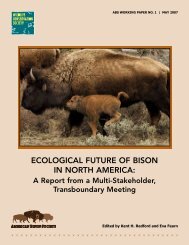

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

demonstrate that <strong>Bison</strong> and Bos were genetically similar, given<br />

molecular methods existing at the time (Beintema et al. 1986;<br />

Bhambhani and Kuspira 1969; Dayhoff 1972; Kleinschmidt<br />

and Sgouros 1987; Stormont et al. 1961; Wilson et al. 1985).<br />

Additionally, the percent divergences among mitochondrial<br />

DNA (MtDNA) sequences of <strong>Bison</strong> bison, Bos grunniens, and<br />

Bos taurus were comparable to those calculated among other<br />

sets of congeneric species assessed until 1989 (Miyamoto et<br />

al. 1989). Reproductive information also supports the inference<br />

of a close phylogenetic relationship between Bos and <strong>Bison</strong>;<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> and some members of Bos can hybridise under forced<br />

mating to produce partially fertile female offspring (Miyamoto et<br />

al. 1989; Van Gelder 1977; Wall et al. 1992; Ward 2000). Species<br />

divergence and reproductive incompatibility are evident with<br />

the low fertility of first generation (F1) bison x cattle offspring<br />

(Boyd 1908; Steklenev and Yasinetskaya 1982) and the difficulty<br />

producing viable male offspring (Boyd 1908; Goodnight 1914;<br />

Steklenev and Yasinetskaya 1982; Steklenev et al. 1986).<br />

Behavioural incompatibility is also evident. Although mating<br />

of bison and cattle can readily be achieved in a controlled<br />

environment, they preferentially associate and mate with<br />

individuals of their own species under open range conditions<br />

(Boyd 1908; 1914; Goodnight 1914; Jones 1907). Differences<br />

in digestive physiology and diet selection between cattle and<br />

<strong>American</strong> bison (reviewed by Reynolds et al. 2003) and European<br />

bison (Gębczyńska and Krasińska 1972) provide further evidence<br />

of the antiquity of divergence between cattle and bison. Based<br />

on palaeontological evidence, Loftus et al. (1994) concluded<br />

that the genera Bos and <strong>Bison</strong> shared a common ancestor<br />

1,000,000–1,400,000 years ago.<br />

In North America, sympatry between bison and cattle is an<br />

artefact of the recent history of colonisation by Europeans and<br />

their livestock. However, in prehistoric Europe, the wisent (<strong>Bison</strong><br />

bonasus) and aurochs (Bos taurus primigeneus), the progenitor<br />

of modern cattle, were sympatric yet evolutionarily divergent<br />

units. The divergence in behaviour, morphology, physiology, and<br />

ecology observed between bison and cattle is consistent with<br />

the theory that ecological specialisation in sympatric species<br />

occupying similar trophic niches provides a mechanism for<br />

reducing competition in the absence of geographic isolation<br />

(Bush 1975; Rice and Hostert 1993).<br />

The assignment of an animal to a genus in traditional naming<br />

schemes can be subjective, and changing generic names can<br />

create confusion and contravene the goal of taxonomy, which is<br />

to stabilise nomenclature (Winston 1999). However, we caution<br />

that maintaining a stable nomenclature should not occur at<br />

the expense of misrepresenting relationships. A change of<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> to Bos may reflect inferred evolutionary relationships and<br />

genetic similarities between <strong>Bison</strong> and Bos species. It could<br />

also potentially provide continuity and stability to the scientific<br />

reference for bison, which currently has two species names in use<br />

(B. bonasus and B. bison). However, and in contrast, based on<br />

divergence on a cytochrome b gene sequence analysis, Prusak et<br />

al. (2004) concluded that although <strong>American</strong> and European bison<br />

are closely related, they should be treated as separate species of<br />

the genus <strong>Bison</strong>, rather than subspecies of a bison species. There<br />

is also the potential that changing the genus from <strong>Bison</strong> to Bos<br />

would complicate management of European (three subspecies)<br />

and <strong>American</strong> bison (two subspecies) at the subspecies level<br />

and disrupt an established history of public policy and scientific<br />

community identification with the genus <strong>Bison</strong>.<br />

Further research and debate by taxonomists and the bison<br />

conservation community is required to reconcile molecular,<br />

behavioural and morphological evidence before a change<br />

in nomenclature could be supported by the <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong><br />

Specialist Group (ABSG). In consideration of the uncertainties<br />

explained above, and in keeping with the naming conventions<br />

for mammals used for the 1996 Red List and the 2008 Red List<br />

(Wilson and Reeder 1993; Wilson and Reeder 2005), the ABSG<br />

adheres to the genus <strong>Bison</strong> with two species, European bison<br />

(B. bonasus) and <strong>American</strong> bison (B. bison), in this document.<br />

3.3 Subspecies<br />

A controversial aspect of <strong>American</strong> bison taxonomy is the<br />

legitimacy of the subspecies designations for plains bison (B.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> bison) and wood bison (B. bison athabascae). The two<br />

subspecies were first distinguished in 1897, when Rhoads<br />

formally recognised the wood bison subspecies as B. bison<br />

athabascae based on descriptions of the animal (Rhoads<br />

1897). Although the two variants differ in skeletal and external<br />

morphology and pelage characteristics (Table 3.1), some<br />

scientists have argued that these differences alone do not<br />

adequately substantiate subspecies designation (Geist 1991).<br />

The issue is complicated by the human-induced hybridisation<br />

between plains bison and wood bison that was encouraged<br />

in Wood <strong>Buffalo</strong> National Park (WBNP) during the 1920s.<br />

Furthermore, the concept of what constitutes a subspecies<br />

continues to evolve.<br />

The assignment of subspecific status varies with the organism,<br />

the taxonomist, and which of the various definitions of<br />

subspecies is applied. Mayr and Ashlock (1991:430) define a<br />

subspecies as “an aggregate of local populations of a species<br />

inhabiting a geographic subdivision of the range of the species<br />

and differing taxonomically from other populations of the<br />

species.” Avise and Ball (1990:59-60) adapted their definition<br />

from the Biological Species Concept, which defines species as<br />

groups of organisms that are reproductively isolated from other<br />

groups (Mayr and Ashlock 1991): “Subspecies are groups of<br />

actually or potentially interbreeding populations phylogenetically<br />

distinguishable from, but reproductively compatible with, other<br />

such groups.”<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 15