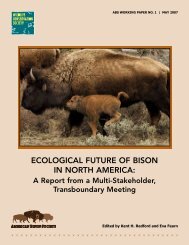

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

suitable landscapes for wild elk. TNC is another conservation<br />

organisation that has worked effectively with private landowners<br />

and government to protect biodiversity and establish protected<br />

areas through the use of land purchase and easements. TNC has<br />

incorporated bison on several of these landscapes as a means of<br />

providing ecosystem services.<br />

8.5.2.2 State/provincial and federal governance<br />

It is vital that governments (both elected officials and<br />

government agencies) be engaged in policymaking and<br />

legislation that support bison conservation. Government<br />

agencies typically establish processes within their statutory<br />

authority to evaluate and approve appropriate policy changes,<br />

and recommend congressional and legislative changes,<br />

necessary to conduct conservation. It will be necessary to<br />

employ all of the instruments and processes of governments<br />

to modify policies or legal statutes affecting bison conservation<br />

at state, provincial, and federal levels. Government agencies<br />

can also direct public funding and staff resources to support<br />

implementation of a restoration project, and develop the<br />

necessary interagency agreements to achieve conservation<br />

goals. It is necessary that elected officials, as representatives<br />

of the people, approve relevant policies, and to develop<br />

a legislative framework that supports bison restoration,<br />

by empowering the appropriate agencies to implement<br />

management strategies for conserving bison as publicly owned<br />

wildlife. For example, opportunities for bison restoration could<br />

be increased by linking them to existing policies for land use<br />

planning for ecological integrity. This will require building public<br />

support for policy changes and acceptance by respective<br />

constituencies that these governments serve, by using, for<br />

example, extensive outreach, public advocacy and education.<br />

It will also require educating and influencing key politicians and<br />

government officials with critical decision making roles.<br />

8.5.2.3 The private sector<br />

There is substantial evidence of a massive change in land<br />

ownership and shifting economies taking place in the Great<br />

Plains and West, as well as some multiple-generation ranchers<br />

who are entrepreneurial and ready for change (Powers 2001).<br />

This shift in land ownership, economies, and visions brings<br />

opportunities to create a new paradigm for managing rangelands<br />

of high conservation value. Private landowners could have a<br />

strong voice influencing elected and agency officials of the<br />

need for policy changes that provide incentives for, and remove<br />

barriers to, bison conservation on private lands. Therefore, there<br />

is currently a substantial opportunity to engage landowners to<br />

petition government for change.<br />

Privately owned bison managed on privately owned land<br />

typically present fewer regulatory obstacles than encountered<br />

78 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010<br />

in restoring wild bison. However, private herds are typically<br />

managed under a private property decision framework, which<br />

may not lead to a bison herd of conservation value. It is<br />

difficult to blend private property rights with the public trust<br />

framework for wildlife without negotiation and compromise.<br />

For effective cooperation, private owners of bison, or bison<br />

habitat, would have to be willing to sacrifice certain rights and<br />

submit to public review and scrutiny of operations. Government<br />

partners would also need to be sensitive to private property<br />

rights and the economic value of those rights for individuals or<br />

corporations willing to engage in bison conservation. Effective<br />

cooperation should include creative incentives, financial or<br />

other, to encourage the private entrepreneur to engage in<br />

bison conservation. For example, conservation easements<br />

compensate land-owners for transferring specific property<br />

rights. As noted earlier, a system for certifying producers who<br />

follow conservation guidelines in managing their bison herds<br />

may also provide an incentive.<br />

To increase opportunities for large-scale conservation of bison,<br />

there is a need for federal and state policy programmes that<br />

foster the creation of private (for-profit or non-profit) protected<br />

areas (PPAs). PPAs are one of the fastest growing forms of<br />

land and biodiversity conservation in the world (Mitchell 2005).<br />

However, unlike Australia and many countries in southern<br />

Africa, the U.S. and Canadian federal governments and state<br />

and provincial governments do not generally have policies<br />

specifically supporting the creation of PPAs. The IUCN has<br />

developed guidelines for, and explored policies and programmes<br />

that support, the creation of PPAs (Dudley 2008). The danger<br />

is that private bison reserves may quickly shift away from a<br />

conservation mission and devolve to “private game farms” for<br />

privately owned wildlife, for which most states have policies<br />

and regulations. In addition, private nature reserves may be<br />

vulnerable to change of ownership and subsequent shifts in their<br />

mission unless clear legal instruments are in place to protect<br />

conservation values. Clear guidelines for management and<br />

accountability for the long-term security of private protected<br />

areas is essential (Dudley 2008).<br />

8.5.2.4 Indigenous peoples<br />

Many protected landscapes and seascapes would not exist<br />

without the deeply rooted cultural and spiritual values held<br />

by the people that originally inhabited these places and who<br />

often continue to care for them (Mallarach 2008). Mallarach<br />

(2008) points out that safeguarding the integrity of traditional<br />

cultural and spiritual interactions with nature is vital to the<br />

protection, maintenance, and evolution of protected areas.<br />

Hence, protected landscapes and seascapes are the tangible<br />

result of the interaction of people and nature over time. In<br />

recent years there have been many important developments<br />

in conservation and protection of important landscapes on