- Page 4 and 5:

Fullerton, Californiawww.lightandma

- Page 7 and 8:

Contents0 Introduction and Review0.

- Page 9 and 10:

5.5 More About Heat Engines . . . .

- Page 11 and 12:

669.11.3 Magnetic Fields by Ampère

- Page 13 and 14:

The Mars Climate Orbiter is prepare

- Page 15:

temperatures and with many combinat

- Page 19 and 20:

idence that quarks have smaller par

- Page 21 and 22:

give clearer explanations.Finally,

- Page 23 and 24:

It can also be handy to have a rela

- Page 25 and 26:

The prefix centi-, meaning 10 −2

- Page 27 and 28:

goes like this:V = 1 3 Ah[1]A = πr

- Page 29 and 30:

the notation 10 0 to stand for one,

- Page 32 and 33:

calculation, 5.04 cm, was really no

- Page 34 and 35:

0.2 Scaling and Order-of-Magnitude

- Page 36 and 37:

to many times your own height. The

- Page 38 and 39:

g / 1. This plank is as long as it

- Page 40 and 41:

the front panels of the three violi

- Page 42 and 43:

Correct solution #4: The area of a

- Page 44 and 45:

here?” The scientific Mr. Spock w

- Page 46 and 47:

1. Don’t even attempt more than o

- Page 48 and 49:

Problem 10.mean, however, is define

- Page 50 and 51:

(d) Find the person’s acceleratio

- Page 52 and 53:

Albert Einstein, and his moustache,

- Page 54 and 55:

54 Chapter 0 Introduction and Revie

- Page 56 and 57:

a / Portrait of Monsieur Lavoisiera

- Page 58 and 59:

1.1.1 Problem-solving techniquesHow

- Page 60 and 61:

∆m = 0, where m is the total mass

- Page 62 and 63:

different substances will have diff

- Page 64 and 65:

c / Left: In a frame of referenceth

- Page 66 and 67:

f / Discussion question B.(discusse

- Page 68 and 69:

Self-check D.since the derivative o

- Page 70 and 71:

ProblemsThe symbols √ , , etc. ar

- Page 72 and 73:

difficult? ⊲ Solution, p. 932Key

- Page 74 and 75:

Heat energy can be convertedto ligh

- Page 76 and 77:

a new form of invisible “mystery

- Page 78 and 79:

f / A realistic drawing of Joule’

- Page 80 and 81:

numbers. With a purely numerical ap

- Page 82 and 83:

of gravity doesn’t change much if

- Page 84 and 85:

field. If the plane can start from

- Page 86 and 87:

m / Discussion question C.n / A hyd

- Page 88 and 89:

88 Chapter 2 Conservation of Energy

- Page 90 and 91:

A car drives over a cliff.new frame

- Page 92 and 93:

How long does it take to move 1 met

- Page 94 and 95:

a / Approximations to thebrachistoc

- Page 96 and 97:

a / An ellipse is circle that hasbe

- Page 98 and 99:

to deduce the general equation for

- Page 100 and 101:

to the mass of the object that inte

- Page 102 and 103:

The minimum velocity required for t

- Page 104 and 105:

and since sin θ dθ occurs in the

- Page 106 and 107:

that is deeper than r. Under the as

- Page 108 and 109:

2.3.6 ⋆ Evidence for repulsive gr

- Page 110 and 111:

a / A vivid demonstration thatheat

- Page 112 and 113:

ture. This is a very good question,

- Page 114 and 115:

Three functions with thesame curvat

- Page 116 and 117:

This looks like a cosine function,

- Page 118 and 119:

ProblemsThe symbols √ , , etc. ar

- Page 120 and 121:

Problem 16.13 Anya and Ivan lean ov

- Page 122 and 123:

Problem 27.then we’d have U/m =

- Page 124 and 125:

37 Two springs with spring constant

- Page 126 and 127:

ExercisesExercise 2A: Reasoning wit

- Page 128 and 129:

128 Chapter 2 Conservation of Energ

- Page 130 and 131:

3.1 Momentum In One Dimensiona / Sy

- Page 132 and 133:

eing to the right. The initial mome

- Page 134 and 135:

3.1.3 Momentum compared to kinetic

- Page 136 and 137:

3.1.4 Collisions in one dimensiong

- Page 138 and 139:

could never do that again in a mill

- Page 140 and 141:

i / The highjumper’s body passeso

- Page 142 and 143:

where x 1 is the mass of the first

- Page 144 and 145:

3.1.6 The center of mass frame of r

- Page 146 and 147:

The airbag increases ∆tso as to r

- Page 148 and 149:

d / Two magnets exert forceson each

- Page 150 and 151:

x (m) t (s)10 1.8420 2.8630 3.8040

- Page 152 and 153:

3.2.4 Forces between solidsConserva

- Page 154 and 155:

Maximum acceleration of a car examp

- Page 156 and 157:

Discussion QuestionA Criticize the

- Page 158 and 159:

C A pool ball is rebounding from th

- Page 160 and 161:

forces, as if the hand were a pair

- Page 162 and 163:

This may not sound like an impressi

- Page 164 and 165:

stroke are both executed in straigh

- Page 166 and 167:

Accelerating a cart example 35If yo

- Page 168 and 169:

w / A wedge.x / Archimedes’ screw

- Page 170 and 171:

As in the preceding example, we hav

- Page 172 and 173:

that have the same frequency is a s

- Page 174 and 175:

around until I got this result, sin

- Page 176 and 177:

quality factor, Q, is defined as Q

- Page 178 and 179:

ight direction to add energy to the

- Page 180 and 181:

i / Example 45: a viola withouta mu

- Page 182 and 183:

Collapse of the Nimitz Freeway exam

- Page 184 and 185:

end up canceling out, however:Q =

- Page 186 and 187:

186 Chapter 3 Conservation of Momen

- Page 188 and 189:

c / Bullets are dropped and shot at

- Page 190 and 191:

the asteroid’s energy and boostin

- Page 192 and 193:

coordinate axes. Even though ∆x,

- Page 194 and 195:

of the three components,∆p x = 0

- Page 196 and 197:

A useless vector operation example

- Page 198 and 199:

Solving for the unknowns gives∆x

- Page 200 and 201:

o / Example 64.p / Adding vectors g

- Page 202 and 203:

How to generalize one-dimensional e

- Page 204 and 205:

needed to support the object in fig

- Page 206 and 207:

The easiest method is the one demon

- Page 208 and 209:

Incorrect solution #4:(same notatio

- Page 210 and 211:

The magnitude of the acceleration i

- Page 212 and 213:

dropped out like a trap door, showi

- Page 214 and 215:

af / Breaking trail, by WalterE. Bo

- Page 216 and 217:

know how to integrate with respect

- Page 218 and 219:

ProblemsThe symbols √ , , etc. ar

- Page 220 and 221:

Problem 16.Problem 19.resistance.)1

- Page 222 and 223:

of gravity on Mars.(a) Find the tim

- Page 224 and 225:

partner force. (a) A swimmer speeds

- Page 226 and 227:

Problem 45the 0.4-gram masses would

- Page 228 and 229:

53 If you walk 35 km at an angle 25

- Page 230 and 231:

(b) Interpret this equation in the

- Page 232 and 233:

Problem 71.232 Chapter 3 Conservati

- Page 234 and 235:

77 A car accelerates from rest. At

- Page 236 and 237:

Problem 81.81 Complete example 71 o

- Page 238 and 239:

ExercisesExercise 3A: Force and Mot

- Page 240 and 241:

Exercise 3C: Worksheet on Resonance

- Page 242 and 243:

Exercise 3D: Vectors and MotionEach

- Page 244 and 245:

244 Chapter 3 Conservation of Momen

- Page 246 and 247:

An overhead view of apiece of putty

- Page 248 and 249:

inward toward the hinge will have n

- Page 250 and 251:

special case, we can choose to visu

- Page 252 and 253:

j / Two asteroids collide.k / Every

- Page 254 and 255:

Note that although the factors of 2

- Page 256 and 257:

Relationship between force and torq

- Page 258 and 259:

is straight down, which is perpendi

- Page 260 and 261:

⊲ All three objects in the figure

- Page 262 and 263:

aa / Example 10.to either side of e

- Page 264 and 265:

momentum tells us that L = mrv sin

- Page 266 and 267:

In the absence of any torque, a rig

- Page 268 and 269:

Radial acceleration at the surface

- Page 270 and 271:

The parallel axis theorem example 1

- Page 272 and 273:

differential. The result isarea ===

- Page 274 and 275:

of inertia as if the object was smo

- Page 276 and 277:

h / Moments of inertia of somegeome

- Page 278 and 279:

4.3 Angular Momentum In Three Dimen

- Page 280 and 281:

14 deg, and it points along an axis

- Page 282 and 283:

manner like this, then the definiti

- Page 284 and 285:

k / Example 27.torque to the left w

- Page 286 and 287:

We can also generalize the plane-ro

- Page 288 and 289:

Problem 1.Problem 6.Problem 8.Probl

- Page 290 and 291:

14 (a) The bar of mass m is attache

- Page 292 and 293:

Problem 22.22 The sun turns on its

- Page 294 and 295:

35 The nucleus 168 Er (erbium-168)

- Page 296 and 297:

ExercisesExercise 4A: TorqueEquipme

- Page 298 and 299:

pesky set of constraints on heat en

- Page 300 and 301:

mit more air into the cavity behind

- Page 302 and 303:

Pressure of lava underneath a volca

- Page 304 and 305:

h / A simplified version of anideal

- Page 306 and 307:

for us to construct a simple connec

- Page 308 and 309:

For the first time we have an inter

- Page 310 and 311:

a / 1. The temperature differencebe

- Page 312 and 313:

Carnot engines operating between a

- Page 314 and 315:

from A to B, he lets it by, but whe

- Page 316 and 317:

B When we run the Carnot engine in

- Page 318 and 319:

f / A phase space for a singleatom

- Page 320 and 321:

time, the energy sharing is very un

- Page 322 and 323:

will the the one that maximizes the

- Page 324 and 325:

If the gas is monoatomic, then we k

- Page 326 and 327:

5.4.4 The arrow of time, or “this

- Page 328 and 329:

5.4.6 Summary of the laws of thermo

- Page 330 and 331:

may be in the form of microscopic d

- Page 332 and 333:

significant amount of heat to flow

- Page 334 and 335:

while the smaller area under the bo

- Page 336 and 337:

7 (a) Determine the ratio between t

- Page 338 and 339:

338 Chapter 5 Thermodynamics

- Page 340 and 341:

end of this book, we’ll even see

- Page 342 and 343:

c / As the wave pattern passes the

- Page 344 and 345:

the wave move ahead faster and get

- Page 346 and 347:

k / Hitting a key on a pianocauses

- Page 348 and 349:

Our final result for the speed of t

- Page 350 and 351:

care, because the delay is the same

- Page 352 and 353:

An easy way to visualize this is in

- Page 354 and 355:

can be constructed as a superpositi

- Page 356 and 357:

⊲ Looking up the speed of light i

- Page 358 and 359:

scientists, to speak of the Big Ban

- Page 360 and 361:

6.2 Bounded WavesSpeech is what sep

- Page 362 and 363:

d / An uninverted reflection. There

- Page 364 and 365:

our intuitive expectation of strong

- Page 366 and 367:

valid solutions. In the following s

- Page 368 and 369:

j / In the mirror image, theareas o

- Page 370 and 371:

m / A pulse bounces backand forth.i

- Page 372 and 373:

q / Graphs of loudness versusfreque

- Page 374 and 375:

s / Standing waves on a rope. (PSSC

- Page 376 and 377: “cavity” and “neck” parts o

- Page 378 and 379: Problem 5.Problem 8.5 The figure sh

- Page 380 and 381: Problem 16.16 A Fabry-Perot interfe

- Page 382 and 383: c / Newton’s laws do not distingu

- Page 384 and 385: f / The correspondence principlereq

- Page 386 and 387: d / A Galilean version of therelati

- Page 388 and 389: g / Three types of transformations

- Page 390 and 391: system, velocities are always unitl

- Page 392 and 393: p / Apparatus used for the testof r

- Page 394 and 395: sumption, the assumption that it ma

- Page 396 and 397: at rest relative to the water. But

- Page 398 and 399: 7.2.4 No action at a distanceThe Ne

- Page 400 and 401: so that Alice can complete her moti

- Page 402 and 403: time into different regions accordi

- Page 404 and 405: position relative to the sun at exa

- Page 406 and 407: 7.2.7 ⋆ Four-vectors and the inne

- Page 408 and 409: would depend on the relative veloci

- Page 410 and 411: 7.3 DynamicsSo far we have said not

- Page 412 and 413: In this frame, as expected, the sma

- Page 414 and 415: But this whole argument was based o

- Page 416 and 417: meters per second, so converting to

- Page 418 and 419: Expressing γ as ( 1 − v 2 /c 2)

- Page 420 and 421: 7.3.4 ⋆ ProofsThis optional secti

- Page 422 and 423: these lines. For example, a car sit

- Page 424 and 425: An Einstein’s ring. Thedistant ob

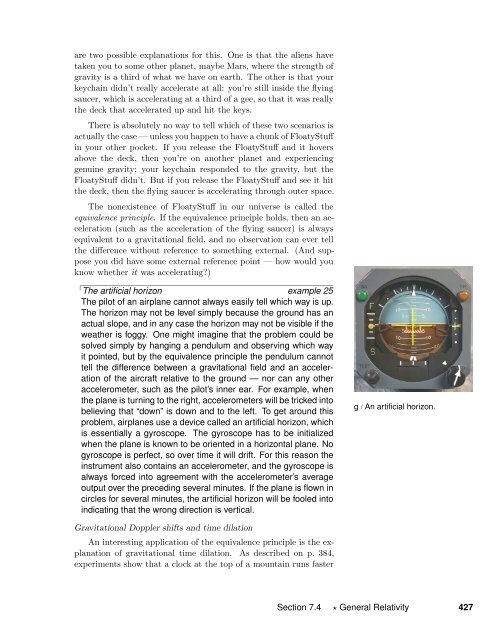

- Page 428 and 429: h / 1. A ray of light is emittedupw

- Page 430 and 431: object that that isn’t influenced

- Page 432 and 433: it impossible for any observer to b

- Page 434 and 435: a variant on the Penrose singularit

- Page 436 and 437: in it. Instead, it is currently spe

- Page 438 and 439: 2 Astronauts in three different spa

- Page 440 and 441: (d) Simplify your answer to part c

- Page 442 and 443: Problem 25b. Redrawn fromVan Baak,

- Page 444 and 445: ExercisesExercise 7A: The Michelson

- Page 446 and 447: Exercise 7B: Sports in Slowlightlan

- Page 448 and 449: 448 Chapter 7 Relativity

- Page 450 and 451: Exercise 7D: Misconceptions about R

- Page 452 and 453: 452 Chapter 7 Relativity

- Page 454 and 455: sun, moon, stars, and planets were

- Page 456 and 457: Two types of chargeWe can easily co

- Page 458 and 459: the other acquires an equal amount

- Page 460 and 461: to get the beam up to speed in the

- Page 462 and 463: telling us that we know about matte

- Page 464 and 465: the muddle. The row-and-column sche

- Page 466 and 467: the force of air friction canceled

- Page 468 and 469: ectly evaluate the implications of

- Page 470 and 471: that they were indeed electrically

- Page 472 and 473: C Thomson found that the m/q of an

- Page 474 and 475: the object with a net positive char

- Page 476 and 477:

thickness of material the radioacti

- Page 478 and 479:

It was already known that although

- Page 480 and 481:

particle. It turned out that it was

- Page 482 and 483:

For example they could easily strip

- Page 484 and 485:

cording to Mosely, the atomic numbe

- Page 486 and 487:

that fly off to see what was inside

- Page 488 and 489:

solution was found by measuring the

- Page 490 and 491:

o / A nuclear power plant at Catten

- Page 492 and 493:

neutrons. In a nuclear fission bomb

- Page 494 and 495:

We can now list all four of the kno

- Page 496 and 497:

1. Our sun’s source of energy is

- Page 498 and 499:

a / The known nuclei, represented o

- Page 500 and 501:

killed, because the DNA becomes una

- Page 502 and 503:

e / Wild Przewalski’s horsesprosp

- Page 504 and 505:

Problem 1. Top: A realisticpicture

- Page 506 and 507:

12 The subatomic particles called m

- Page 508 and 509:

ExercisesExercise 8A: Nuclear decay

- Page 510 and 511:

saxophone, every technological tool

- Page 512 and 513:

Example 1Ions moving across a cell

- Page 514 and 515:

ut the original meaning was to trav

- Page 516 and 517:

Force depends only on position. Sin

- Page 518 and 519:

Here are a few questions and answer

- Page 520 and 521:

flow through it.For many substances

- Page 522 and 523:

superconductivity in metals that wo

- Page 524 and 525:

j / Example 9. In 1 and 2,charges t

- Page 526 and 527:

look like the usual resistor. The f

- Page 528 and 529:

9.1.5 Current-conducting properties

- Page 530 and 531:

attery acid becomes depleted of hyd

- Page 532 and 533:

9.2 Parallel and Series CircuitsIn

- Page 534 and 535:

to each resistance, resulting inI t

- Page 536 and 537:

where “...” means that the sum

- Page 538 and 539:

the two resistors in figure h/3.We

- Page 540 and 541:

Choice of high voltage for power li

- Page 542 and 543:

A complicated circuit example 20⊲

- Page 544 and 545:

Problem 2.ProblemsThe symbols √ ,

- Page 546 and 547:

Problem 16.only count that as one u

- Page 548 and 549:

knob turned all the way clockwise,

- Page 550 and 551:

A printed circuit board, likethe ki

- Page 552 and 553:

ExercisesExercise 9A: Voltage and C

- Page 554 and 555:

Exercise 9C: Reasoning About Circui

- Page 556 and 557:

556 Chapter 9 Circuits

- Page 558 and 559:

a / A bar magnet’s atoms are(part

- Page 560 and 561:

defined. The ship’s captain can m

- Page 562 and 563:

Reduction in gravity on Io due to J

- Page 564 and 565:

j / Example 3.self-check AFind an e

- Page 566 and 567:

a dipole moment — they are define

- Page 568 and 569:

10.2.1 One dimensionVoltage is elec

- Page 570 and 571:

The interpretation is that if you b

- Page 572 and 573:

Figure c shows some examples of way

- Page 574 and 575:

For large values of d, this express

- Page 576 and 577:

where Q is the total charge of the

- Page 578 and 579:

g / Example 12: variation of the fi

- Page 580 and 581:

corners to the disk and transform i

- Page 582 and 583:

10.4 Energy In Fieldsa / Two opposi

- Page 584 and 585:

self-check DWe can think of the qua

- Page 586 and 587:

of the inward field contributed by

- Page 588 and 589:

space, 2 while charge doesn’t, we

- Page 590 and 591:

a / The symbol for a capacitor.b /

- Page 592 and 593:

ounding each capacitor will be half

- Page 594 and 595:

in time:x ↔ qv ↔ Iself-check GH

- Page 596 and 597:

due to its own momentum. It perform

- Page 598 and 599:

or|V | =∣ LdIdt ∣ ,which in man

- Page 600 and 601:

the inductor resists such a sudden

- Page 602 and 603:

Example 26.Death by solenoid; spark

- Page 604 and 605:

ordering.( 1 √2+√ i ) 2 = √ 1

- Page 606 and 607:

x / The complex number e iφlies on

- Page 608 and 609:

Figure aa shows a useful way to vis

- Page 610 and 611:

Inductors tend to be big, heavy, ex

- Page 612 and 613:

The reason for using the trig ident

- Page 614 and 615:

a purely inductive or capacitive lo

- Page 616 and 617:

Resonance with damping example 33

- Page 618 and 619:

orE outward, on side 1 A + E outwar

- Page 620 and 621:

|E| = kq totalr 2 ,where r is the r

- Page 622 and 623:

y considering its point charges ind

- Page 624 and 625:

Discussion Questionsg / Discussion

- Page 626 and 627:

with charge, change the Coulomb con

- Page 628 and 629:

The symmetry between the two sides

- Page 630 and 631:

where dv is the volume of the cube.

- Page 632 and 633:

The three terms in the divergence a

- Page 634 and 635:

ProblemsThe symbols √ , , etc. ar

- Page 636 and 637:

Problem 19.Problem 20.proton, for e

- Page 638 and 639:

the lightning strike.(b) Based on y

- Page 640 and 641:

units.(b) Verify that RC has units

- Page 642 and 643:

lating freely (without any driving

- Page 644 and 645:

ExercisesExercise 10A: Field Vector

- Page 646 and 647:

5. Now hook up the two solenoids in

- Page 648 and 649:

A large current is createdby shorti

- Page 650 and 651:

time I used it implicitly was in fi

- Page 652 and 653:

f / A standard dipole madefrom a sq

- Page 654 and 655:

and substituting q = λh and v = m/

- Page 656 and 657:

o / Magnetic forces cause abeam of

- Page 658 and 659:

electric field, a magnetic one, can

- Page 660 and 661:

u / In this scene from SwanLake, th

- Page 662 and 663:

so the total field in the z directi

- Page 664 and 665:

For the y component, we havee / A s

- Page 666 and 667:

We can pin down the result even mor

- Page 668 and 669:

i / The field of a dipole.where r i

- Page 670 and 671:

circulates around the y axis, so at

- Page 672 and 673:

to be, not where it is now. Coulomb

- Page 674 and 675:

We have found one specific example

- Page 676 and 677:

to a flagpole, we can cancel out a

- Page 678 and 679:

11.4 Ampère’s Law In Differentia

- Page 680 and 681:

y evaluating the field at the midpo

- Page 682 and 683:

i.e.,F = axˆx + byˆx + cˆx + dx

- Page 684 and 685:

k / A summary of the derivative, gr

- Page 686 and 687:

c / Detail from Ascending andDescen

- Page 688 and 689:

the magnet. Are these atomic curren

- Page 690 and 691:

field in her region of space has be

- Page 692 and 693:

A changing magnetic flux makes a cu

- Page 694 and 695:

nearly zero. By Faraday’s law, th

- Page 696 and 697:

c / An Ampèrian surface superimpos

- Page 698 and 699:

and Maxwell’s equations becomeΦ

- Page 700 and 701:

k / Red and blue light travelat the

- Page 702 and 703:

second, the zero-point is located a

- Page 704 and 705:

is the magnitude of the momentum ve

- Page 706 and 707:

Discussion question A.Discussion qu

- Page 708 and 709:

only penetrates to a very small dep

- Page 710 and 711:

elationship D = ɛE would actually

- Page 712 and 713:

esulting in cancellation.The opposi

- Page 714 and 715:

a low permeability, while the other

- Page 716 and 717:

n / A fluxgate compass.is externall

- Page 718 and 719:

6 Two parallel wires of length L ca

- Page 720 and 721:

an instant at the upper right, but

- Page 722 and 723:

Problem 25.20 Four long wires are a

- Page 724 and 725:

Problem 35.Problem 37.32 Verify Amp

- Page 726 and 727:

Problem 42.beam of light usually co

- Page 728 and 729:

(c) Discuss the relationship betwee

- Page 730 and 731:

(f) Use conservation of energy to r

- Page 732 and 733:

5. Now position yourself with your

- Page 734 and 735:

12.1.1 The nature of lightThe cause

- Page 736 and 737:

An image of Jupiter andits moon Io

- Page 738 and 739:

d / Two self-portraits of theauthor

- Page 740 and 741:

ultimate truth about light, but the

- Page 742 and 743:

• There is a tendency to conceptu

- Page 744 and 745:

self-check AEach of these diagrams

- Page 746 and 747:

m / Discussion question B.Discussio

- Page 748 and 749:

12.2 Images by ReflectionInfants ar

- Page 750 and 751:

Discussion QuestionA The figure sho

- Page 752 and 753:

down magnification is AB/DE. A repe

- Page 754 and 755:

i / A Newtonian telescopebeing used

- Page 756 and 757:

B Locate the images formed by two p

- Page 758 and 759:

12.3 Images, QuantitativelyIt sound

- Page 760 and 761:

⊲ The object and image angles are

- Page 762 and 763:

12.3.2 Other cases with curved mirr

- Page 764 and 765:

signs also have to be memorized for

- Page 766 and 767:

h / A diverging mirror in the shape

- Page 768 and 769:

j / Spherical mirrors are thecheape

- Page 770 and 771:

general type of eye that we share w

- Page 772 and 773:

shown on this graph and then attemp

- Page 774 and 775:

the mechanical model would predict

- Page 776 and 777:

that your calculator will flash an

- Page 778 and 779:

D Classify the examples shown in fi

- Page 780 and 781:

12.4.6 ⋆ Microscopic description

- Page 782 and 783:

12.5 Wave OpticsElectron microscope

- Page 784 and 785:

of a crystal? Sound waves are used

- Page 786 and 787:

j / Thomas Youngk / Double-slit dif

- Page 788 and 789:

object that diffracts it, so the tr

- Page 790 and 791:

Although the equation λ/d = sin θ

- Page 792 and 793:

things we’ve learned about diffra

- Page 794 and 795:

apidly changing distances; on reuni

- Page 796 and 797:

6 The figure on the next page shows

- Page 798 and 799:

14 Here’s a game my kids like to

- Page 800 and 801:

27 Suppose a converging lens is con

- Page 802 and 803:

same depth, but not quite. [Check:

- Page 804 and 805:

Problem 42.42 Panel 1 of the figure

- Page 806 and 807:

46 The figure below shows two diffr

- Page 808 and 809:

53 The beam of a laser passes throu

- Page 810 and 811:

Problem 59.the ancient problem of i

- Page 812 and 813:

3. Now imagine the following new si

- Page 814 and 815:

Exercise 12B: Object and Image Dist

- Page 816 and 817:

Exercise 12D: Double-Source Interfe

- Page 818 and 819:

Exercise 12E: Single-slit diffracti

- Page 820 and 821:

Exercise 12F: Diffraction of LightE

- Page 822 and 823:

energy, instead of being spread out

- Page 824 and 825:

correlated. If they have been playi

- Page 826 and 827:

small.The statement that the rule f

- Page 828 and 829:

But the y axis can no longer be a u

- Page 830 and 831:

for a long time once it gets there,

- Page 832 and 833:

j / Calibration of the 14 C dating

- Page 834 and 835:

given by(probability of a ≤ x ≤

- Page 836 and 837:

k / In recent decades, a huge hole

- Page 838 and 839:

A wave is partially absorbed.c / A

- Page 840 and 841:

f / The hamster in her hamsterball

- Page 842 and 843:

How would you extract h from the gr

- Page 844 and 845:

F Does E = hf imply that a photon c

- Page 846 and 847:

of approaching this issue.)j / Bull

- Page 848 and 849:

We assume v is small enough so that

- Page 850 and 851:

the probability distribution will b

- Page 852 and 853:

trons that we have already used for

- Page 854 and 855:

equations of general validity are t

- Page 856 and 857:

wave carries high probability and w

- Page 858 and 859:

An infinite sine wave can only tell

- Page 860 and 861:

momentum implies a definite kinetic

- Page 862 and 863:

of snapshots would amount to a desc

- Page 864 and 865:

close are the electrons to the limi

- Page 866 and 867:

dimensional particle in a box, and

- Page 868 and 869:

Applying this to conservation of en

- Page 870 and 871:

the probability of making it throug

- Page 872 and 873:

Three dimensionsFor simplicity, we

- Page 874 and 875:

1. Oscillations can go backand fort

- Page 876 and 877:

C The figure shows a skateboarder t

- Page 878 and 879:

a / Eight wavelengths fit aroundthi

- Page 880 and 881:

As shown by these examples, the unc

- Page 882 and 883:

e / The three states of the hydroge

- Page 884 and 885:

f / The energy levels of a particle

- Page 886 and 887:

∂r/∂x = x/r comes in handy. Com

- Page 888 and 889:

50% of its time in each atom. It’

- Page 890 and 891:

tus to the z axis) and more memorab

- Page 892 and 893:

ut why does that have anything to d

- Page 894 and 895:

the data are only inaccurate due to

- Page 896 and 897:

14 The photoelectric effect can occ

- Page 898 and 899:

Problem 25.(b) Sketch a graph showi

- Page 900 and 901:

conservation of energy and momentum

- Page 902 and 903:

Problem 43.43 On pp. 884-885 of sub

- Page 904 and 905:

ExercisesExercise 13A: Quantum Vers

- Page 906 and 907:

⊲ First we convert the equation i

- Page 908 and 909:

Programming With PythonThe purpose

- Page 910 and 911:

Appendix 2: MiscellanyUnphysical

- Page 912 and 913:

18 bestt = t19 c1 = bestc120 c2 = b

- Page 914 and 915:

p i + ∑ iThe spin theoremTheorem:

- Page 916 and 917:

Appendix 3: Photo CreditsExcept as

- Page 918 and 919:

Appendix 4: Hints and SolutionsHint

- Page 920 and 921:

Hints for Chapter 6Page 377, proble

- Page 922 and 923:

Answers to Self-Checks for Chapter

- Page 924 and 925:

Page 301: (1) Not valid. The equati

- Page 926 and 927:

Page 584:N −1 m −2 C 2 V 2 m

- Page 928 and 929:

the dashed ray.Page 748: You should

- Page 930 and 931:

direction it was initially going (i

- Page 932 and 933:

Page 52, problem 38: The cone of mi

- Page 934 and 935:

Page 224, problem 37: (a) Spring co

- Page 936 and 937:

object, we have static friction, wh

- Page 938 and 939:

Page 549, problem 29:(a) Conservati

- Page 940 and 941:

Page 798, problem 19: (a) The objec

- Page 942 and 943:

.0.8 Notation and unitsquantity uni

- Page 944 and 945:

surfaces. For comparison, a typical

- Page 946 and 947:

elations:a = ∆v∆tx = 1 2 at2 +

- Page 948 and 949:

we are moving along with the projec

- Page 950 and 951:

the number of oscillations required

- Page 952 and 953:

In general, the cross product of ve

- Page 954 and 955:

Sound waves consist of increases an

- Page 956 and 957:

signs for charge is that with this

- Page 958 and 959:

know that there is a delay in time

- Page 960 and 961:

is related byΦ = 4πkq into the ch

- Page 962 and 963:

to use sophisticated models such as

- Page 964 and 965:

Chapter 13, Quantum Physics, page 8

- Page 966 and 967:

oth position and momentum, the Heis

- Page 968 and 969:

Schrödinger’s, 864cathode rays,

- Page 970 and 971:

unstable, 87equipartition theorem,

- Page 972 and 973:

Joule, James, 73paddlewheel experim

- Page 974 and 975:

Einstein’s early theory, 838energ

- Page 976 and 977:

Nikola, 178tesla (unit), 652thermal