Contribution of Forestry to Poverty Alleviation - APFNet

Contribution of Forestry to Poverty Alleviation - APFNet

Contribution of Forestry to Poverty Alleviation - APFNet

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Small-holder tree farms/private land tree plantations<br />

Smallholder tree farming in upland areas are mostly under the tenure <strong>of</strong> Certificate <strong>of</strong> Stewardship<br />

Contract (CSC) which was popularized in the 1980s. This was seen as an economic empowerment<br />

program where farmers were encouraged <strong>to</strong> engage in the tree farming business. With the advent<br />

<strong>of</strong> CBFM, many CSC holders opted <strong>to</strong> join POs, retaining their individual property rights over the<br />

original CSC area. On the other hand, tree farming in private lands is popular in Mindanao, particularly<br />

in the Agusan del Sur area. Falcata, gmelina, and rubber are the most popular tree crops planted.<br />

Tree farming provides plenty <strong>of</strong> livelihood opportunities for local people, from seedling production <strong>to</strong><br />

planting, maintenance, harvesting, and marketing activities that entail hiring <strong>of</strong> local labor. Even the<br />

communities dependent on traditional forestry benefit from employment in these tree farms as part<br />

time labor during peak labor seasons <strong>of</strong> maintenance and harvesting.<br />

Industrial <strong>Forestry</strong><br />

The wood-based industry was once a pillar <strong>of</strong> the national economy contributing around 5% <strong>to</strong> the<br />

country’s gross national product (GNP) in the 1970s through forest charges, export earnings, and<br />

generation <strong>of</strong> employment. Table IX.5 shows the country’s GNP and gross value added (GVA) in forestry<br />

as well as the share <strong>of</strong> forestry <strong>to</strong> the GNP at constant prices. The GVA and percentage share <strong>of</strong> forestry<br />

in the GNP declined since the 1970s. The percentage share <strong>of</strong> forestry in GNP dropped from 2.11% in<br />

1981-1985 <strong>to</strong> 0.83% in 1990, and further dropped <strong>to</strong> only 0.06 % in 2001-2005 at current prices. This<br />

decreasing importance <strong>of</strong> forestry as an economic sec<strong>to</strong>r in the economy as reflected in the GVA share<br />

is somehow due <strong>to</strong> the continued strong growth in other economic sec<strong>to</strong>rs and the shrinking recorded<br />

production in the sec<strong>to</strong>r, especially in the logging sec<strong>to</strong>r. From a <strong>to</strong>tal round log production <strong>of</strong> around<br />

11 million cu m in the mid-1970s, <strong>to</strong>tal production shrunk <strong>to</strong> 1.4 million cu m in 2009 (FMB 2010).<br />

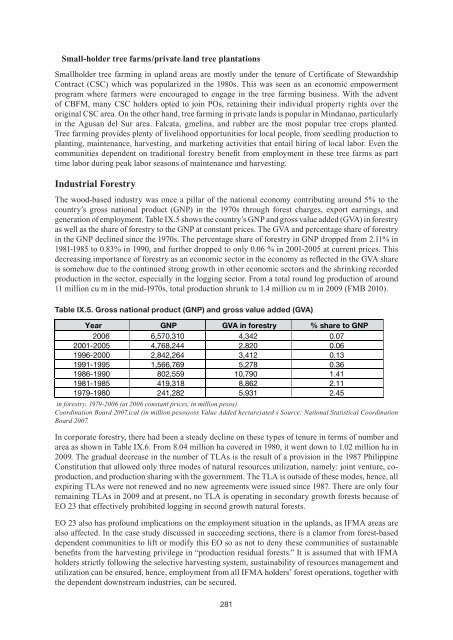

Table IX.5. Gross national product (GNP) and gross value added (GVA)<br />

Year GNP GVA in forestry % share <strong>to</strong> GNP<br />

2006 6,570,310 4,342 0.07<br />

2001-2005 4,768,244 2,820 0.06<br />

1996-2000 2,842,264 3,412 0.13<br />

1991-1995 1,566,769 5,278 0.36<br />

1986-1990 802,559 10,790 1.41<br />

1981-1985 419,318 8,862 2.11<br />

1979-1980 241,282 5,931 2.45<br />

in forestry, 1979-2006 (at 2006 constant prices, in million pesos)<br />

Coordination Board 2007.ical (in million pesos)oss Value Added hectare)ated s Source: National Statistical Coordination<br />

Board 2007.<br />

In corporate forestry, there had been a steady decline on these types <strong>of</strong> tenure in terms <strong>of</strong> number and<br />

area as shown in Table IX.6. From 8.04 million ha covered in 1980, it went down <strong>to</strong> 1.02 million ha in<br />

2009. The gradual decrease in the number <strong>of</strong> TLAs is the result <strong>of</strong> a provision in the 1987 Philippine<br />

Constitution that allowed only three modes <strong>of</strong> natural resources utilization, namely: joint venture, coproduction,<br />

and production sharing with the government. The TLA is outside <strong>of</strong> these modes, hence, all<br />

expiring TLAs were not renewed and no new agreements were issued since 1987. There are only four<br />

remaining TLAs in 2009 and at present, no TLA is operating in secondary growth forests because <strong>of</strong><br />

EO 23 that effectively prohibited logging in second growth natural forests.<br />

EO 23 also has pr<strong>of</strong>ound implications on the employment situation in the uplands, as IFMA areas are<br />

also affected. In the case study discussed in succeeding sections, there is a clamor from forest-based<br />

dependent communities <strong>to</strong> lift or modify this EO so as not <strong>to</strong> deny these communities <strong>of</strong> sustainable<br />

benefits from the harvesting privilege in “production residual forests.” It is assumed that with IFMA<br />

holders strictly following the selective harvesting system, sustainability <strong>of</strong> resources management and<br />

utilization can be ensured, hence, employment from all IFMA holders’ forest operations, <strong>to</strong>gether with<br />

the dependent downstream industries, can be secured.<br />

281