world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

world cancer report - iarc

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Fig. 2.54 The age-adjusted mortality rate for gastric <strong>cancer</strong> increases with increasing salt consumption,<br />

as measured by 24-hour urine sodium excretion, in selected regions of Japan.<br />

S. Tsugane et al. (1991) Cancer Causes Control, 2:165-8.<br />

a protective effect of animal protein (and<br />

meat) while some studies on colorectal<br />

<strong>cancer</strong> found an increased risk for animal<br />

protein (and meat).<br />

Results on carbohydrates are difficult to<br />

interpret because of inconsistencies in the<br />

way different food composition tables<br />

subdivide total carbohydrates into subfractions<br />

that have very different physiological<br />

and metabolic effects and which<br />

may affect carcinogenesis in opposite<br />

ways. The only pattern that seems to<br />

emerge so far is that consumption of simple<br />

sugars (mono- and disaccharides) may<br />

be associated with increased colorectal<br />

<strong>cancer</strong> risk, while consumption of complex<br />

polysaccharides, non-starch polysaccharides<br />

and/or fibre (partially overlapping<br />

categories based on different chemical<br />

and physiological definitions) is associated<br />

with lower <strong>cancer</strong> risk. Other less<br />

consistent findings suggest that a diet<br />

excessively rich in starchy foods (mainly<br />

beans, flour products or simple sugars)<br />

but also poor in fruit and vegetables, may<br />

be associated with increased gastric <strong>cancer</strong><br />

risk.<br />

The hypothesis that high fat intake is a<br />

major <strong>cancer</strong> risk factor of the Westernstyle<br />

diet has been at the centre of most<br />

64 The causes of <strong>cancer</strong><br />

epidemiological and laboratory experimental<br />

studies. The results are, however,<br />

far from clear and definitive. The positive<br />

association with breast <strong>cancer</strong> risk suggested<br />

by international correlation studies<br />

and supported by most case-control studies<br />

was not found in the majority of the<br />

prospective cohort studies conducted so<br />

far. Very few studies have investigated the<br />

effect of the balance between different<br />

types of fats, specifically as containing<br />

poly-unsaturated, mono-unsaturated and<br />

saturated fatty acids, on <strong>cancer</strong> risk in<br />

humans. The only moderately consistent<br />

result seems to be the positive association<br />

between consumption of fats of animal<br />

origin (except for fish) and risk of<br />

colorectal <strong>cancer</strong>. Additionally, olive oil in<br />

the context of the Mediterranean dietary<br />

tradition is associated with a reduced risk<br />

of <strong>cancer</strong> [10].<br />

Food additives<br />

Food additives are chemicals added to<br />

food for the purpose of preservation or to<br />

enhance flavour, texture or colour. Less<br />

than comprehensive toxicological data are<br />

available for most additives, although<br />

some have been tested for mutagenic or<br />

carcinogenic activity. In in vitro assay sys-<br />

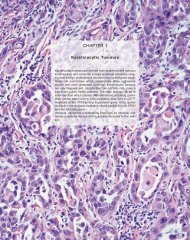

Fig. 2.55 Consumption of salted fish (such as this<br />

salted cod) is associated with an increased risk of<br />

stomach <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

tems, some additives, such as dietary phenolics,<br />

have both mutagenic and antimutagenic<br />

effects [11]. In the past, some<br />

chemicals were employed as food additives<br />

before their carcinogenicity in animals<br />

was discovered, e.g. the colouring<br />

agent “butter yellow” (dimethylaminoazobenzene)<br />

and, in Japan, the preservative<br />

AF2 (2-(2-furyl)-3-(5-nitro-2-furyl)<br />

acrylamide). Saccharin and its salts have<br />

been used as sweeteners for nearly a century.<br />

Although some animal bioassays<br />

have revealed an increased incidence of<br />

urinary bladder <strong>cancer</strong>, there is inadequate<br />

evidence for carcinogenicity of saccharin<br />

in humans [12]. The proportion of<br />

Fig. 2.56 Saccharin with a warning label recognizing<br />

a possible role in <strong>cancer</strong> causation.