American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

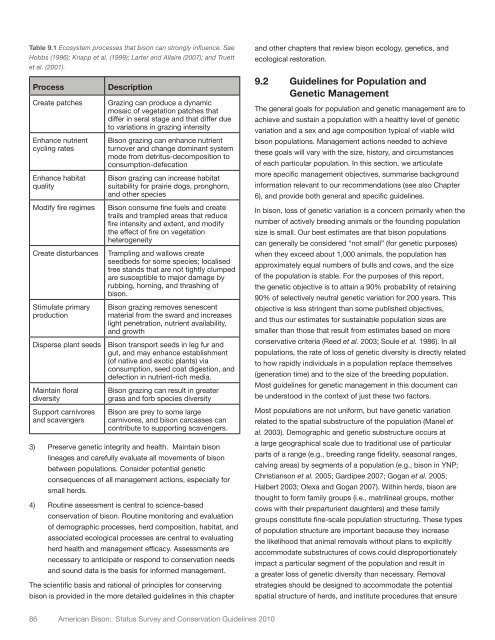

Table 9.1 Ecosystem processes that bison can strongly influence. See<br />

Hobbs (1996); Knapp et al. (1999); Larter and Allaire (2007); and Truett<br />

et al. (2001).<br />

Process Description<br />

Create patches Grazing can produce a dynamic<br />

mosaic of vegetation patches that<br />

differ in seral stage and that differ due<br />

to variations in grazing intensity<br />

Enhance nutrient<br />

cycling rates<br />

Enhance habitat<br />

quality<br />

3) Preserve genetic integrity and health. Maintain bison<br />

lineages and carefully evaluate all movements of bison<br />

between populations. Consider potential genetic<br />

consequences of all management actions, especially for<br />

small herds.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> grazing can enhance nutrient<br />

turnover and change dominant system<br />

mode from detritus-decomposition to<br />

consumption-defecation<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> grazing can increase habitat<br />

suitability for prairie dogs, pronghorn,<br />

and other species<br />

Modify fire regimes <strong>Bison</strong> consume fine fuels and create<br />

trails and trampled areas that reduce<br />

fire intensity and extent, and modify<br />

the effect of fire on vegetation<br />

heterogeneity<br />

Create disturbances Trampling and wallows create<br />

seedbeds for some species; localised<br />

tree stands that are not tightly clumped<br />

are susceptible to major damage by<br />

rubbing, horning, and thrashing of<br />

bison.<br />

Stimulate primary<br />

production<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> grazing removes senescent<br />

material from the sward and increases<br />

light penetration, nutrient availability,<br />

and growth<br />

Disperse plant seeds <strong>Bison</strong> transport seeds in leg fur and<br />

gut, and may enhance establishment<br />

(of native and exotic plants) via<br />

consumption, seed coat digestion, and<br />

defection in nutrient-rich media.<br />

Maintain floral<br />

diversity<br />

Support carnivores<br />

and scavengers<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> grazing can result in greater<br />

grass and forb species diversity<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> are prey to some large<br />

carnivores, and bison carcasses can<br />

contribute to supporting scavengers.<br />

4) Routine assessment is central to science-based<br />

conservation of bison. Routine monitoring and evaluation<br />

of demographic processes, herd composition, habitat, and<br />

associated ecological processes are central to evaluating<br />

herd health and management efficacy. Assessments are<br />

necessary to anticipate or respond to conservation needs<br />

and sound data is the basis for informed management.<br />

The scientific basis and rational of principles for conserving<br />

bison is provided in the more detailed guidelines in this chapter<br />

86 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010<br />

and other chapters that review bison ecology, genetics, and<br />

ecological restoration.<br />

9.2 Guidelines for Population and<br />

Genetic Management<br />

The general goals for population and genetic management are to<br />

achieve and sustain a population with a healthy level of genetic<br />

variation and a sex and age composition typical of viable wild<br />

bison populations. Management actions needed to achieve<br />

these goals will vary with the size, history, and circumstances<br />

of each particular population. In this section, we articulate<br />

more specific management objectives, summarise background<br />

information relevant to our recommendations (see also Chapter<br />

6), and provide both general and specific guidelines.<br />

In bison, loss of genetic variation is a concern primarily when the<br />

number of actively breeding animals or the founding population<br />

size is small. Our best estimates are that bison populations<br />

can generally be considered “not small” (for genetic purposes)<br />

when they exceed about 1,000 animals, the population has<br />

approximately equal numbers of bulls and cows, and the size<br />

of the population is stable. For the purposes of this report,<br />

the genetic objective is to attain a 90% probability of retaining<br />

90% of selectively neutral genetic variation for 200 years. This<br />

objective is less stringent than some published objectives,<br />

and thus our estimates for sustainable population sizes are<br />

smaller than those that result from estimates based on more<br />

conservative criteria (Reed et al. 2003; Soule et al. 1986). In all<br />

populations, the rate of loss of genetic diversity is directly related<br />

to how rapidly individuals in a population replace themselves<br />

(generation time) and to the size of the breeding population.<br />

Most guidelines for genetic management in this document can<br />

be understood in the context of just these two factors.<br />

Most populations are not uniform, but have genetic variation<br />

related to the spatial substructure of the population (Manel et<br />

al. 2003). Demographic and genetic substructure occurs at<br />

a large geographical scale due to traditional use of particular<br />

parts of a range (e.g., breeding range fidelity, seasonal ranges,<br />

calving areas) by segments of a population (e.g., bison in YNP;<br />

Christianson et al. 2005; Gardipee 2007; Gogan et al. 2005;<br />

Halbert 2003; Olexa and Gogan 2007). Within herds, bison are<br />

thought to form family groups (i.e., matrilineal groups, mother<br />

cows with their preparturient daughters) and these family<br />

groups constitute fine-scale population structuring. These types<br />

of population structure are important because they increase<br />

the likelihood that animal removals without plans to explicitly<br />

accommodate substructures of cows could disproportionately<br />

impact a particular segment of the population and result in<br />

a greater loss of genetic diversity than necessary. Removal<br />

strategies should be designed to accommodate the potential<br />

spatial structure of herds, and institute procedures that ensure