHAUGHNESS

- Page 24: PrefaceWith this 9th edition we mar

- Page 28: Preface xiiimuch information that n

- Page 32: Preface xvFor StudentsMultiple choi

- Page 36: PART ONEGeneral Issues

- Page 40: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 3THE SCIENC

- Page 44: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 5FIGURE 1.1

- Page 48: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 7Key Concep

- Page 52: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 9FIGURE 1.2

- Page 56: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 11character

- Page 60: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 13an exampl

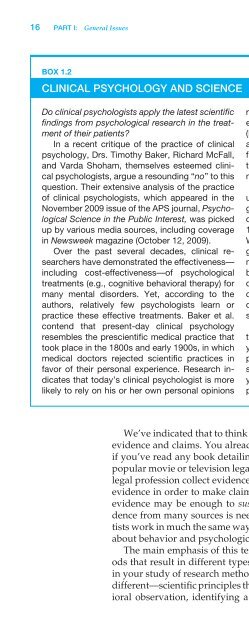

- Page 64: CHAPTER 1: Introduction 15THINKING

- Page 70: 18 PART I: General Issuescan give y

- Page 74: 20 PART I: General Issuesbefore beg

- Page 78: 22 PART I: General IssuesTABLE 1.1S

- Page 82: 24 PART I: General Issuesmedia repo

- Page 86: 26 PART I: General Issuesparticipan

- Page 90: 28 PART I: General IssuesSCIENTIFIC

- Page 94: 30 PART I: General IssuesThe scient

- Page 98: 32 PART I: General IssuesBOX 2.1CAN

- Page 102: 34 PART I: General IssuesFIGURE 2.2

- Page 106: 36 PART I: General Issuesand measur

- Page 110: 38 PART I: General IssuesKey Concep

- Page 114: 40 PART I: General Issuestestable h

- Page 118:

42 PART I: General IssuesFIGURE 2.4

- Page 122:

44 PART I: General IssuesQualitativ

- Page 126:

46 PART I: General IssuesKey Concep

- Page 130:

48 PART I: General IssuesKey Concep

- Page 134:

50 PART I: General IssuesKey Concep

- Page 138:

52 PART I: General Issuesindependen

- Page 142:

54 PART I: General Issuescauses be

- Page 146:

56 PART I: General IssuesInternet t

- Page 150:

58 PART I: General IssuesINTRODUCTI

- Page 154:

60 PART I: General IssuesFIGURE 3.1

- Page 158:

62 PART I: General IssuesViolation

- Page 162:

64 PART I: General IssuesKey Concep

- Page 166:

66 PART I: General IssuesSTRETCHING

- Page 170:

68 PART I: General IssuesResearcher

- Page 174:

70 PART I: General IssuesBOX 3.1TIP

- Page 178:

72 PART I: General IssuesSTRETCHING

- Page 182:

74 PART I: General IssuesBOX 3.2TO

- Page 186:

76 PART I: General IssuesKelman (19

- Page 190:

78 PART I: General Issuesa particul

- Page 194:

80 PART I: General IssuesFIGURE 3.8

- Page 198:

82 PART I: General Issues• Proper

- Page 202:

84 PART I: General IssuesTABLE 3.1E

- Page 206:

86 PART I: General Issuesresearch.

- Page 210:

88 PART I: General Issuesattitudes

- Page 214:

90 PART I: General Issuesthe benefi

- Page 218:

CHAPTER FOURObservationCHAPTER OUTL

- Page 222:

94 PART II: Descriptive MethodsSAMP

- Page 226:

96 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 230:

98 PART II: Descriptive MethodsBOX

- Page 234:

100 PART II: Descriptive MethodsHar

- Page 238:

102 PART II: Descriptive MethodsBOX

- Page 242:

104 PART II: Descriptive MethodsFIG

- Page 246:

106 PART II: Descriptive Methodsbet

- Page 250:

108 PART II: Descriptive Methodscan

- Page 254:

110 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 258:

112 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 262:

114 PART II: Descriptive Methodsthr

- Page 266:

116 PART II: Descriptive MethodsBOX

- Page 270:

118 PART II: Descriptive MethodsTAB

- Page 274:

120 PART II: Descriptive Methods•

- Page 278:

122 PART II: Descriptive Methods(Wh

- Page 282:

124 PART II: Descriptive MethodsTAB

- Page 286:

126 PART II: Descriptive Methodstim

- Page 290:

128 PART II: Descriptive Methods(Fe

- Page 294:

130 PART II: Descriptive Methodstop

- Page 298:

132 PART II: Descriptive MethodsOth

- Page 302:

134 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKEY

- Page 306:

136 PART II: Descriptive Methodswer

- Page 310:

138 PART II: Descriptive MethodsOVE

- Page 314:

140 PART II: Descriptive Methodsque

- Page 318:

142 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 322:

144 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 326:

146 PART II: Descriptive MethodsBOX

- Page 330:

148 PART II: Descriptive MethodsSTR

- Page 334:

150 PART II: Descriptive MethodsPer

- Page 338:

152 PART II: Descriptive Methodsmay

- Page 342:

154 PART II: Descriptive MethodsIRB

- Page 346:

156 PART II: Descriptive MethodsFIG

- Page 350:

158 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 354:

160 PART II: Descriptive Methodssam

- Page 358:

162 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 362:

164 PART II: Descriptive Methodsfee

- Page 366:

166 PART II: Descriptive MethodsTAB

- Page 370:

168 PART II: Descriptive Methods3 W

- Page 374:

170 PART II: Descriptive Methodsto

- Page 378:

172 PART II: Descriptive Methodssel

- Page 382:

174 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 386:

176 PART II: Descriptive MethodsKey

- Page 390:

178 PART II: Descriptive MethodsSam

- Page 394:

180 PART II: Descriptive MethodsCHA

- Page 398:

182 PART II: Descriptive Methods2 A

- Page 402:

CHAPTER SIXIndependent Groups Desig

- Page 406:

186 PART III: Experimental MethodsP

- Page 410:

188 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 414:

190 PART III: Experimental MethodsF

- Page 418:

192 PART III: Experimental Methodst

- Page 422:

194 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 426:

196 PART III: Experimental Methodsd

- Page 430:

198 PART III: Experimental MethodsS

- Page 434:

200 PART III: Experimental MethodsT

- Page 438:

202 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 442:

204 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 446:

206 PART III: Experimental MethodsB

- Page 450:

208 PART III: Experimental Methodsy

- Page 454:

210 PART III: Experimental Methodsm

- Page 458:

212 PART III: Experimental Methodsa

- Page 462:

214 PART III: Experimental MethodsT

- Page 466:

216 PART III: Experimental MethodsF

- Page 470:

218 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 474:

220 PART III: Experimental Methodsd

- Page 478:

222 PART III: Experimental MethodsC

- Page 482:

224 PART III: Experimental Methods3

- Page 486:

226 PART III: Experimental MethodsO

- Page 490:

228 PART III: Experimental MethodsB

- Page 494:

230 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 498:

232 PART III: Experimental Methodsr

- Page 502:

234 PART III: Experimental MethodsT

- Page 506:

236 PART III: Experimental Methodst

- Page 510:

238 PART III: Experimental MethodsT

- Page 514:

240 PART III: Experimental MethodsD

- Page 518:

242 PART III: Experimental Methodsc

- Page 522:

244 PART III: Experimental MethodsC

- Page 526:

246 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 530:

248 PART III: Experimental MethodsA

- Page 534:

250 PART III: Experimental MethodsO

- Page 538:

252 PART III: Experimental Methodsi

- Page 542:

254 PART III: Experimental MethodsT

- Page 546:

256 PART III: Experimental MethodsK

- Page 550:

258 PART III: Experimental MethodsS

- Page 554:

260 PART III: Experimental Methodsm

- Page 558:

262 PART III: Experimental Methods

- Page 562:

264 PART III: Experimental Methods

- Page 566:

266 PART III: Experimental Methodsc

- Page 570:

268 PART III: Experimental Methods(

- Page 574:

270 PART III: Experimental MethodsI

- Page 578:

272 PART III: Experimental MethodsF

- Page 582:

274 PART III: Experimental MethodsH

- Page 586:

276 PART III: Experimental Methodsi

- Page 590:

278 PART III: Experimental Methods(

- Page 594:

CHAPTER NINESingle-Case Designs and

- Page 598:

282 PART IV: Applied Researchintere

- Page 602:

284 PART IV: Applied Researcharticl

- Page 606:

286 PART IV: Applied Researchor uni

- Page 610:

288 PART IV: Applied ResearchSTRETC

- Page 614:

290 PART IV: Applied ResearchSusan

- Page 618:

292 PART IV: Applied ResearchFIGURE

- Page 622:

294 PART IV: Applied ResearchKey Co

- Page 626:

296 PART IV: Applied Research• Et

- Page 630:

298 PART IV: Applied ResearchBOX 9.

- Page 634:

300 PART IV: Applied ResearchKey Co

- Page 638:

302 PART IV: Applied Researchwoven

- Page 642:

304 PART IV: Applied ResearchFIGURE

- Page 646:

306 PART IV: Applied Researchof beh

- Page 650:

308 PART IV: Applied ResearchB Expl

- Page 654:

310 PART IV: Applied ResearchOVERVI

- Page 658:

312 PART IV: Applied ResearchBOX 10

- Page 662:

314 PART IV: Applied Researchsuch c

- Page 666:

316 PART IV: Applied ResearchKey Co

- Page 670:

318 PART IV: Applied Researchthat a

- Page 674:

320 PART IV: Applied ResearchOne sp

- Page 678:

322 PART IV: Applied ResearchQuasi-

- Page 682:

324 PART IV: Applied ResearchThe da

- Page 686:

326 PART IV: Applied ResearchFIGURE

- Page 690:

328 PART IV: Applied Researchassign

- Page 694:

330 PART IV: Applied ResearchDiffer

- Page 698:

332 PART IV: Applied ResearchKey Co

- Page 702:

334 PART IV: Applied ResearchFIGURE

- Page 706:

336 PART IV: Applied ResearchAs bef

- Page 710:

338 PART IV: Applied Research(effic

- Page 714:

340 PART IV: Applied Researchsocial

- Page 718:

342 PART IV: Applied ResearchKEY CO

- Page 722:

344 PART IV: Applied ResearchAnswer

- Page 726:

CHAPTER ELEVENData Analysis and Int

- Page 730:

348 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 734:

350 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 738:

352 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 742:

354 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 746:

356 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 750:

358 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 754:

360 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 758:

362 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 762:

364 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 766:

366 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 770:

368 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 774:

370 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 778:

372 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 782:

374 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 786:

376 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 790:

378 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 794:

380 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 798:

or382 PART V: Analyzing and Reporti

- Page 802:

384 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 806:

386 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 810:

388 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 814:

390 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 818:

392 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 822:

394 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 826:

396 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 830:

398 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 834:

400 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 838:

402 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 842:

404 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 846:

406 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 850:

408 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 854:

410 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 858:

412 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 862:

414 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 866:

416 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 870:

418 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 874:

420 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 878:

422 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 882:

424 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 886:

426 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 890:

428 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 894:

430 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 898:

432 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 902:

434 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 906:

436 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 910:

438 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 914:

440 PART V: Analyzing and Reporting

- Page 918:

AppendixStatistical TablesAPPENDIX

- Page 922:

444 APPENDIX: Statistical TablesTAB

- Page 926:

446 APPENDIX: Statistical TablesTAB

- Page 930:

448 Glossarycomparison of two means

- Page 934:

450 Glossaryinformed consent Explic

- Page 938:

452 Glossaryparticipant observation

- Page 942:

454 Glossarysimple main effect Effe

- Page 946:

ReferencesAbelson, R. P. (1995). St

- Page 950:

458 ReferencesBoring, E. G. (1954).

- Page 954:

460 ReferencesEvans, R., & Donnerst

- Page 958:

462 ReferencesHolden, C. (1987). An

- Page 962:

464 ReferencesKruglanski, A. W., Cr

- Page 966:

466 ReferencesMiles, M. B., & Huber

- Page 970:

468 ReferencesRichardson, J. & Parn

- Page 974:

470 ReferencesSokal, M. M. (1992).

- Page 978:

CreditsChapter 1Figure 1.1a: © Ima

- Page 982:

474 Credits9.1b: © Bettmann/Corbis

- Page 986:

476 Name IndexDolan, C. A., 119Donn

- Page 990:

478 Name IndexRosenthal, R., 45-46,

- Page 994:

480 Subject IndexBlock randomizatio

- Page 998:

482 Subject IndexExperiment (Contin

- Page 1002:

484 Subject IndexNonprobability sam

- Page 1006:

486 Subject IndexResearch report wr

- Page 1010:

488 Subject IndexVariables (types)d