American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

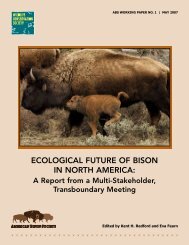

Chapter 10 Guidelines for Ecological<br />

Restoration of <strong>Bison</strong><br />

Lead Authors: C. Cormack Gates, Robert O. Stephenson, Peter J.P. Gogan, Curtis H. Freese, and Kyran Kunkel<br />

10.1 Introduction<br />

During Pre-Columbia times, bison had the widest distribution<br />

of any large herbivore in North America, ranging from the<br />

arid grasslands of northern Mexico to the extensive meadow<br />

systems of Interior Alaska (Chapters 2 and 7). Following the<br />

arrival of Europeans, the species experienced unparalleled range<br />

contraction and collapse of populations in the wild, primarily<br />

during the late 19 th Century (Isenberg 2000). Wild bison persisted<br />

in only two locations, south of Great Slave Lake in what is now<br />

Wood <strong>Buffalo</strong> National Park (about 300 individuals), and in the<br />

remote Pelican Valley in the Absaroka Mountains in the interior<br />

of Yellowstone National Park (YNP) (fewer than 30 individuals).<br />

The species was extirpated from the wild throughout the<br />

remainder of its original range. The <strong>American</strong> bison has achieved<br />

a remarkable numerical recovery, from approximately 500 at the<br />

end of the 19 th Century to about half a million animals today, of<br />

which 93% now exist under captive commercial propagation<br />

(Chapter 7). However, Sanderson et al. (2008) estimate that bison<br />

occupy less than 1% of their original range.<br />

Rarely do wildlife populations in North America achieve the<br />

full range of ecological interactions and social values existing<br />

prior to European settlement. The bison remains extirpated as<br />

wildlife and in the ecological sense from much of its original<br />

continental range. This is particularly true of the plains bison,<br />

for which few populations interact with the full suite of other<br />

native species and environmental limiting factors (Chapters 6<br />

and 7). In the absence of committed action by governments<br />

(including aboriginal governments), conservation organisations,<br />

and perhaps the commercial bison industry, the conservation of<br />

bison as a wild species is far from secure. The main challenges<br />

were described in earlier chapters of this volume and are<br />

summarised by Freese et al. (2007). They include anthropogenic<br />

selection and other types of intensive management of captive<br />

herds, small population size effects, issues related to exotic<br />

diseases, introgression of cattle genes, management under<br />

simplified agricultural production systems, and associated with<br />

this, widespread ecological extinction as an interactive species.<br />

Contemporary biological conservation is founded on the<br />

premise of maintaining the potential for ecological adaptation<br />

in viable populations in the wild (IUCN 2003; Secretariat of<br />

the Convention on Biological Diversity 1992; Soulé 1987), and<br />

maintaining interactive species (Soule et al. 2003). Viability<br />

relates to the capacity of a population to maintain itself without<br />

significant demographic or genetic manipulation by humans<br />

for the foreseeable future (Soulé 1987). For limiting factors,<br />

such as predation and seasonal resource limitation, adaptation<br />

requires interactions among species, between trophic levels,<br />

with physical elements of an ecosystem. These, and other<br />

interactions among individuals within a population (e.g., resource<br />

and mate competition), contribute to maintaining behavioural<br />

wildness, morphological and physiological adaptations, fitness,<br />

and genetic diversity. These factors enable a species to adapt,<br />

evolve, and persist in a natural setting without human support in<br />

the long term (Knowles et al. 1998).<br />

Viable, wild populations of bison, subject to the full range<br />

of natural limiting factors, are of pre-eminent importance to<br />

the long-term conservation, global security, and continued<br />

evolution of the species as wildlife. However, the availability<br />

of extensive ecosystems capable of sustaining large, free-<br />

roaming, ecologically interactive bison populations is limited.<br />

This is particularly true in the original range of plains bison in the<br />

southern agriculture-dominated regions of the continent, given<br />

the historical post-European settlement patterns of industrial and<br />

post-industrial society. Social and political systems that provide<br />

space and environmental conditions where bison can continue<br />

to exist as wildlife and evolve as a species, are severely limited.<br />

Innovative approaches need to be instigated in some locations<br />

to emulate, to the extent possible, the original ecological<br />

conditions, and to prevent domestication and small population-<br />

related deleterious effects such as those experienced by the<br />

European bison (Hartl and Pucek 1994; Prior 2005; Pucek et<br />

al. 2004). Currently, there is only one population of plains bison<br />

(YNP) and three populations of wood bison (Greater Wood<br />

<strong>Buffalo</strong> National Park, Mackenzie, and Nisling River) in North<br />

America that can be considered ecologically restored (thousands<br />

of individuals, large landscapes, all natural limiting factors<br />

present, minimal interference/management by humans).<br />

The conservation of <strong>American</strong> bison as wildlife would be<br />

significantly enhanced by establishing additional large<br />

populations to achieve landscape scale ecological restoration.<br />

This will require effective collaboration among a variety of<br />

stakeholders, whereby local actions, based upon social and<br />

scientific information, are coordinated with wider goals for<br />

species and ecosystem conservation. The bison was an<br />

<strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010 103