American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The types of socioeconomic data relevant for ecological restoration<br />

planning will vary among locations across the continent. However,<br />

certain information is relevant for all landscapes. Detailed and<br />

current information on land use, including land use maps, is critical<br />

for assessing the impacts of habitat loss and trends. Development<br />

plans and targets for important resource sectors (agriculture,<br />

energy, and transportation) provide the basis for evaluating<br />

impacts of foreseeable change over time. Spatial information on<br />

land ownership and management authorities contribute to the<br />

identification of stakeholders and assessment of conservation<br />

potential.<br />

Loucks et al. (2004) provided the following list of socioeconomic<br />

variables useful for conservation planning. The list should be<br />

reviewed and customised for each project in consultation with<br />

local managers:<br />

1. Current patterns of land and resource use:<br />

Major land and resource uses (including forest,<br />

water, wildlife use, agriculture, extraction);<br />

Development plans and projected changes in land<br />

and resource use;<br />

Existing zoning regulations;<br />

Major existing and planned infrastructure (roads,<br />

dams, etc.);<br />

Existing protected areas.<br />

2. Governance and land/resource ownership and<br />

management:<br />

Political boundaries (provinces, districts);<br />

Land tenure (private, public, ancestral/communal<br />

areas);<br />

Agencies responsible for management of land/<br />

resource areas (e.g., forest, agriculture departments).<br />

3. Population data:<br />

Human population density and growth;<br />

Population centres;<br />

Migration patterns (in- and out-migration);<br />

Social characteristics: income, ethnicity,<br />

indigenous areas;<br />

Economic data;<br />

Economic growth and loss areas;<br />

Land prices;<br />

Potential values and opportunities for ecological<br />

services;<br />

Potential for incorporating natural assets into the<br />

local economy.<br />

108 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010<br />

4. Additional factors that affect biodiversity and<br />

potential for bison restoration:<br />

Access (e.g. roads, rivers, energy corridors, etc.);<br />

Trends in habitat conversion.<br />

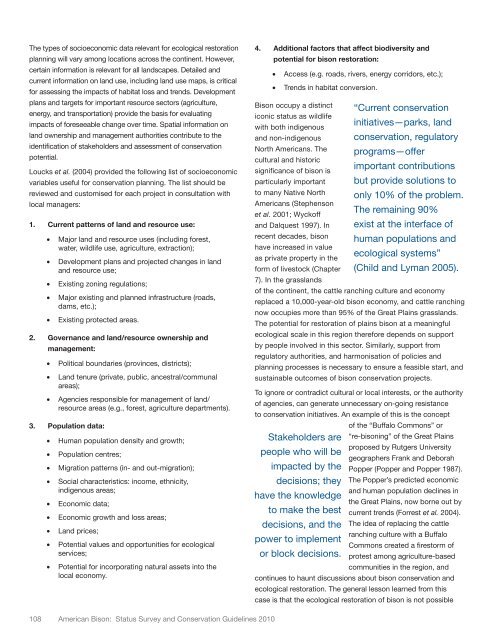

<strong>Bison</strong> occupy a distinct<br />

iconic status as wildlife<br />

with both indigenous<br />

and non-indigenous<br />

North <strong>American</strong>s. The<br />

cultural and historic<br />

significance of bison is<br />

particularly important<br />

to many Native North<br />

<strong>American</strong>s (Stephenson<br />

et al. 2001; Wyckoff<br />

and Dalquest 1997). In<br />

recent decades, bison<br />

have increased in value<br />

as private property in the<br />

form of livestock (Chapter<br />

7). In the grasslands<br />

of the continent, the cattle ranching culture and economy<br />

replaced a 10,000-year-old bison economy, and cattle ranching<br />

now occupies more than 95% of the Great Plains grasslands.<br />

The potential for restoration of plains bison at a meaningful<br />

ecological scale in this region therefore depends on support<br />

by people involved in this sector. Similarly, support from<br />

regulatory authorities, and harmonisation of policies and<br />

planning processes is necessary to ensure a feasible start, and<br />

sustainable outcomes of bison conservation projects.<br />

To ignore or contradict cultural or local interests, or the authority<br />

of agencies, can generate unnecessary on-going resistance<br />

to conservation initiatives. An example of this is the concept<br />

Stakeholders are<br />

people who will be<br />

impacted by the<br />

decisions; they<br />

have the knowledge<br />

to make the best<br />

decisions, and the<br />

power to implement<br />

or block decisions.<br />

“Current conservation<br />

initiatives—parks, land<br />

conservation, regulatory<br />

programs—offer<br />

important contributions<br />

but provide solutions to<br />

only 10% of the problem.<br />

The remaining 90%<br />

exist at the interface of<br />

human populations and<br />

ecological systems”<br />

(Child and Lyman 2005).<br />

of the “<strong>Buffalo</strong> Commons” or<br />

“re-bisoning” of the Great Plains<br />

proposed by Rutgers University<br />

geographers Frank and Deborah<br />

Popper (Popper and Popper 1987).<br />

The Popper’s predicted economic<br />

and human population declines in<br />

the Great Plains, now borne out by<br />

current trends (Forrest et al. 2004).<br />

The idea of replacing the cattle<br />

ranching culture with a <strong>Buffalo</strong><br />

Commons created a firestorm of<br />

protest among agriculture-based<br />

communities in the region, and<br />

continues to haunt discussions about bison conservation and<br />

ecological restoration. The general lesson learned from this<br />

case is that the ecological restoration of bison is not possible