American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

historically dependent on a combination of bison wallows and<br />

prairie dog colonies for nesting sites. These areas were also<br />

utilised by ferruginous hawks (Buteo regalis) and long-billed<br />

curlew (Numenius americanus) (Knopf 1996). Brown-headed<br />

cowbirds (Molothrus ater), also called buffalo birds, occurred<br />

in association with bison throughout central North <strong>American</strong><br />

grasslands prior to the introduction of livestock (Friedman 1929).<br />

Cowbirds feed on insects moving in response to foraging bison<br />

(Goguen and Mathews 1999; Webster 2005). Grasshopper<br />

species richness, composition, and abundance are strongly<br />

influenced by interactions between bison grazing and fire<br />

frequency (Joern 2005; Jonas and Joern 2007).<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> facilitated dispersal of the seeds of many plant taxa as a<br />

result of the seeds becoming temporarily attached to the bison’s<br />

hair (Berthoud 1892; Rosas et al. 2008) or via passage through<br />

the digestive tract (Gokbulak 2002). Peak passage rate for seeds<br />

was 2 days following ingestion (Gokbulak 2002).<br />

Horning damage to trees along grassland borders is effective<br />

in slowing invasion of trees into shrub and grassland plant<br />

communities or in extending the existing grassland into the<br />

forest margin. <strong>Bison</strong> within YNP rubbed and horned lodgepole<br />

pine (Pinus contorta) trees around the periphery of open<br />

grasslands to the extent that some were completely girdled<br />

(Meagher 1973). Similarly horning by wood bison in the MBS<br />

has resulted in completely girdled white spruce stands on<br />

the periphery of mesic sedge meadows and willow savannas<br />

(N.C. Larter, personal observation). Several authors (Campbell<br />

et al. 1994; Coppedge and Shaw 1997; Edwards 1978) have<br />

suggested that bison, in combination with other factors such as<br />

fire and drought, significantly limited the historic distribution of<br />

woody vegetation on the Great Plains.<br />

A decomposing bison carcass initially kills the underlying plants,<br />

but subsequently provides a pulse of nutrients, creating a<br />

disturbed area of limited competition with abundant resources<br />

that enhances plant community heterogeneity (Towne 2000).<br />

Carrion from dead bison is an important food resource for both<br />

grizzly and black bears (Ursus americana) as well as scavenging<br />

birds such as bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), ravens<br />

(Corvus corax), and black-billed magpies (Pica pica).<br />

6.2.1.2 Contemporary habitat use, nutrition, and foraging<br />

The bison is a ruminant with a four-chambered stomach and<br />

associations of symbiotic microorganisms that assist digestion<br />

of fibrous forage. On lower quality forage, such as grasses<br />

and sedges, bison achieve greater digestive efficiencies than<br />

domestic cattle, but on high quality forages such as alfalfa, the<br />

digestive efficiency of bison and cattle converge (Reynolds et al.<br />

2003). Contemporary studies of plains bison habitat selection<br />

in North <strong>American</strong> grasslands are limited to confined herds<br />

artificially maintained at varying densities (Table 6.1)—some of<br />

which may differ markedly from pristine conditions (Fahnestock<br />

and Detling 2002).<br />

Herbivores, including bison, respond to gradients in forage<br />

quality and quantity. Hornaday (1889) described a highly<br />

nomadic foraging strategy, where plains bison seemed to<br />

wander somewhat aimlessly until they located a patch with<br />

favourable grazing. A bison herd would then remain and graze<br />

until the need for water motivated further movement. This<br />

account contrasts with more recent studies of bison foraging,<br />

which have found that plains bison actively select more<br />

nutritious forages, and forage in a highly efficient manner that<br />

satisfies their nutritional needs and compliments diet selection<br />

by sympatric herbivores (Coppock et al. 1983a; 1983b; Hudson<br />

and Frank 1987; Singer and Norland 1994; Wallace et al. 1995).<br />

Spatial variation in forage quality and quantity results from<br />

natural gradients in soil moisture, soil nutrients, fire, and other<br />

disturbance, as well as from the impacts of foraging by bison.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> exploit variations in forage quality and quantity at all<br />

scales; from selecting small patches of highly nutritious forages<br />

on prairie dog towns, to undertaking long-distance migration in<br />

response to seasonal snowfall or drought.<br />

The following review of bison habitat interactions is based upon<br />

North <strong>American</strong> ecoregions identified by Ricketts et al. (1999)<br />

and aggregated by Sanderson et al. (2008).<br />

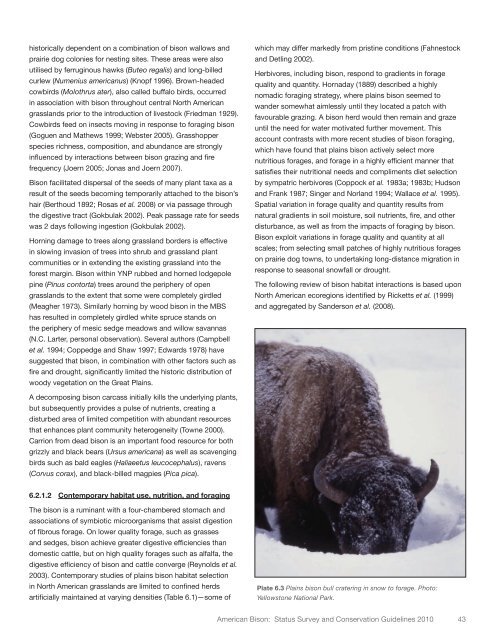

Plate 6.3 Plains bison bull cratering in snow to forage. Photo:<br />

Yellowstone National Park.<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 43