Bulletin de liaison et d'information - Institut kurde de Paris

Bulletin de liaison et d'information - Institut kurde de Paris

Bulletin de liaison et d'information - Institut kurde de Paris

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

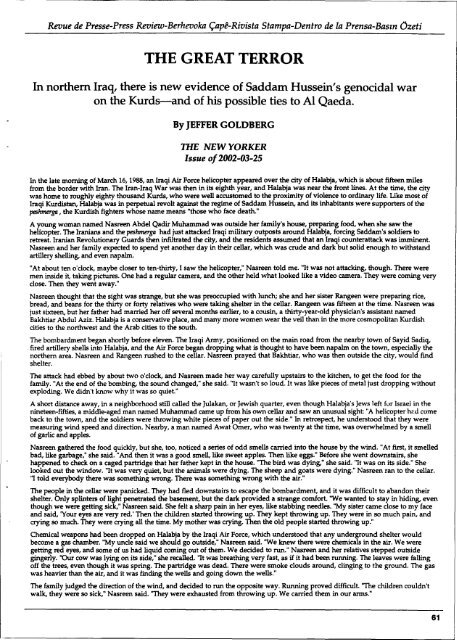

Revue <strong>de</strong> Presse-Press Review-Berhevoka Çapê-Rivista Stampa-Dentro <strong>de</strong> la Prensa-Basm Oz<strong>et</strong>i<br />

THE GREAT TERROR<br />

In northern Iraq, there is new evi<strong>de</strong>nce of Saddam Hussein's genocidal war<br />

on the Kurds-and of his possible ties to Al Qaeda.<br />

By JEFFER GOLDBERG<br />

mE NEW YORKER<br />

Issue of 2002-03-25<br />

Inthe late morning of March 16,1988, an Iraqi Air Force helicopter appeared over the city of Halabja, which is about fifteen miles<br />

from the bor<strong>de</strong>r with Iran. The Iran-Iraq War was then in its eighth year, and Halabja was near the front lines. At the time, the city<br />

was home to roughly eighty thousand Kurds, who were well accustomed to the proximity of violence to ordinary life. Like most of<br />

Iraqi Kurdistan, Halabja was in perp<strong>et</strong>ual revolt against the regime of Saddam Hussein, and its inhabitants were supporters of the<br />

peshmerga, the Kurdish fighters whose name means "those who face <strong>de</strong>ath."<br />

A young woman named Nasreen Ab<strong>de</strong>l Qadir Muhammad was outsi<strong>de</strong> her family's house, preparing food, when she saw the<br />

helicopter. The Iranians and the peshmerga had just attacked Iraqi military outposts around Halabja, forcing Saddam's soldiers to<br />

r<strong>et</strong>reat. Iranian Revolutionary Guards then infiltrated the city, and the resi<strong>de</strong>nts assumed that an Iraqi counterattack was imminent.<br />

Nasreen and her family expected to spend y<strong>et</strong> another day in their cellar, which was cru<strong>de</strong> and dark but solid enough to withstand<br />

artillery shelling, and even napalm.<br />

"At about ten o'clock, maybe closer to ten-thirty, I saw the helicopter," Nasreen told me. "It was not attacking, though. There were<br />

men insi<strong>de</strong> it, taking pictures. One had a regular camera, and the other held what looked like a vi<strong>de</strong>o camera. They were coming very<br />

close. Then they went away."<br />

Nasreen thought that the sight was strange, but she was preoccupied with lunch; she and her sister Rangeen were preparing rice,<br />

bread, and beans for the thirty or forty relatives who were taking shelter in the cellar. Rangeen was fifteen at the time. Nasreen was<br />

just sixteen, but her father had married her off several months earlier, to a cousin, a thirty-year-old physician's assistant named<br />

Bakhtiar Abdul Aziz. Halabja is a conservative place, and many more women wear the veil than in the more cosmopolitan Kurdish<br />

cities to the northwest and the Arab cities to the south.<br />

The bombardment began shortly before eleven. The Iraqi Army, positioned on the main road from the nearby town of Sayid Sadiq,<br />

. fired artillery shells into Halabja, and the Air Force began dropping what is thought to have been napalm on the town, especially the<br />

northern area. Nasreen and Rangeen rushed to the cellar. Nasreen prayed that Bakhtiar, who was then outsi<strong>de</strong> the city, would find<br />

shelter.<br />

The attack had ebbed by about two o'clock, and Nasreen ma<strong>de</strong> her way carefully upstairs to the kitchen, to g<strong>et</strong> the food for the<br />

family. "At the end of the bombing, the sound changed," she said. "It wasn't so loud. It was like pieces of m<strong>et</strong>al just dropping without<br />

exploding. We didn't know why it was so qui<strong>et</strong>."<br />

A short distance away, in a neighborhood still called the Julakan, or Jewish quarter, even though Halabja's Jews left fur Israel in the<br />

nin<strong>et</strong>een-fifties, a middle-aged man named Muhammad came up from his own cellar and saw an unusual sight "A helicopter hï:d come<br />

back to the town, and the soldiers were throwing white pieces of paper out the si<strong>de</strong>." In r<strong>et</strong>rospect, he un<strong>de</strong>rstood that they were<br />

measuring wind speed and direction. Nearby, a man named Awat Omer, who was twenty at the time, was overwhelmed by a smell<br />

of garlic and apples.<br />

Nasreen gathered the food quickly, but she, too, noticed a series of odd smells carried into the house by the wind. "At first, it smelled<br />

bad, like garbage," she said. "And then it was a good smell, like swe<strong>et</strong> apples. Then like eggs." Before she went downstairs, she<br />

happened to cheek on a caged partridge that her father kept in the house. "The bird was dying," she said. "It was on its si<strong>de</strong>." She<br />

looked out the window. "It was very qui<strong>et</strong>, but the animais were dying. The sheep and goats were dying." Nasreen ran to the cellar.<br />

"I told everybody there was som<strong>et</strong>hing wrong. There was som<strong>et</strong>hing wrong with the air."<br />

The people in the cellar were panicked. They had fled downstairs to escape the bombardment, and it was difficult to abandon their<br />

shelter. Only splinters of light pen<strong>et</strong>rated the basement, but the dark provi<strong>de</strong>d a strange comfort. 'We wanted to stay in hiding, even<br />

though we were g<strong>et</strong>ting sick," Nasreen said. She felt a sharp pain in her eyes, like stabbing needles. "My sister came close to my face<br />

and said, 'Your eyes are very red.' Then the children started throwing up. They kept throwing up. They were in so much pain, and<br />

crying so much. They were crying all the time. My mother was crying. Then the old people started throwing up."<br />

Chemical weapons had been dropped on Halabja by the Iraqi Air Force, which un<strong>de</strong>rstood that any un<strong>de</strong>rground shelter would<br />

become a gas chamber. "My uncle said we should go outsi<strong>de</strong>," Nasreen said. "We knew there were chemicals in the air. We were<br />

g<strong>et</strong>ting red eyes, and some of us had liquid coming out of them. We <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to run." Nasreen and her relatives stepped outsi<strong>de</strong><br />

gingerly. "Our cow was lying on its si<strong>de</strong>," she recalled. 'lt was breathing very fast, as if it had been running. The leaves were falling<br />

off the trees, even though it was spring. The partridge was <strong>de</strong>ad. There were smoke clouds around, clinging to the ground. The gas<br />

was heavier than the air, and it was finding the wells and going down the wells."<br />

The family judged the direction of the wind, and <strong>de</strong>ci<strong>de</strong>d to run the opposite way. Running proved difficult. "The children couldn't<br />

walk, they were so sick," Nasreen said. "They were exhausted from throwing up. We carried them in our arms."<br />

61