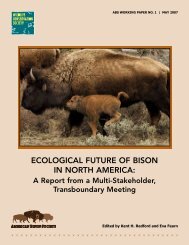

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

cattle at similar levels to S19 (Cheville et al. 1993). Doses of<br />

RB51 considered to be safe in cattle were found to induce<br />

endometritis, placentitis, and abortion in adult bison (Palmer<br />

et al. 1996). However, Roffe et al. (1999a) found RB51 had no<br />

significant adverse effects on bison calves. The safety and<br />

efficacy of RB51 in bison remains unclear but, nonetheless,<br />

it was provisionally approved for use in bison in the U.S. The<br />

vaccine is not recognised in Canada and vaccinated cattle are<br />

not allowed into the country (CFIA 2007). Every bison imported<br />

into Canada from the U.S. must be quarantined from the time of<br />

its importation into Canada until it proves negative to tests for<br />

brucellosis performed not less than 60 days after it was imported<br />

into Canada (CFIA 2007).<br />

Quarantine protocols have been developed for bison to<br />

progressively eliminate all animals exposed to brucellosis from<br />

a population (APHIS, USDA 2003; Nishi et al. 2002b). These<br />

protocols have been successful for eliminating brucellosis in<br />

wood bison through the Hook Lake project and are currently<br />

being attempted in the GYA (Aune and Linfield 2005; Nishi et al.<br />

2002b). Results from these two studies, and other case studies<br />

(HMSP, WCNP and EINP), have shown that brucellosis can be<br />

effectively eliminated from exposed populations with a high<br />

degree of certainty using test and slaughter protocols.<br />

5.1.6 Bovine tuberculosis<br />

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) is a chronic infectious disease caused<br />

by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis (Tessaro et al. 1990).<br />

The primary hosts for BTB are cattle and other bovid species,<br />

such as bison, water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), African buffalo<br />

(Syncerus caffer), and yak (Bos grunniens). Primary hosts are<br />

those species that are susceptible to infection and will maintain<br />

and propagate a disease indefinitely under natural conditions<br />

(Tessaro 1992). Other animals may contract a disease, but<br />

not perpetuate it under natural conditions; these species are<br />

secondary hosts. The bison is the only native species of wildlife<br />

in North America that can act as a true primary host for M. bovis<br />

(Tessaro 1992). Historical evidence indicates that BTB did not<br />

occur in bison prior to contact with infected domestic cattle<br />

(Tessaro 1992). Currently, the disease is only endemic in bison<br />

populations in and near WBNP, where it was introduced with<br />

translocated plains bison during the 1920s. BTB is primarily<br />

transmitted by inhalation and ingestion (Tessaro et al. 1990);<br />

the bacterium may also pass from mother to offspring via the<br />

placental connection, or through contaminated milk (FEARO<br />

1990; Tessaro 1992). The disease can affect the respiratory,<br />

digestive, urinary, nervous, skeletal, and reproductive systems<br />

(FEARO 1990; Tessaro et al. 1990). Once in the blood or lymph<br />

systems the bacterium may spread to any part of the host and<br />

establish chronic granulomatous lesions, which may become<br />

caseous, calcified, or necrotic (Radostits et al. 1994; Tessaro<br />

1992). This chronic disease is progressively debilitating to the<br />

host, and may cause reduced fertility and weakness; advanced<br />

cases are fatal (FEARO 1990). The disease manifests similarly<br />

in cattle and bison (Tessaro 1989; Tessaro et al. 1990). Both the<br />

U.S. and Canada perform nationwide surveillance of abattoir<br />

facilities to monitor BTB infection in cattle and domestic bison.<br />

There is no suitable vaccine available for BTB (FEARO 1990;<br />

CFIA 2000; APHIS USDA 2007). Every bison imported into<br />

Canada from the U.S. must be quarantined from the time of<br />

its importation into Canada until it proves negative to tests<br />

for BTB performed at least 60 days after it was imported into<br />

Canada (CFIA 2007). A quarantine protocol has been developed<br />

and an experimental project was attempted to salvage bison<br />

from a BTB exposed population (Nishi et al. 2002b). Although<br />

at first it appeared to be a successful tool for salvaging bison<br />

from an exposed herd, after 10 years, several of the salvaged<br />

animals expressed BTB, and in 2006 all salvaged animals were<br />

slaughtered (Nishi personal communication). There is some<br />

evidence that BTB can be treated in individual animals using<br />

long term dosing with antibiotics, but the duration of treatment,<br />

costs of therapy, and the need for containment make this<br />

option impractical for wildlife. The only definitive method for<br />

completely removing BTB from a herd is depopulation (CFIA<br />

2000; APHIS USDA 2005). The only alternative to depopulation<br />

is controlling the spatial distribution and prevalence of disease<br />

through a cooperative risk management approach involving all<br />

stakeholders. The basic prerequisites for effectively addressing<br />

risk management associated with BBTB in bison are teamwork,<br />

collaboration across professional disciplines, and respect for<br />

scientific and traditional ecological knowledge among technical<br />

and non technical stakeholders (Nishi et al. 2006). BTB can<br />

infect humans, but it is treatable with antimicrobial drugs.<br />

Human TB due to M. bovis has become very rare in countries<br />

with pasteurised milk and BTB eradication programmes.<br />

5.1.7 Bovine viral diarrhoea<br />

Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) is a pestivirus that infects a wide<br />

variety of ungulates (Loken 1995; Nettleston 1990). Serologic<br />

surveys in free-ranging and captive populations demonstrate<br />

prior exposure in more than 40 mammal species in North<br />

America (Nettleston 1990; Taylor et al. 1997). The suspected<br />

source of BVD in wild animals is direct contact with domestic<br />

livestock. Infections in wild ruminants, like cattle, are dependent<br />

upon the virulence of the isolate, immune status of the animal<br />

host, and the route of transmission. Infections in cattle are<br />

usually subclinical, but some infections may cause death<br />

or abortions in pregnant animals. Factors influencing the<br />

persistence of BVD include population size and density, herd<br />

behaviour, timing of reproduction, and survivorship of young<br />

(Campen et al. 2001).<br />

Positive serologic evidence was reported for blood samples<br />

from bison in the GYA (Taylor et al. 1997; Williams et al. 1993),<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 31