world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

after cessation of use. Interestingly, however,<br />

use of sequential oral contraceptives,<br />

containing progestogens only in the<br />

first five days of a cycle, is associated<br />

with an increased risk of endometrial <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

For ovarian <strong>cancer</strong>, risk is reduced in<br />

women using combined oral contraceptives,<br />

the reduction being about 50% for<br />

women who have used the preparations<br />

for at least five years (Table 2.22). Again,<br />

this reduction in risk persists for at least<br />

10-15 years after cessation of use. It has<br />

also been suggested that long-term use of<br />

oral contraceptives (more than five years)<br />

could be a cofactor that increases risk of<br />

cervical carcinoma in women who are<br />

infected with human papillomavirus [9].<br />

Postmenopausal hormone replacement<br />

therapy<br />

Clinical use of estrogen to treat the symptoms<br />

of menopause (estrogen replacement<br />

therapy or hormone replacement therapy)<br />

began in the 1930s, and became widespread<br />

in the 1960s. Nowadays, up to 35%<br />

of menopausal women in the USA and<br />

many European countries have used<br />

replacement therapy at least for some period.<br />

The doses of oral estrogen prescribed<br />

decreased over the period 1975-83 and the<br />

use of injectable estrogens for estrogen<br />

replacement therapy has also diminished.<br />

On the other hand, the use of transdermally<br />

administered estrogens has increased<br />

progressively to about 15% of all estrogen<br />

replacement therapy prescriptions in some<br />

countries. In the 1960s, some clinicians,<br />

especially in Europe, started prescribing<br />

combined estrogen-progestogen therapy,<br />

primarily for better control of uterine bleeding.<br />

The tendency to prescribe combined<br />

estrogen-progestogen hormonal replacement<br />

therapy was strengthened when first<br />

epidemiological studies showed an<br />

increase in endometrial <strong>cancer</strong> risk in<br />

women using estrogens alone.<br />

A small increase in breast <strong>cancer</strong> risk is<br />

correlated with longer duration of estrogen<br />

replacement therapy use (five years<br />

or more) in current and recent users [8].<br />

The increase seems to cease several years<br />

after use has stopped. There appears to<br />

be no material difference in breast <strong>cancer</strong><br />

risk between long-term users of all hor-<br />

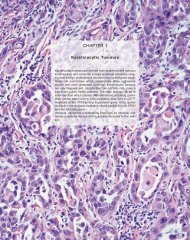

Fig. 2.71 Estimated risk of breast <strong>cancer</strong> by time since last use of combined oral contraceptives, relative<br />

to never-users. Data adjusted by age at diagnosis, parity, age at first birth and age at which risk of conception<br />

ceased. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence interval.<br />

mone replacement therapy and users of<br />

estrogens alone. Nevertheless, one large<br />

cohort study and a large case-control<br />

study have provided strong evidence for a<br />

greater increase in breast <strong>cancer</strong> risk in<br />

women using hormone replacement therapy<br />

than in women using estrogens alone<br />

[10,11].<br />

For endometrial <strong>cancer</strong>, there is an<br />

increase in risk among women using estrogen<br />

replacement therapy, the risk increasing<br />

further with longer duration of use [8].<br />

In contrast, women using hormone<br />

replacement therapy have only a mild<br />

increase in risk compared to women who<br />

have never used any postmenopausal hormone<br />

replacement and this increase is<br />

much smaller than that of women who<br />

used estrogens alone. There seems to be<br />

no relationship between risk of ovarian<br />

<strong>cancer</strong> and postmenopausal estrogen use,<br />

while data on ovarian <strong>cancer</strong> risk in relation<br />

to hormone replacement therapy use<br />

are too scarce to evaluate.<br />

Prostate <strong>cancer</strong><br />

Normal growth and functioning of prostatic<br />

tissue is under the control of testosterone<br />

through conversion to dihydroxytestosterone<br />

[12]. Dihydroxytestosterone<br />

is bound to the androgen receptor, which<br />

translocates the hormone to the nucleus.<br />

There have been conflicting findings as to<br />

whether patients with prostate <strong>cancer</strong><br />

have higher levels of serum testosterone<br />

than disease-free controls. Diminution of<br />

testosterone production, either through<br />

estrogen administration, orchidectomy or<br />

treatment with luteinizing hormonereleasing<br />

hormone agonists, is used to<br />

manage disseminated prostate <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

Mechanisms of tumorigenesis<br />

Breast <strong>cancer</strong><br />

The role of endogenous hormones in<br />

breast <strong>cancer</strong> development suggests the<br />

“estrogen excess” hypothesis, which stipulates<br />

that risk depends directly on<br />

breast tissue exposure to estrogens.<br />

Estrogens increase breast cell proliferation<br />

and inhibit apoptosis in vitro, and in<br />

experimental animals cause increased<br />

rates of tumour development when estrogens<br />

are administered. Furthermore, this<br />

theory is consistent with epidemiological<br />

studies [4,15] showing an increase in<br />

breast <strong>cancer</strong> risk in postmenopausal<br />

women who have low circulating sex hormone-binding<br />

globulin and elevated total<br />

and bioavailable estradiol.<br />

The “estrogen-plus-progestogen” hypothesis<br />

[15,16] postulates that, compared<br />

Reproductive factors and hormones<br />

77