Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Syncytia usually are elongate, with ends merging with normal<br />

tissue, and each syncytium is generally associated with one<br />

larva. When multiple infections occur within a small area <strong>of</strong> root<br />

tissue, syncytia may coalesce. Nuclear hypertrophv is followed<br />

by decrease in size and nu<strong>mb</strong>er <strong>of</strong> plastids, breakdown <strong>of</strong><br />

chond riosomes (mi tochondi ra). polyploid y <strong>of</strong> nuclei, and<br />

nuclear disintegration,<br />

Ingrowths or protuberances d'eslop next to xylem vessels;<br />

"boundary formations" and microtubules are associated with<br />

the ends <strong>of</strong> these protuberances. Ihey serve to increase the<br />

surface area <strong>of</strong> the syncytial cell wall relative to its volume and to<br />

allow for increased flow <strong>of</strong> solutes across the plasmalemma. The<br />

cell wall becomes tip to 10 times its normal thickness.<br />

Epidemiology<br />

Although populations <strong>of</strong> cyst nematodes do not increase as<br />

rapidly as do fungal and bacterial pathogens <strong>of</strong> potatoes, once<br />

well established in a potato-growing area, they arc. with present<br />

technology, inipossihlc to eradicate. The environmental<br />

conditons providing successful cotomLr'iAl potato production<br />

also provide optimum conditions for their multiplication and<br />

survival. <strong>Potato</strong> cyst neniatodes flourish where soil<br />

temperatures are cool. Although they have been found in<br />

tropical and warmer temperate climates, they. do not generally<br />

become established and are <strong>of</strong> lesser economic importance than<br />

in cool climates, larvae become active at IO C. and maximum<br />

invasion <strong>of</strong> roots occurs at 160 C. Soil temperatures <strong>of</strong> 260 C for<br />

prolonged periods <strong>of</strong> time reduce development and limit<br />

reproduction.<br />

Cyst nernatodes develop well in soils suited for surviva! and<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> wormlike stages, such as medium to heavy clay<br />

soils and well-drained and aerated sands, silts, and peat soils<br />

with a moisture content <strong>of</strong> 50-75(i <strong>of</strong> water capacity. Soil pH<br />

valles that are tolerable to the potato plant can apparently be<br />

tolerated by the nematodes. Nutritional status <strong>of</strong> the soil<br />

.pp.<br />

_l •<br />

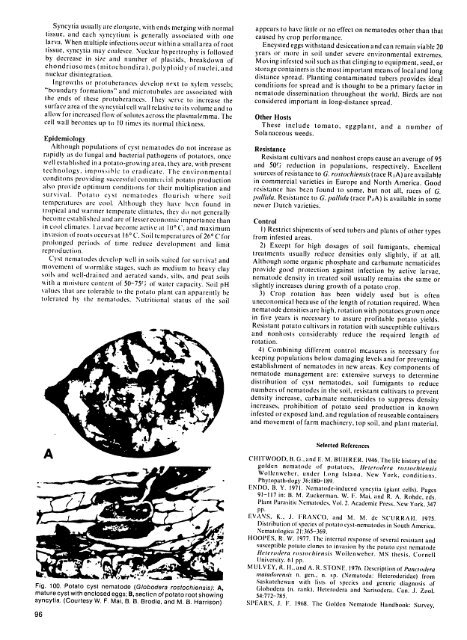

Fig. 100. <strong>Potato</strong> cyst nematode (Globodera rostochiensis): A,<br />

mature cyst with enclosed eggs; B,sectien <strong>of</strong> potato root showing<br />

syncytia. (Courtesy W.F. Mai, B. B. Brodie, and M. B. Harrison)<br />

96<br />

;10<br />

appears to have little or no effect on nematodes other than that<br />

caused by crop performance.<br />

Encysted eggs withstand desiccation and can remain viable 20<br />

years or more in soil under severe environmental extremes.<br />

Moving infested soil such as that clinging to equipment, seed, or<br />

storage containers is the most important means <strong>of</strong> local and long<br />

distance spread. Planting contaminated tubers provides ideal<br />

conditions for spread and is thought to be a primary factor in<br />

nematode dissemination throughout the world. Birds are not<br />

considered important in long-distance spread.<br />

Other Hosts<br />

These include tomato, eggplant, and a nu<strong>mb</strong>er <strong>of</strong><br />

Solanaceous weeds.<br />

Resistance<br />

Resistant cultivars and nonhost crops cause an average <strong>of</strong> 95<br />

and 50i reduction in populations, respectively. Excellent<br />

sources <strong>of</strong> resistance to G. rostochiensis(race R A) are available<br />

in commercial varieties in Europe and North America. Good<br />

resistance has been found to some, but not all, races <strong>of</strong> G.<br />

pallida. Resistance to G.pallida (race P 4A) is available in some<br />

ne%%er Dutch varieties.<br />

Control<br />

I) Restrict shipments <strong>of</strong> seed tubers and plants <strong>of</strong> other types<br />

from infested areas.<br />

2) Except for high dosages <strong>of</strong> soil fumigants, chemical<br />

treatments usually reduce densities only slightly, if at all.<br />

Although some organic phosphate and carbamate nematicides<br />

provide good protection against infection by active larvae,<br />

nematode density in treated soil usually remains the same or<br />

slightly increases during growth <strong>of</strong> a potato crop.<br />

3) Crop rotation has been widely used but is <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

uneconomical because <strong>of</strong>the length <strong>of</strong> rotation required. When<br />

nematode densities are high, rotation with potatoes grown once<br />

in five years is necessary to assure pr<strong>of</strong>itable potato yields.<br />

Resistant potato cultivars in rotation with susceptible cultivars<br />

and nonhosts considerably reduce the required length <strong>of</strong><br />

rotation.<br />

4) Co<strong>mb</strong>ining different control mcasures is necessary for<br />

keeping populations below damaging levels and for preventing<br />

establishment <strong>of</strong> nematodes in new areas. Key components <strong>of</strong><br />

nematode management are: extensive surveys to determine<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> cyst nematodes, soil fumigants to reduce<br />

nu<strong>mb</strong>ers <strong>of</strong> nematodes in the soil, resistant cultivars to prevent<br />

density increase, carbamate nematicides to suppress density<br />

increases, prohibition <strong>of</strong> potato seed production in known<br />

infested or exposed land, and regulation <strong>of</strong> reuseable containers<br />

and movement <strong>of</strong> farm machinery, top soil, and plant material.<br />

Selected References<br />

C111TWOOD. B.Gand E.M. BUIIRER. 1946. The life history<strong>of</strong>the<br />

golden nematode <strong>of</strong> potatoes, leterodera rostochiensis<br />

Wollenweber. under Long Islana. New York, conditions.<br />

Phytopathology 36:180-189.<br />

ENDO, 13.Y. 1971. Nematode-induced svncvtia (giant cells). Pages<br />

91-117 in: B. M. Zuckerman. W. F. Mai. and R. A. Rohde, eds.<br />

Plant Parasitic Nematodes, Vol. 2.Academic Press. New York. 347<br />

EVANS, K., .1. FRANCO. and M. M. de SCURRAII. 1975.<br />

)istribution <strong>of</strong> species <strong>of</strong> potato cyst-nematodes in South America.<br />

Nemnatologica 21:365-369.<br />

HOOPES, R.W. 1977. [he internal response <strong>of</strong> several resistant and<br />

susceptible potato clones to invasion by the potato cyst nematode<br />

IUniversity. I'ieroderarostochiensis 61 pp.<br />

Woilenweber. NIS thesis. Cornell<br />

MULVEY, R. II.. and A. R. STONE'.. 1976. Description <strong>of</strong> Punctodera<br />

maladorensis n. gen.. n. sp. (Nematoda: fleteroderidae) from<br />

Saskatchewan with lists <strong>of</strong> species and generic diagnosis <strong>of</strong><br />

(ilobodera In. rank). Ileterodera and Sarisodera. Can .1.Zool.<br />

54:772-785.<br />

SPEARS, .1. F. 1968. The Golden Nematode Handbook: Survey,