Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

Compendium of Potato Diseases - (PDF, 101 mb) - USAID

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

have been demonstrated, including tomato, D. stranionium,<br />

and a Physalis species. D. stramoniutm also seems to be a<br />

reservoir for the virus in the Andean region, where it is a<br />

common weed. No evidence indicates that hosts other than<br />

potato act as a virus reservoir in the temperate regions.<br />

Nonsolanaceous hosts are found in the Amaranthaceae.<br />

Tuber Indexing<br />

Symptom development in eye sprouts can be used to index for<br />

virus infection in postharvest glasshouse tests. The <strong>of</strong>ten-used<br />

Igel-Lange test (deep blue staining <strong>of</strong> phloem sieve tubes after 10<br />

rin in Il " aqueous resorcin blue) is based on increased deposits<br />

<strong>of</strong> callose in the phloem (Fig. 73C). Neither method is<br />

completely reliable because symptoms are not always produced<br />

and because callose, which is not always observed in infected<br />

tubers, may also be found in healthy tubers.<br />

Electron microscope techniques alone are unreliable because<br />

<strong>of</strong> the low concentration <strong>of</strong> virus particles in infected plants. In<br />

co<strong>mb</strong>ination with serological techniques, electron microscopy is<br />

efficient.<br />

The recent application <strong>of</strong> EI.ISA to detect the virus in<br />

tuber and other plant material has resulted in improved<br />

indexing techniques. A reliable method, although laborious to<br />

perform, involves aphid transmission tests on eye sprouts, using<br />

indicator plants such as P..1loridana.<br />

A technique in which leaves, stems, and small pieces <strong>of</strong> tuber<br />

are grafted to D.stramonium isnow used on a large scale in seed<br />

multiplication work in Brazil. This method is considered to be<br />

less time-consuming than that using aphids and P.floridana.<br />

Control<br />

I) Breeding resistant cultivars has met only limited success.<br />

Resistance is determined by many genes with additive effects<br />

and can only gradually be built up. Varying levels <strong>of</strong> resistance<br />

are found in some seedlings. Crossing <strong>of</strong> unrelated resistant<br />

parents may result in a higher proportion <strong>of</strong> resistant <strong>of</strong>fspring<br />

than does inbreeding. Resistance isalso found in progenies from<br />

S. de'nissun, S. and(igena, S. acaisle, S. chacoense, S.<br />

stololnferunn, and S. etuherosuim.<br />

2) Disease-free seed tubers are essential for maximum<br />

production. Seed tubers with a low percentage <strong>of</strong> infection can<br />

be produced in areas where sources <strong>of</strong> virus are limited and<br />

aphids appear late in the season. Seed plots should be harvested<br />

as early as possible, compatible with reasonable yields, to avoid<br />

late season aphid transmission. Dates for lifting may be<br />

determined by the nu<strong>mb</strong>er <strong>of</strong> aphids caught in yellow traps or<br />

assessed by other methods.<br />

3) To minimi/e infection, measures such as clonal selection,<br />

early planting <strong>of</strong> virus-free tubers (from seed certification<br />

programs), and early lifting and roguing <strong>of</strong> infected plants and<br />

killing or removal <strong>of</strong> volunteer plants in and around the field can<br />

be Lused.<br />

4) Aphids should be controlled by toxic sprays or systemic<br />

insecticides. Application <strong>of</strong> granulated systemic insecticides has<br />

been successful in certain cases. Spread cannot be controlled by<br />

oil sprays.<br />

5)Tubers may be freed <strong>of</strong> the virus by heating, e.g., 25 days at<br />

37.50 C.<br />

Selected References<br />

BACON, 0. G., V. E. BURTON, D. .. McLEAN. R.H. JAMES, W.<br />

t). RII.EY, K.G.BAGHIOTT, and M.G.KINSEY. 1976. Control <strong>of</strong><br />

the green peach aphid and its effect on the incidence <strong>of</strong> potato leaf roll<br />

virus. J. Econ. Entomol. 69:410-414.<br />

CHIKO, A. W.. and .1.W. GUTHRIE. 1969. An hypothesis for<br />

selection <strong>of</strong> strains <strong>of</strong> potato leafroll virus by passage through<br />

Phrsalisfloridana.Am. <strong>Potato</strong> .1.46:155-167.<br />

CUIPERIINO. F. I1.. and A. S. COSTA. 1967. l)eterminaciodo virus<br />

do enrolamento em hastas velhas de batalal para sementes. Bragantia<br />

26:181-186.<br />

l)AVI)SON.l-.M. W. 1973. Assessing resistance to leafroll in potato<br />

seedlings. <strong>Potato</strong> Res. 16:99-108.<br />

de BOKX. .1.A. 1967. [he callose test for the detection <strong>of</strong> leafroll virus<br />

I. .,.T. .<br />

:. ,.. " -<br />

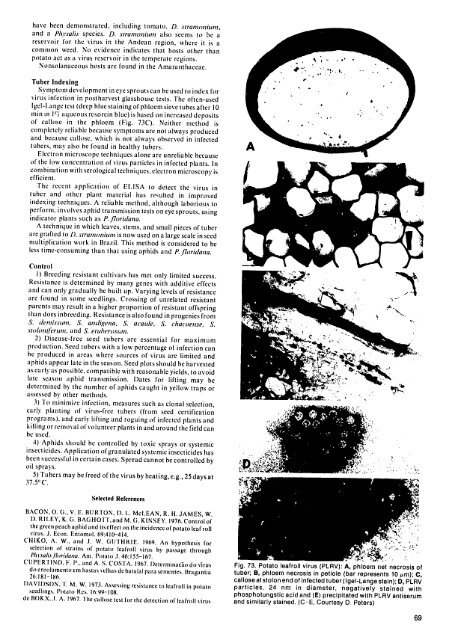

Fig. 73. <strong>Potato</strong> leafroll virus (PLRV): A, phloem net necrosis <strong>of</strong><br />

tuber; B, phloem necrosis in petiole (bar represents 10 pm); C,<br />

callose at stolon end <strong>of</strong> infected tuber (Igel-Lange stain); D,PLRV<br />

particles, 24 nm in diameter, negatively stained with<br />

phosphotungstic acid and (E)precipitated with PLRV antiserum<br />

and similarly stained. (C-E. Courtesy D. Peters)<br />

0<br />

69