American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Chapter 6 General Biology, Ecology and<br />

Demographics<br />

6.1 General Biology<br />

An understanding of the ecology and biology of bison is<br />

fundamental to their successful management, conservation,<br />

and restoration. <strong>Bison</strong> have the broadest original range of<br />

any indigenous ungulate species in North America, reflecting<br />

physiological, morphological, and behavioural adaptations that<br />

permit them to thrive in diverse ecosystems that provide their<br />

diet of grasses and sedges. Successful population management,<br />

conservation of genetic diversity and natural selection, modelling<br />

and predicting population level responses to human activities,<br />

and managing population structure all depend on understanding<br />

the biological characteristics and ecological roles of bison. The<br />

purpose of this chapter is to summarise what is currently known<br />

about the biology of bison; for an earlier comprehensive review,<br />

see Reynolds et al. (2003).<br />

6.1.1 Physiology<br />

6.1.1.1 Metabolism<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> exhibit seasonal variation in energy metabolism.<br />

Christopherson et al. (1979) and Rutley and Hudson (2000)<br />

observed that metabolisable energy intake and requirements of<br />

yearling male bison were markedly lower in winter than summer.<br />

This was attributed to a reduction in activity and acclimation.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> are better adapted to temperature extremes than most<br />

breeds of cattle. They expend less energy under extreme<br />

cold than do cattle because of the greater insulating<br />

capacity of their pelage (Peters and Slen 1964).<br />

Cold tolerance of hybrids between bison and cattle<br />

is intermediate between the two species (Smoliak<br />

and Peters 1955). Tolerance of bison to heat has not<br />

been studied, but the original continental range of<br />

the species included the dry, hot desert grasslands of<br />

northern Mexico, where a small population of plains<br />

bison still exists today (List et al. 2007).<br />

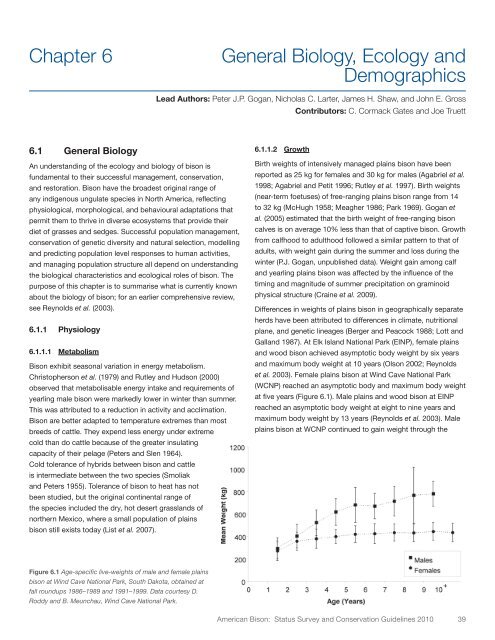

Figure 6.1 Age-specific live-weights of male and female plains<br />

bison at Wind Cave National Park, South Dakota, obtained at<br />

fall roundups 1986–1989 and 1991–1999. Data courtesy D.<br />

Roddy and B. Meunchau, Wind Cave National Park.<br />

Lead Authors: Peter J.P. Gogan, Nicholas C. Larter, James H. Shaw, and John E. Gross<br />

6.1.1.2 Growth<br />

Contributors: C. Cormack Gates and Joe Truett<br />

Birth weights of intensively managed plains bison have been<br />

reported as 25 kg for females and 30 kg for males (Agabriel et al.<br />

1998; Agabriel and Petit 1996; Rutley et al. 1997). Birth weights<br />

(near-term foetuses) of free-ranging plains bison range from 14<br />

to 32 kg (McHugh 1958; Meagher 1986; Park 1969). Gogan et<br />

al. (2005) estimated that the birth weight of free-ranging bison<br />

calves is on average 10% less than that of captive bison. Growth<br />

from calfhood to adulthood followed a similar pattern to that of<br />

adults, with weight gain during the summer and loss during the<br />

winter (P.J. Gogan, unpublished data). Weight gain among calf<br />

and yearling plains bison was affected by the influence of the<br />

timing and magnitude of summer precipitation on graminoid<br />

physical structure (Craine et al. 2009).<br />

Differences in weights of plains bison in geographically separate<br />

herds have been attributed to differences in climate, nutritional<br />

plane, and genetic lineages (Berger and Peacock 1988; Lott and<br />

Galland 1987). At Elk Island National Park (EINP), female plains<br />

and wood bison achieved asymptotic body weight by six years<br />

and maximum body weight at 10 years (Olson 2002; Reynolds<br />

et al. 2003). Female plains bison at Wind Cave National Park<br />

(WCNP) reached an asymptotic body and maximum body weight<br />

at five years (Figure 6.1). Male plains and wood bison at EINP<br />

reached an asymptotic body weight at eight to nine years and<br />

maximum body weight by 13 years (Reynolds et al. 2003). Male<br />

plains bison at WCNP continued to gain weight through the<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 39