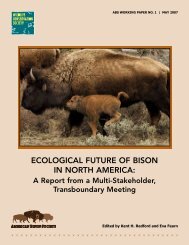

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

attempted (Nishi et al. 2002b), but failed. In 2006, after 10 years<br />

of isolation and rigorous disease testing, BTB-infected bison<br />

were detected in the herd.<br />

Several constituencies rejected the FEARO (1990) panel’s<br />

recommendation to depopulate WBNP herds. The Northern<br />

<strong>Buffalo</strong> Management Board (NBMB) was formed to develop<br />

a feasible eradication plan (Chisholm et al. 1998; Gates et al.<br />

1992). The NBMB recommended further research into bison<br />

and disease ecology before planning management actions<br />

for the region (RAC 2001). In 1995, the Minister of Canadian<br />

Heritage formed the <strong>Bison</strong> Research and Containment Program<br />

(BRCP) to focus on disease containment and ecological and<br />

traditional knowledge research (RAC 2001). The Minister then<br />

created the Research Advisory Committee (RAC) to coordinate<br />

research activities under the BRCP (Chisholm et al. 1998). The<br />

RAC comprised a senior scientist appointed by Parks Canada,<br />

representatives from the Alberta and Northwest Territories<br />

governments, Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, and<br />

four aboriginal communities (Chisholm et al. 1998). During<br />

the mandated five year period (1996-2001), the BRCP funded<br />

projects to assess the prevalence and effects of the diseases<br />

on northern bison (Joly and Messier 2001a), and to investigate<br />

bison movements and the risk of disease transfer (Gates et<br />

al. 2001a). The RAC produced a future research agenda and<br />

budget for minimum research still required under the BRCP<br />

mandate (RAC 2001), but the programme was discontinued in<br />

2001. Many of the research needs identified by the RAC align<br />

with the recommendations outlined in the National Recovery<br />

Plan for Wood <strong>Bison</strong> prepared by the Wood <strong>Bison</strong> Recovery<br />

Team (Gates et al. 2001c). There remains considerable<br />

disagreement between federal and provincial governments<br />

and aboriginal interests concerning a long-term solution to<br />

the WBNP disease issue. Provincial governments support<br />

disease eradication, including aggressive intervention to<br />

achieve disease eradication within the national park. Parks<br />

Canada is concerned about the conservation and biological<br />

impacts associated with aggressive intervention. A technical<br />

workshop was convened in 2005 to explore the feasibility<br />

of removing diseased bison from the Greater Wood <strong>Buffalo</strong><br />

National Park region followed by a reintroduction of healthy<br />

bison (Shury et al. 2006), and there was unanimous agreement<br />

amongst participants that this option was technically feasible.<br />

The only subsequent management action undertaken at the<br />

time of writing was the implementation of a hunting season<br />

for the Hay-Zama herd in 2008-2009, intended, in part, to<br />

test disease status and to reduce the risk of infection with<br />

BTB and brucellosis by reducing population size and limiting<br />

range expansion towards infected populations (George<br />

Hamilton, Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, personal<br />

communication).<br />

36 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010<br />

5.4 Disease Management in Perspective<br />

A primary consideration regarding disease management<br />

in wild populations is determining when a disease is a<br />

conservation problem and whether intervention is warranted<br />

(Gilmour and Munro 1991). It can be argued that parasitism<br />

by disease organisms is a crucial ecological and evolutionary<br />

force in natural systems (Aguirre et al. 1995; Wobeser 2002).<br />

Classification of a pathogen as indigenous or exotic to a host<br />

species or ecosystem can influence whether a disease should<br />

be managed (Aguirre and Starkey 1994; Aguirre et al. 1995;<br />

National Park Service 2000). BTB and brucellosis are believed to<br />

have been transmitted to bison from domestic cattle. Therefore,<br />

management of these diseases in bison is warranted based on<br />

their exotic origins, as well as the threat they pose to domestic<br />

animals. However, many other pathogens have coevolved with<br />

bison and do not warrant veterinary intervention and should be<br />

managed in accordance with a natural system.<br />

The most significant diseases involving bison as wildlife affect<br />

a trinity of players (wildlife, humans, and domestic animals),<br />

and involve a tangle of transmission routes (Fischer 2008).<br />

Management of wildlife diseases has often been undertaken<br />

to minimise risks to humans and domestic animals (Nishi et<br />

al. 2002c; Wobeser 2002). Reportable disease management<br />

for agricultural purposes is typically based on the objective<br />

of eradicating the disease from a livestock population<br />

(Nishi et al. 2002c). The policy and legislative framework for<br />

eradicating reportable diseases in domestic animals is well<br />

developed, however, when applied to wildlife, the protocols<br />

used by agricultural agencies are usually not compatible with<br />

conservation goals (e.g., maintaining genetic diversity, minimal<br />

management intervention) (Nishi et al. 2002c). Increasingly, the<br />

broader conservation community is examining wildlife disease<br />

issues in the context of their impact on the viability of wild<br />

populations, conservation translocation programmes, and global<br />

biodiversity (Daszak and Cunningham 2000; Deem et al. 2001;<br />

Wobeser 2002). Creative disease-ecology research is needed,<br />

and an adaptive management framework is required for coping<br />

with diseases within a conservation context (Woodruff 1999).<br />

An evaluation of the disease management methods presently<br />

applied to bison populations is needed and could assist<br />

with development of novel conservation-appropriate policies<br />

and protocols for managing the health of free-ranging bison<br />

populations (Nishi et al. 2002c).<br />

Two emerging policy concepts being discussed to manage<br />

and control the transmission or distribution of disease at the<br />

domestic/wild animal interface include regionalisation and<br />

compartmentalisation (CFIA 2002; OIE 2008). Regionalisation<br />

offers one means of spatially identifying where disease control<br />

measures will occur on the land while compartmentalisation<br />

separates the control programmes of wild and domestic animals.