American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

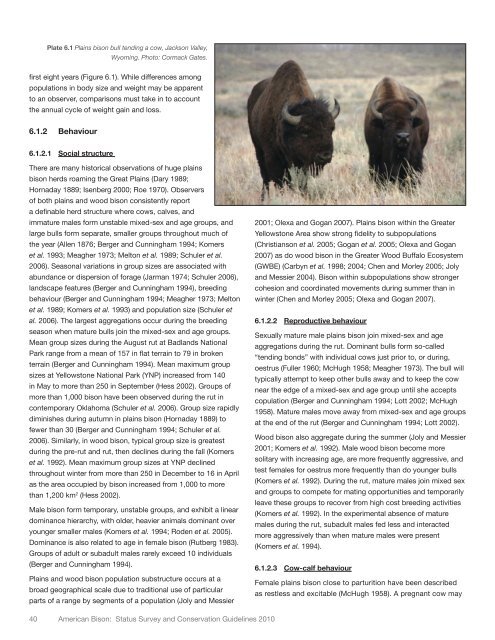

Plate 6.1 Plains bison bull tending a cow, Jackson Valley,<br />

first eight years (Figure 6.1). While differences among<br />

populations in body size and weight may be apparent<br />

to an observer, comparisons must take in to account<br />

the annual cycle of weight gain and loss.<br />

6.1.2 Behaviour<br />

6.1.2.1 Social structure<br />

There are many historical observations of huge plains<br />

bison herds roaming the Great Plains (Dary 1989;<br />

Hornaday 1889; Isenberg 2000; Roe 1970). Observers<br />

of both plains and wood bison consistently report<br />

a definable herd structure where cows, calves, and<br />

immature males form unstable mixed-sex and age groups, and<br />

large bulls form separate, smaller groups throughout much of<br />

the year (Allen 1876; Berger and Cunningham 1994; Komers<br />

et al. 1993; Meagher 1973; Melton et al. 1989; Schuler et al.<br />

2006). Seasonal variations in group sizes are associated with<br />

abundance or dispersion of forage (Jarman 1974; Schuler 2006),<br />

landscape features (Berger and Cunningham 1994), breeding<br />

behaviour (Berger and Cunningham 1994; Meagher 1973; Melton<br />

et al. 1989; Komers et al. 1993) and population size (Schuler et<br />

al. 2006). The largest aggregations occur during the breeding<br />

season when mature bulls join the mixed-sex and age groups.<br />

Mean group sizes during the August rut at Badlands National<br />

Park range from a mean of 157 in flat terrain to 79 in broken<br />

terrain (Berger and Cunningham 1994). Mean maximum group<br />

sizes at Yellowstone National Park (YNP) increased from 140<br />

in May to more than 250 in September (Hess 2002). Groups of<br />

more than 1,000 bison have been observed during the rut in<br />

contemporary Oklahoma (Schuler et al. 2006). Group size rapidly<br />

diminishes during autumn in plains bison (Hornaday 1889) to<br />

fewer than 30 (Berger and Cunningham 1994; Schuler et al.<br />

2006). Similarly, in wood bison, typical group size is greatest<br />

during the pre-rut and rut, then declines during the fall (Komers<br />

et al. 1992). Mean maximum group sizes at YNP declined<br />

throughout winter from more than 250 in December to 16 in April<br />

as the area occupied by bison increased from 1,000 to more<br />

than 1,200 km 2 (Hess 2002).<br />

Male bison form temporary, unstable groups, and exhibit a linear<br />

dominance hierarchy, with older, heavier animals dominant over<br />

younger smaller males (Komers et al. 1994; Roden et al. 2005).<br />

Dominance is also related to age in female bison (Rutberg 1983).<br />

Groups of adult or subadult males rarely exceed 10 individuals<br />

(Berger and Cunningham 1994).<br />

Wyoming. Photo: Cormack Gates.<br />

Plains and wood bison population substructure occurs at a<br />

broad geographical scale due to traditional use of particular<br />

parts of a range by segments of a population (Joly and Messier<br />

40 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010<br />

2001; Olexa and Gogan 2007). Plains bison within the Greater<br />

Yellowstone Area show strong fidelity to subpopulations<br />

(Christianson et al. 2005; Gogan et al. 2005; Olexa and Gogan<br />

2007) as do wood bison in the Greater Wood <strong>Buffalo</strong> Ecosystem<br />

(GWBE) (Carbyn et al. 1998; 2004; Chen and Morley 2005; Joly<br />

and Messier 2004). <strong>Bison</strong> within subpopulations show stronger<br />

cohesion and coordinated movements during summer than in<br />

winter (Chen and Morley 2005; Olexa and Gogan 2007).<br />

6.1.2.2 Reproductive behaviour<br />

Sexually mature male plains bison join mixed-sex and age<br />

aggregations during the rut. Dominant bulls form so-called<br />

“tending bonds” with individual cows just prior to, or during,<br />

oestrus (Fuller 1960; McHugh 1958; Meagher 1973). The bull will<br />

typically attempt to keep other bulls away and to keep the cow<br />

near the edge of a mixed-sex and age group until she accepts<br />

copulation (Berger and Cunningham 1994; Lott 2002; McHugh<br />

1958). Mature males move away from mixed-sex and age groups<br />

at the end of the rut (Berger and Cunningham 1994; Lott 2002).<br />

Wood bison also aggregate during the summer (Joly and Messier<br />

2001; Komers et al. 1992). Male wood bison become more<br />

solitary with increasing age, are more frequently aggressive, and<br />

test females for oestrus more frequently than do younger bulls<br />

(Komers et al. 1992). During the rut, mature males join mixed sex<br />

and groups to compete for mating opportunities and temporarily<br />

leave these groups to recover from high cost breeding activities<br />

(Komers et al. 1992). In the experimental absence of mature<br />

males during the rut, subadult males fed less and interacted<br />

more aggressively than when mature males were present<br />

(Komers et al. 1994).<br />

6.1.2.3 Cow-calf behaviour<br />

Female plains bison close to parturition have been described<br />

as restless and excitable (McHugh 1958). A pregnant cow may