- Page 2:

© World Meteorological Organizatio

- Page 8 and 9:

The second lead authors meeting was

- Page 12 and 13:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONatmospheric

- Page 14 and 15:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONThe impact

- Page 16 and 17:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONEquations 1

- Page 18 and 19:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONThere is a

- Page 20 and 21:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONFigure 8 -

- Page 22 and 23:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONLow-income

- Page 24 and 25:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION1.5 SCIENTI

- Page 26 and 27:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONFigure 12 -

- Page 28 and 29:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONthese aeros

- Page 30 and 31:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONFigure 16:

- Page 32 and 33:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONFigure 18 -

- Page 34 and 35:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONReferencesA

- Page 36 and 37:

CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONLeibensperg

- Page 38 and 39:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICACoordinating auth

- Page 40 and 41:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAFigure 3 displays

- Page 42 and 43:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAabout 2,000 mm pe

- Page 44 and 45:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAFigure 5 - NO2 me

- Page 46 and 47:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAIn West-African c

- Page 48 and 49:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAratios in Bamako

- Page 50 and 51:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAAs shown in Figur

- Page 52 and 53:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAof the city of Jo

- Page 54 and 55:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAlow smoke coal wa

- Page 56 and 57:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAcompleted, their

- Page 58 and 59:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAepidemiological d

- Page 60 and 61:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAPopulationGrowthR

- Page 62 and 63:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAcycle with levels

- Page 64 and 65:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAcomparable to tho

- Page 66 and 67:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICAFavez, O., Sciare

- Page 68 and 69:

CHAPTER 2 - AFRICASeagrave, J., McD

- Page 70 and 71:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAThe bottom-up and t

- Page 72 and 73:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 2 - (a) CO e

- Page 74 and 75:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAand Kim Oanh, 2002]

- Page 76 and 77:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 4 - Annual a

- Page 78 and 79:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAmaintenance program

- Page 80 and 81:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAnearly half of the

- Page 82 and 83:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIARelationships of th

- Page 84 and 85:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 12 - Graphic

- Page 86 and 87:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAAnother significant

- Page 88 and 89:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAand international),

- Page 90 and 91:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 17 - (a) Var

- Page 92 and 93:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAEmissions inventory

- Page 94 and 95:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAAir Quality Index r

- Page 96 and 97:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIA• Strict restrict

- Page 98 and 99:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAis due the ban of l

- Page 100 and 101:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAAvailability of air

- Page 102 and 103:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 26 - Box plo

- Page 104 and 105:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAResearch projects o

- Page 106 and 107:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAmonitoring stations

- Page 108 and 109:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIApreliminary stage.

- Page 110 and 111:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIATable 8 - National

- Page 112 and 113:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAControl strategiesA

- Page 114 and 115:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAMetro Manila Air Qu

- Page 116 and 117:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAmoves inland and O

- Page 118 and 119:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAHong Kong and Macau

- Page 120 and 121:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 39 - A 52-ye

- Page 122 and 123:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAClimatic change iss

- Page 124 and 125:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAEmission sources of

- Page 126 and 127:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAIn the case of PM 1

- Page 128 and 129:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAdue to yellow sand

- Page 130 and 131:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAEmission inventorie

- Page 132 and 133:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAatmosphere, which i

- Page 134 and 135:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAEmissions of NO X f

- Page 136 and 137:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAFigure 58 - Annuall

- Page 138 and 139:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAThe predominance of

- Page 140 and 141:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAthe negative health

- Page 142 and 143:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAAsrari, E., Ghole,

- Page 144 and 145:

CHAPTER 3 - ASIAGuo H, Fine AJ, So

- Page 146 and 147: CHAPTER 3 - ASIALi L., Chen C.H., H

- Page 148 and 149: CHAPTER 3 - ASIAPollution Control D

- Page 150 and 151: CHAPTER 3 - ASIAYu JZ, Tung JWT, Wu

- Page 152 and 153: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAand human

- Page 154 and 155: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICA4.1.2 Emis

- Page 156 and 157: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICATable 4 -

- Page 158 and 159: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAemissions

- Page 160 and 161: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAthird moun

- Page 162 and 163: 4.3 BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINACHAPTER

- Page 164 and 165: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAless than

- Page 166 and 167: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICApart of Sa

- Page 168 and 169: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAThe Nation

- Page 170 and 171: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICA4.7 SÃO P

- Page 172 and 173: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAhydrocarbo

- Page 174 and 175: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICAthat such

- Page 176 and 177: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICACorvalán,

- Page 178 and 179: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICALongo, K.

- Page 180 and 181: CHAPTER 4 - SOUTH AMERICARomero Lan

- Page 182 and 183: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICACoordinati

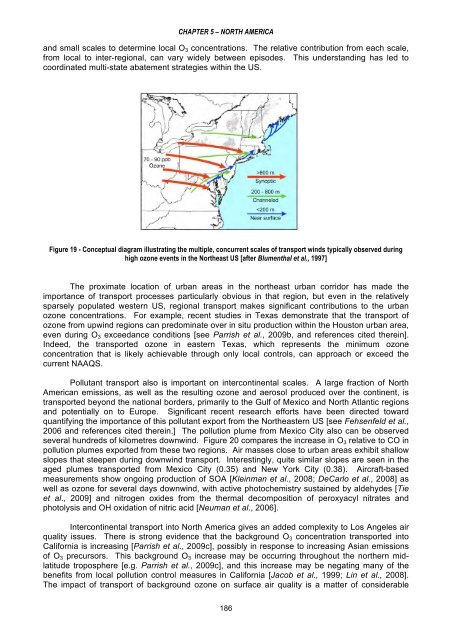

- Page 184 and 185: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICAstories fo

- Page 186 and 187: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICAthat impro

- Page 188 and 189: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICA5.2 THE US

- Page 190 and 191: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICAcontributi

- Page 192 and 193: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICAseason fro

- Page 194 and 195: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICAtoluene, a

- Page 198 and 199: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICABlumenthal

- Page 200 and 201: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICALei, W., Z

- Page 202 and 203: CHAPTER 5 - NORTH AMERICAVelasco, E

- Page 204 and 205: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 1 shows a

- Page 206 and 207: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPE6.1.3 Pollution l

- Page 208 and 209: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 4 - [Carsl

- Page 210 and 211: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 7 - Greate

- Page 212 and 213: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 9 - Partit

- Page 214 and 215: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFrom a regulatory

- Page 216 and 217: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEB) Particulate ma

- Page 218 and 219: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPE• During the wi

- Page 220 and 221: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 17 - Total

- Page 222 and 223: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEair quality in th

- Page 224 and 225: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEfaculty of MSU, I

- Page 226 and 227: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPE2007; Andersson e

- Page 228 and 229: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPETable 3b - Past a

- Page 230 and 231: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEexpectancy in NRW

- Page 232 and 233: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEtime range of sev

- Page 234 and 235: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 25 - Inhab

- Page 236 and 237: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEPiemonte (Turin):

- Page 238 and 239: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEFigure 31 - Numbe

- Page 240 and 241: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEAs for the develo

- Page 242 and 243: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEsub-tropical fron

- Page 244 and 245: CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEpollutants around

- Page 246 and 247:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEaddition to local

- Page 248 and 249:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEprecipitation sam

- Page 250 and 251:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEstrict legislatio

- Page 252 and 253:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPECaserini, S., Fra

- Page 254 and 255:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPEHodzic A., C. H.,

- Page 256 and 257:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPELondon, T. f. Cle

- Page 258 and 259:

CHAPTER 6 - EUROPETebaldi, G., Angi

- Page 260 and 261:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 262 and 263:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 264 and 265:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 266 and 267:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 268 and 269:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 270 and 271:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 272 and 273:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 274 and 275:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 276 and 277:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 278 and 279:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 280 and 281:

7.9 PRIDE-PRDCHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW O

- Page 282 and 283:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 284 and 285:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 286 and 287:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 288 and 289:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 290 and 291:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 292 and 293:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 294 and 295:

CHAPTER 7 - OVERVIEW OF INTERNATION

- Page 296 and 297:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKa

- Page 298 and 299:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKi

- Page 300 and 301:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKa

- Page 302 and 303:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKT

- Page 304 and 305:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKs

- Page 306 and 307:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKr

- Page 308 and 309:

CHAPTER 8 - KEY ISSUES AND OUTLOOKM

- Page 310 and 311:

LIST OF RECENT GLOBAL ATMOSPHERE WA

- Page 312 and 313:

141. Report of the LAP/COST/WMO Int

- Page 314:

185. Guidelines for the Measurement