world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

invasive malignant. Malignant germ cell<br />

tumours are uncommon.<br />

A majority of familial ovarian <strong>cancer</strong> seems to<br />

be due to mutations in the BRCA1 and<br />

BRCA2 genes, which are also associated with<br />

a predisposition for breast <strong>cancer</strong> (Genetic<br />

susceptibility, p71), (although BRCA1 is also<br />

mutated in a minority of sporadic tumours<br />

[18]). Familial syndromes linked to increased<br />

risk of ovarian <strong>cancer</strong> include breast-ovarian<br />

<strong>cancer</strong> syndrome, rare families who present<br />

with ovarian <strong>cancer</strong>s only and Lynch type II<br />

syndrome, which is characterized by inheri-<br />

MULTICULTURAL ISSUES<br />

Although incidence of <strong>cancer</strong> is often<br />

recorded with reference to national or otherwise<br />

large populations, the disease burden<br />

is rarely distributed uniformly across<br />

such groupings. This becomes apparent<br />

when consideration is given to specific<br />

minority groups within a wider community.<br />

A number of variables may contribute<br />

to such an outcome. One such variable,<br />

genetic make-up, is not amenable to intervention<br />

but nonetheless may have an<br />

impact. For example, there are large<br />

racial/ethnic differences in prostate <strong>cancer</strong><br />

risk, with high rates of incidence in<br />

African-Americans, which may be partly<br />

related to genetic differences in hormone<br />

metabolism (Farkas A et al., Ethn Dis, 10:<br />

69-75, 2000). However, mutations which<br />

confer susceptibility to <strong>cancer</strong> may be carried<br />

by individuals from any and all ethnic<br />

groups (Neuhausen SL, Cancer, 86: 2575-<br />

82, 1999).<br />

In many instances, there are clear indications<br />

that in some ethnic minorities, immigrant<br />

populations and the poor and disadvantaged,<br />

the burden of <strong>cancer</strong> is greater<br />

than that of the general population (e.g.<br />

Kogevinas M et al., Social inequalities and<br />

<strong>cancer</strong>, Lyon, IARCPress, 1997). In the<br />

USA, for example, whilst incidence and<br />

mortality rates for some <strong>cancer</strong>s have<br />

decreased in the population overall, rates<br />

have increased in some ethnic minority<br />

groups. The mortality rate for <strong>cancer</strong> at all<br />

tance of nonpolyposis colorectal <strong>cancer</strong><br />

(Colorectal <strong>cancer</strong>, p198), endometrial <strong>cancer</strong><br />

and ovarian <strong>cancer</strong> and is linked to mutations<br />

in DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2,<br />

MLH1, PMS1 and PMS2 (Carcinogen activation<br />

and DNA repair, p89)[18,19]. Prophylactic<br />

oophorectomy is a potential option for genetically<br />

high-risk women.<br />

The ERBB2 (HER-2/neu) oncogene is overexpressed<br />

in about 30% of ovarian tumours, as is<br />

C-MYC [21]. KRAS mutational activation is also<br />

implicated in ovarian <strong>cancer</strong>. p53 mutations<br />

have been found in 50% of cases.<br />

sites in white people in 1990-96 was 167.5<br />

per 100,000 whilst in the black population it<br />

was 223.4. The reasons for such differences<br />

are likely to be complex and multifactorial.<br />

Environmental/behavioural factors may differ<br />

between ethnic/cultural groups. For<br />

instance, the diet to which some migrant<br />

populations are accustomed (e.g. small<br />

quantities of red meat, large quantities of<br />

fruit and vegetables) may be protective in<br />

relation to risk of colorectal <strong>cancer</strong>, but risk<br />

increases with the adoption of a Western<br />

diet (e.g. Santani DL, J Assoc Acad Minor<br />

Phys, 10: 68-76, 1999).<br />

Timely visits to a medical practitioner and<br />

participation in screening programmes are<br />

critical for early detection and initiation of<br />

treatment. Language may be a barrier to<br />

understanding health issues. Women from<br />

certain ethnic and racial minorities are less<br />

likely to take up invitations to participate in<br />

breast or cervical screening programmes.<br />

This may be partly attributable to the novelty<br />

of the concept of preventive health, unfamiliarity<br />

with the disease, or with the health<br />

system, as well as modesty and<br />

religious/cultural barriers. Women of lower<br />

socioeconomic status tend to present with<br />

a more advanced stage of breast <strong>cancer</strong><br />

than women of higher socioeconomic status.<br />

African-American, Hispanic, American<br />

Indian and Hawaiian women also tend to<br />

present with a more advanced stage of<br />

breast <strong>cancer</strong> than white women (e.g.<br />

Hunter CP, Cancer, 88: 1193-202, 2000). In<br />

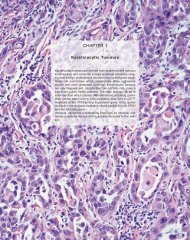

Fig. 5.70 Histopathology of a well-differentiated,<br />

mucus-secreting, endometrial-like adenocarcinoma<br />

of the ovary.<br />

the USA, women who do not subscribe to<br />

private health insurance are less likely to<br />

undergo screening for breast, cervical and<br />

colorectal <strong>cancer</strong>s (Hsia J et al., Prev Med,<br />

31: 261-70, 2000). Such differences involving<br />

increased incidence provide an opportunity<br />

for strategic action.<br />

Treatment and its outcome may also be<br />

affected by ethnic and social differences.<br />

For example, the way that pain is perceived<br />

and dealt with is influenced by the<br />

ethnocultural background of the patient<br />

(Gordon C, Nurse Pract Forum, 8: 5-13,<br />

1997). Ethical dilemmas can develop in<br />

multicultural settings due to differing cultural<br />

beliefs and practices. More research<br />

into the relationship between ethnicity<br />

and accessibility of medical care, patient<br />

support, survival, and quality of life is<br />

needed (Meyerowitz BE, Psychol Bull, 123:<br />

47-70, 1998).<br />

Recognition of multicultural issues is<br />

becoming more widespread. The NCI has<br />

launched an initiative to investigate the<br />

reasons for disparities in <strong>cancer</strong> in minority<br />

populations (the “Special Populations<br />

Networks for Cancer Awareness Research<br />

and Training”, Mitka M, JAMA, 283: 2092-<br />

3, 2000). Many areas have units designed<br />

to improve equality of access to health<br />

care (e.g. NSW Health Multicultural<br />

Health Communication Service,<br />

http://www.health.nsw.gov.au).<br />

Cancers of the female reproductive tract<br />

221