Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

should be planted on land with at least two to three years<br />

between potato crops, longer if volunteer potatoes are a problem.<br />

Lri'inia-free stocks may be rapidly rccontaminated. especially<br />

by L. caroto\vora var. carotovora under some conditions.<br />

5) Remove potato cull piles, discarded vegetables, and plant<br />

refuse to avoid inoculum sources from which insects transmit<br />

:rivinia spp.<br />

6) Frequently clean and disinfect seed cutting and hanaling<br />

equipment as well as planters, harvesters, and conveyers to<br />

eliminate contamination. This should be done at least between<br />

different seed lots.<br />

7) Avoid washing seed potatoes unless absolutely necessary,<br />

and exercise care<br />

to<br />

during<br />

seed tubers.Br<br />

handling operations to reduce damage<br />

t) Fertilie adequately with nitrogen.<br />

9) To reduce spread <strong>of</strong> bacteria to healthy plants, remove<br />

infected plants as soon as they appear.<br />

iectdt lati<br />

i Aoid eand<br />

lenticel infection,<br />

2) lilarvst tubers only when mature and only when soil-<br />

2) n~v 1laresttubrs henmatre nd n~v hensui tell-<br />

peratures are less than 20' C. Minimize mechanical damage to<br />

tubers during harvesting and handling.<br />

desiccation. 3) Protect harvested tubers from solar irradiation and<br />

4) Cool tubers to 10 ° C or lower as soon as possible after<br />

h4rest Cool tstoor atltomp t r as oo as possible ftery<br />

arvest and store at temperatures as low as possible (preferably<br />

.- 4.50 C). Good ventilation to keep tubers cool and to prevent<br />

accumulation <strong>of</strong> CO: and moisture films isespecially important.<br />

5) Avoid water films on tuber surfaces, eg, condensation that<br />

results from placing tubers with low pulp temperatures into<br />

storage with relative humidity above 90('.<br />

6) IDo not wash tubers before storage, and when washing<br />

them<br />

package<br />

before<br />

them<br />

marketing,<br />

in well-aerated<br />

dry<br />

containers,<br />

them as soon as possible and<br />

7) pse only clean water to wash potatoes. Contaminated<br />

holding tanks used for soaking potatoes almost assure s<strong>of</strong>t rot<br />

hdinction sed frshowater potato ing almose ue<br />

infection.<br />

ast<br />

Treat<br />

ont<br />

wash water with chlorine to reduce the amount<br />

Selected References<br />

BUCIIANAN. R.[-..and N.E.GIBBONS, eds. 1974. Bergey's Manual<br />

<strong>of</strong> )e:erminative Bacteriology.8thed. Pages337-338. Williamsand<br />

Wilkins. Baltimore, M). 1,268 pp.<br />

('IPITI.S. I)..and A. KEIMAN. 1974. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> selective media<br />

for isolation <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t rot bacteria from soil and plant tissue. Phytopathology<br />

64:468-475.<br />

I)elOIR. S.II.. and A. KF I.MAN. 1975. F.valuation <strong>of</strong> procedures for<br />

detection <strong>of</strong> pectolytic Erwinia spp. on potato tubers. Am. <strong>Potato</strong> J.<br />

52:117- 123.<br />

)el.INI)O, I... F.R. FRE-NCII,and A.KEIMAN. 1978. Erwiniaspp.<br />

pathogenic to potatoes in Peri. Am. <strong>Potato</strong> .1.55:383 (Abstr.).<br />

GRAHAM, I). C., and .1. . IIARI)IE. 1971. Prospects for control <strong>of</strong><br />

potato blackleg disease by the use <strong>of</strong> stem cuttings. Proc. Br.<br />

Insectic. Fungic. Conf.. 6th. pp. 219-224.<br />

IARRI SON. M. I).. C. E. QUINN. I. A. SE.L.S, and 1). C.<br />

(iGRAlAM. 1977. Waste potato dumps as sources <strong>of</strong> insects contaminated<br />

with s<strong>of</strong>t rot coliform bacteria in relation to<br />

recontamintion <strong>of</strong> pathogen-free potato stocks. p'otato Res.<br />

20:37--52.<br />

I.NI), B. M., and G;.M. WYATT. 1972. The effect <strong>of</strong> oxygen and<br />

carbon dioxide concentrations on bacterial s<strong>of</strong>t rot <strong>of</strong> potatoes. I.<br />

King Edward potatoes inoculated with Eroinia carotovora var.<br />

ltro ep tima . P o ta to R e s . 15 :17 4- 17 9 .<br />

MOIINA. ... , and M. I). IHARRISON. 198. The role <strong>of</strong> Erwinia<br />

rarotovora in the epidemiology <strong>of</strong> potato blackleg. II. The effect <strong>of</strong><br />

soil temperature on disease severity. Am. <strong>Potato</strong> .1.57:351-369.<br />

NII-IS-N, I.. W. 1946. Solar heat in relation to bacterial s<strong>of</strong>t rot <strong>of</strong><br />

early Irish potatoes. Am. <strong>Potato</strong> .1.23:41-57.<br />

NIEIlSEN. ILW. 1949. Ftu.oaritom seedpiece decay <strong>of</strong> potatoes in Idaho<br />

and its relation ti blackleg. Idaho Agric. Exp. Stn. Res. Bull. 15.<br />

31 pp.<br />

NIEI.SIEN, I. W. 1978. Eritiniaspecies in the lenticels <strong>of</strong> certified seed<br />

potatoes. Am. <strong>Potato</strong> .1.55:671-676.<br />

O'NEI I,., R., and C. LOG AN. 1975. A comiparison <strong>of</strong> various selective<br />

media for their efficiency in the diagnosis and enumeration <strong>of</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t<br />

rot coliform bacteria J. Appl. Bacteriol. 39:139-146.<br />

PEROMBELON, M. C. M. 1974. The role <strong>of</strong> the seed tuber in the<br />

contamination potato Res. 17:187-199. by Erwinia carotovora <strong>of</strong> potato crops in Scotland.<br />

STEWART., D.J. 1962. A selective-diagnostic medium forthe isolation<br />

<strong>of</strong> pectinolytic organismts in the Enterobacteriaceac. Nature<br />

195:1023.<br />

(Prepared by M. D. Harrison and L. W. Nielsen)-<br />

Brown Rot<br />

Brown rot, also known as bacterial wilt or southern bacterial<br />

w roas kn w asb ceilw tors uh nb cera<br />

wilt, affects potatoes in almost every region in the warmtemperate,<br />

semitropical, and tropical zones <strong>of</strong> the world and has<br />

been reported from relatively cool climates. It limits growing <strong>of</strong><br />

potatoes and other susceptible crops in parts <strong>of</strong> Asia, Africa,<br />

South and Central America. In the United States the disease<br />

occurs in the Southeast from Maryland to Florida. It has rarely<br />

occurred in the Southwest or Midwest and has not been confirmed<br />

west <strong>of</strong> the Rocky Mountains.<br />

Symptoms<br />

Field symptoms are wilting, stunting, and yellowing <strong>of</strong> the<br />

foliage. These may appear at any stage in the potato's growth.<br />

Wilting <strong>of</strong> leaves and collapse <strong>of</strong> stems may be severe in young,<br />

succulent plants <strong>of</strong> highly susceptible varieties. Initially, only<br />

one branch in a hill may show wilting. If disease development is<br />

rapid, all leaves <strong>of</strong> plants in a hill may wilt quickly without much<br />

change in color. Wilted leaves may fade to a pale green and<br />

finally turn brown without rolling <strong>of</strong>the leaflet edges as they dry<br />

(Plate 14). In young potato stems, dark narrow streaks,<br />

corresponding to infected vascular strands, become visible<br />

through the epidermis.<br />

Brown rot and ring rot have similar but distinguishable<br />

symptoms ('Fable 1). A valuable diagnostic sign <strong>of</strong> brown rot is<br />

glistening beads <strong>of</strong> a gray to brown slimy ooze on the infected<br />

xylem in stem cross sections. If the cut surfaces <strong>of</strong> a sectioned<br />

infected stem are placed in contact and then drawn apart slowly,<br />

fine strands <strong>of</strong> bacterial slime become visible and stretch ashort<br />

distance before breaking.<br />

To demonstrate bacteria in vascular tissue, a longitudinal<br />

section from a diseased stem can be placed s, that surface<br />

tension holds it to the side <strong>of</strong> a beaker <strong>of</strong> water and a short<br />

segment <strong>of</strong> the tissue projects below the water surface. Fine<br />

milky white strands, composed <strong>of</strong> masses <strong>of</strong> bacteria in extracellular<br />

slime, stream down from the cut ends <strong>of</strong> xylem vessels<br />

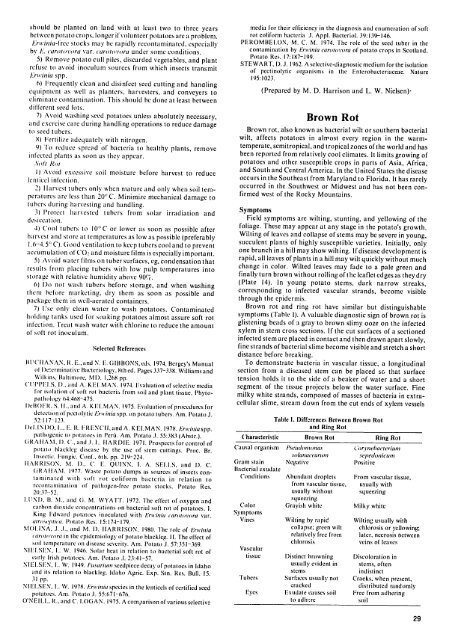

Table I. Differences Between Brown Rot<br />

and Ring Rot<br />

Characteristic Brown Rot Ring Rot<br />

Gram GrOham stain staearnn<br />

Bacterial exudate<br />

Conditions<br />

seodoaoorws L oneln t<br />

Negative Positive sie onict m<br />

Abundant droplets From vascular tissue,<br />

from vascular tissue, usually with<br />

usuallywithout squeezing<br />

u squeezing<br />

Color<br />

Symptoms<br />

Vines<br />

V i n e s<br />

Grayish hite Milky white<br />

Wilting by rapid Wilting usually with<br />

g r e e n w ilt i u s u a ll owi<br />

collapse; green wilt<br />

free from<br />

chlorosis<br />

chlorosis or yellowing;<br />

later, necrosis between<br />

veins <strong>of</strong> leaves<br />

Vascular<br />

tissue<br />

Tubers<br />

Eyes<br />

uistinct brovning<br />

usually evident in<br />

stems<br />

Surfaces usially not<br />

cracked<br />

Eixudate causes soil<br />

to adh,:re<br />

Discoloration in<br />

stems, <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

indistinct<br />

Cracks, when present,<br />

distributed randomly<br />

Free from adhering<br />

soil<br />

29