American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

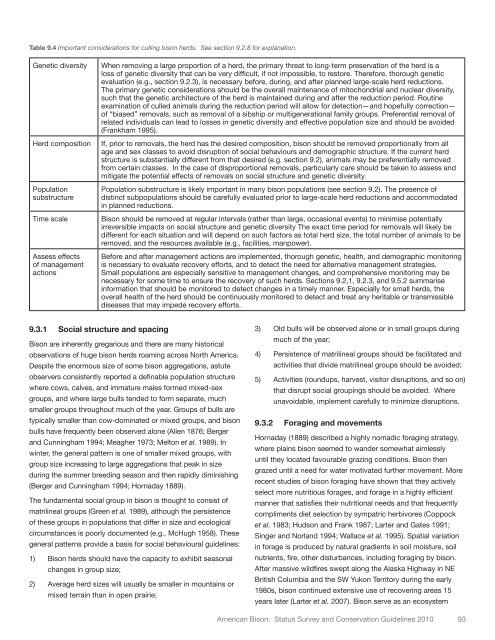

Table 9.4 Important considerations for culling bison herds. See section 9.2.8 for explanation.<br />

Genetic diversity When removing a large proportion of a herd, the primary threat to long-term preservation of the herd is a<br />

loss of genetic diversity that can be very difficult, if not impossible, to restore. Therefore, thorough genetic<br />

evaluation (e.g., section 9.2.3), is necessary before, during, and after planned large-scale herd reductions.<br />

The primary genetic considerations should be the overall maintenance of mitochondrial and nuclear diversity,<br />

such that the genetic architecture of the herd is maintained during and after the reduction period. Routine<br />

examination of culled animals during the reduction period will allow for detection—and hopefully correction—<br />

of “biased” removals, such as removal of a sibship or multigenerational family groups. Preferential removal of<br />

related individuals can lead to losses in genetic diversity and effective population size and should be avoided<br />

(Frankham 1995).<br />

Herd composition If, prior to removals, the herd has the desired composition, bison should be removed proportionally from all<br />

age and sex classes to avoid disruption of social behaviours and demographic structure. If the current herd<br />

structure is substantially different from that desired (e.g. section 9.2), animals may be preferentially removed<br />

from certain classes. In the case of disproportional removals, particularly care should be taken to assess and<br />

mitigate the potential effects of removals on social structure and genetic diversity.<br />

Population<br />

substructure<br />

9.3.1 Social structure and spacing<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> are inherently gregarious and there are many historical<br />

observations of huge bison herds roaming across North America.<br />

Despite the enormous size of some bison aggregations, astute<br />

observers consistently reported a definable population structure<br />

where cows, calves, and immature males formed mixed-sex<br />

groups, and where large bulls tended to form separate, much<br />

smaller groups throughout much of the year. Groups of bulls are<br />

typically smaller than cow-dominated or mixed groups, and bison<br />

bulls have frequently been observed alone (Allen 1876; Berger<br />

and Cunningham 1994; Meagher 1973; Melton et al. 1989). In<br />

winter, the general pattern is one of smaller mixed groups, with<br />

group size increasing to large aggregations that peak in size<br />

during the summer breeding season and then rapidly diminishing<br />

(Berger and Cunningham 1994; Hornaday 1889).<br />

The fundamental social group in bison is thought to consist of<br />

matrilineal groups (Green et al. 1989), although the persistence<br />

of these groups in populations that differ in size and ecological<br />

circumstances is poorly documented (e.g., McHugh 1958). These<br />

general patterns provide a basis for social behavioural guidelines:<br />

1) <strong>Bison</strong> herds should have the capacity to exhibit seasonal<br />

changes in group size;<br />

Population substructure is likely important in many bison populations (see section 9.2). The presence of<br />

distinct subpopulations should be carefully evaluated prior to large-scale herd reductions and accommodated<br />

in planned reductions.<br />

Time scale <strong>Bison</strong> should be removed at regular intervals (rather than large, occasional events) to minimise potentially<br />

irreversible impacts on social structure and genetic diversity The exact time period for removals will likely be<br />

different for each situation and will depend on such factors as total herd size, the total number of animals to be<br />

removed, and the resources available (e.g., facilities, manpower).<br />

Assess effects<br />

of management<br />

actions<br />

Before and after management actions are implemented, thorough genetic, health, and demographic monitoring<br />

is necessary to evaluate recovery efforts, and to detect the need for alternative management strategies.<br />

Small populations are especially sensitive to management changes, and comprehensive monitoring may be<br />

necessary for some time to ensure the recovery of such herds. Sections 9.2,1, 9.2.3, and 9.5.2 summarise<br />

information that should be monitored to detect changes in a timely manner. Especially for small herds, the<br />

overall health of the herd should be continuously monitored to detect and treat any heritable or transmissible<br />

diseases that may impede recovery efforts.<br />

2) Average herd sizes will usually be smaller in mountains or<br />

mixed terrain than in open prairie;<br />

3) Old bulls will be observed alone or in small groups during<br />

much of the year;<br />

4) Persistence of matrilineal groups should be facilitated and<br />

activities that divide matrilineal groups should be avoided;<br />

5) Activities (roundups, harvest, visitor disruptions, and so on)<br />

that disrupt social groupings should be avoided. Where<br />

unavoidable, implement carefully to minimize disruptions.<br />

9.3.2 Foraging and movements<br />

Hornaday (1889) described a highly nomadic foraging strategy,<br />

where plains bison seemed to wander somewhat aimlessly<br />

until they located favourable grazing conditions. <strong>Bison</strong> then<br />

grazed until a need for water motivated further movement. More<br />

recent studies of bison foraging have shown that they actively<br />

select more nutritious forages, and forage in a highly efficient<br />

manner that satisfies their nutritional needs and that frequently<br />

compliments diet selection by sympatric herbivores (Coppock<br />

et al. 1983; Hudson and Frank 1987; Larter and Gates 1991;<br />

Singer and Norland 1994; Wallace et al. 1995). Spatial variation<br />

in forage is produced by natural gradients in soil moisture, soil<br />

nutrients, fire, other disturbances, including foraging by bison.<br />

After massive wildfires swept along the Alaska Highway in NE<br />

British Columbia and the SW Yukon Territory during the early<br />

1980s, bison continued extensive use of recovering areas 15<br />

years later (Larter et al. 2007). <strong>Bison</strong> serve as an ecosystem<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 93