world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A B<br />

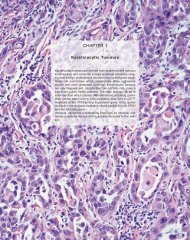

Fig. 5.113 Acute myeloid leukaemia; agranular myeloblasts (A) and granulated myeloblasts (B).<br />

bone marrow and lymph nodes, admixed<br />

with prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts,<br />

usually expressing CD5 and<br />

CD23 surface antigen [5]. Chronic lymphocytic<br />

leukaemia [10] is a heterogeneous<br />

disease which can occur in an indolent<br />

form with very little progression, whilst at<br />

the other extreme it may present with<br />

severe bone marrow failure and a poor<br />

prognosis.<br />

Management<br />

Remarkable progress in the understanding<br />

and treatment of leukaemia has been<br />

made in the past century [11]. In the first<br />

instance, this generalization refers specifically<br />

to paediatric disease. Prior to 1960,<br />

leukaemia was the leading cause of death<br />

Fig. 5.115 Spectral karyotyping of a chronic myeloid leukaemia case reveals<br />

a variant Philadelphia chromosome involving translocations between chromosomes<br />

3, 9, 12 and 22. Secondary changes involving chromosomes 1, 5,<br />

8, 18 and X are also seen, indicating advanced disease.<br />

from malignancy in children under 15; currently,<br />

more than 80% of children with<br />

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia can be<br />

cured with chemotherapy [12]. Treatment<br />

involves induction of remission with combinations<br />

of agents (such as vincristine,<br />

daunorubicin, cytarabine [cytosine arabinoside],<br />

L-asparaginase, 6-thioguanine,<br />

and steroids) followed by consolidation,<br />

maintenance and post-remission intensification<br />

therapy to eradicate residual<br />

leukaemic blast cells, aiming at cure.<br />

Intensive supportive care throughout treatment<br />

is of major importance. Prophylactic<br />

treatment with intrathecal methotrexate<br />

injections, with or without craniospinal<br />

irradiation, is mandatory in the management<br />

of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia to<br />

Fig. 5.114 A bone marrow biopsy of acute promyelocytic<br />

leukaemia. Abnormal promyelocytes have<br />

abundant hypergranulated cytoplasm. The nuclei<br />

are generally round to oval, several being irregular<br />

and invaginated.<br />

prevent possible involvement of or relapse<br />

in the central nervous system. The use of<br />

radiotherapy is limited because of the<br />

potential long-term side-effects, particularly<br />

effects on the growth of the young child<br />

and the risk of second malignancies. The<br />

adult form of acute lymphoblastic<br />

leukaemia is also susceptible to therapy<br />

and can be cured, (although not as readily<br />

as childhood leukaemia), with intensive<br />

combination therapy [13].<br />

For acute leukaemia in adults, the initial<br />

aim of management is to stabilize the<br />

patient with supportive measures to counteract<br />

bone marrow failure which leads to<br />

anaemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia.<br />

Most patients with leukaemia<br />

who die in the first three weeks of diagno-<br />

Fig. 5.116 Acute promyelocytic leukaemia cells with t(15;17)(q22;q12)<br />

translocation. Fluorescence in situ hybridization with probes for PML (red)<br />

and RARα (green) demonstrates the presence of a PML/RARα fusion protein<br />

(overlapping of red and green = yellow signal) resulting from the breakage<br />

and fusion of these chromosome bands.<br />

Leukaemia<br />

245