American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

leave the herd prior to calving or give birth within the herd<br />

(McHugh 1958). Similarly, for wood bison in the Mackenzie<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> Sanctuary (MBS), females have been observed calving<br />

in the midst of herds or in extreme isolation in the forest away<br />

from any other animals (N.C. Larter, personal observation).<br />

Birthing normally occurs while the female is lying down. The<br />

mother typically consumes portions of the afterbirth as she<br />

frees the calf from the membranes (Lott 2002; McHugh 1958).<br />

The female licks amniotic fluid from the calf’s fur (Lott 2002).<br />

Suckling begins shortly after birth and may last as long as<br />

10 minutes (McHugh 1958); although there was a report of a<br />

wood bison mother attacking the newborn calf during suckling<br />

(Carbyn and Trottier 1987). The close contact between a<br />

cow and calf begins to decline after the calf’s first week of<br />

life (Green 1992). A calf is typically weaned by seven to eight<br />

months of age, although nursing may extend beyond 12<br />

months (Green et al. 1993). The longest associations among<br />

bison are between cows and their female offspring; while male<br />

offspring may remain with the cow through a second summer,<br />

female offspring may remain with the cow through a third<br />

summer (Green et al. 1989; Shaw and Carter 1988).<br />

The cow may use quick charges or steady advances to defend<br />

a calf against threats (Garretson 1938; Hornaday 1889; McHugh<br />

1958). An isolated plains bison cow vigorously defended her<br />

calf from a grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), even though the bear was<br />

ultimately successful in killing the calf (Varley and Gunther 2002).<br />

Similarly, an isolated cow vigorously defended the calf from<br />

wolves (Canis lupus) (C. Freese, personal communication).<br />

Cows and other members of mixed-sex and age groups may<br />

cooperatively protect calves from predators. In response to the<br />

approach of a grizzly bear, a mixed-sex and age group of adult<br />

plains bison responded by facing the bear in a compact group,<br />

with the calves running behind the adults (Gunther 1991). Wolves<br />

preferentially attempt to prey upon wood bison mixed-sex and<br />

age groups that include calves (Carbyn and Trottier 1987). During<br />

wolf attacks, calves moved close to the cow, or<br />

to other bison, or to the centre of the bison group<br />

(Carbyn and Trottier 1987; 1988), although this<br />

defensive response may break down when bison<br />

groups move through forested areas that may<br />

impede the movements of the calves (Carbyn and<br />

Trottier 1988).<br />

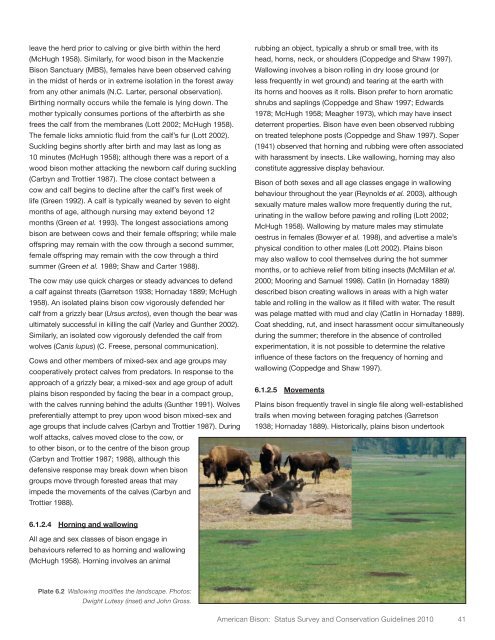

6.1.2.4 Horning and wallowing<br />

All age and sex classes of bison engage in<br />

behaviours referred to as horning and wallowing<br />

(McHugh 1958). Horning involves an animal<br />

Plate 6.2 Wallowing modifies the landscape. Photos:<br />

Dwight Lutesy (inset) and John Gross.<br />

rubbing an object, typically a shrub or small tree, with its<br />

head, horns, neck, or shoulders (Coppedge and Shaw 1997).<br />

Wallowing involves a bison rolling in dry loose ground (or<br />

less frequently in wet ground) and tearing at the earth with<br />

its horns and hooves as it rolls. <strong>Bison</strong> prefer to horn aromatic<br />

shrubs and saplings (Coppedge and Shaw 1997; Edwards<br />

1978; McHugh 1958; Meagher 1973), which may have insect<br />

deterrent properties. <strong>Bison</strong> have even been observed rubbing<br />

on treated telephone posts (Coppedge and Shaw 1997). Soper<br />

(1941) observed that horning and rubbing were often associated<br />

with harassment by insects. Like wallowing, horning may also<br />

constitute aggressive display behaviour.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> of both sexes and all age classes engage in wallowing<br />

behaviour throughout the year (Reynolds et al. 2003), although<br />

sexually mature males wallow more frequently during the rut,<br />

urinating in the wallow before pawing and rolling (Lott 2002;<br />

McHugh 1958). Wallowing by mature males may stimulate<br />

oestrus in females (Bowyer et al. 1998), and advertise a male’s<br />

physical condition to other males (Lott 2002). Plains bison<br />

may also wallow to cool themselves during the hot summer<br />

months, or to achieve relief from biting insects (McMillan et al.<br />

2000; Mooring and Samuel 1998). Catlin (in Hornaday 1889)<br />

described bison creating wallows in areas with a high water<br />

table and rolling in the wallow as it filled with water. The result<br />

was pelage matted with mud and clay (Catlin in Hornaday 1889).<br />

Coat shedding, rut, and insect harassment occur simultaneously<br />

during the summer; therefore in the absence of controlled<br />

experimentation, it is not possible to determine the relative<br />

influence of these factors on the frequency of horning and<br />

wallowing (Coppedge and Shaw 1997).<br />

6.1.2.5 Movements<br />

Plains bison frequently travel in single file along well-established<br />

trails when moving between foraging patches (Garretson<br />

1938; Hornaday 1889). Historically, plains bison undertook<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 41