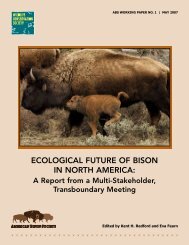

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

American Bison - Buffalo Field Campaign

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

to the decline of wood bison. The 1922 Orders in Council under<br />

the Forest Reserves and Parks Act established WBNP in an<br />

attempt to save wood bison from extinction (Boyd 2003; Gates<br />

et al. 2001a; 2001b; Soper 1941).<br />

8.2.1.3 Policy development in Mexico<br />

Historically, bison were present in five states in northern Mexico,<br />

but until recently existed in the wild only in the borderlands<br />

between the Janos region of Chihuahua and south-western<br />

New Mexico (List et al. 2007). Mexico first included bison on<br />

its red-list of endangered species in 1994. The most recent<br />

version (SEMARNAT 2002) specifically lists bison in the Janos-<br />

Hildago herd as “endangered wildlife”. Although the population<br />

is afforded legal protection in Mexico, it is considered livestock<br />

when it ranges into New Mexico. See section 8.5.5.3 for more<br />

details on this herd.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> conservation in Mexico has primarily been implemented<br />

through federal programmes; status has not yet been<br />

established under state legislation. The National Ministry of<br />

Environment (SEMARNAT 2002) managed bison for many<br />

years. Recently the responsibility for priority species, including<br />

bison, was transferred to the National Commission of Protected<br />

Natural Areas. The Institute of Ecology of the National<br />

University of Mexico is advocating legal protection of the herd<br />

in both countries, including protection under international<br />

treaties on migratory wildlife species between Mexico and<br />

the U.S. The IUCN <strong>Bison</strong> Specialist Group (BSG) strongly<br />

encourages this protective action and other efforts to restore<br />

plains bison to the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands.<br />

8.2.2 Plains bison conservation by the private sector<br />

Private sector conservation efforts can be categorised into two<br />

non-exclusive groups: 1) private citizens interested primarily<br />

in commercial production of bison and secondarily in bison<br />

conservation; and 2) private conservation groups interested<br />

in conserving bison as wildlife. The former do not typically<br />

have formal constitutions mandating conservation, while the<br />

latter institutions typically do. Legislation, regulations, rules,<br />

and policies affecting captive herds owned by these sectors<br />

are similar to domestic livestock, focusing on transport, trade,<br />

export, import, animal health, and use of public grazing lands.<br />

Notably, Turner Enterprises has been involved in the development<br />

of production herds on 14 large ranches in the U.S., the largest<br />

number of plains bison owned and managed by a single owner.<br />

<strong>Bison</strong> are managed with low management inputs similar to<br />

many public conservation herds. Notably, the Castle Rock herd<br />

on Vermejo Park Ranch in New Mexico is derived from stock<br />

translocated during the 1930s from YNP and showing no evidence<br />

of cattle gene introgression. Although some privately owned<br />

herds may be valuable for conservation, there is no precedent for<br />

64 <strong>American</strong> <strong>Bison</strong>: Status Survey and Conservation Guidelines 2010<br />

assessing their long-term contribution to conservation of bison<br />

as wildlife. Recently, the Wildlife Conservation Society developed<br />

an evaluation matrix that helps identify the key characteristics<br />

and possible management adjustments that would be necessary<br />

for privately owned herds to contribute to bison conservation<br />

(Sanderson et al. 2008). This matrix is still evolving and was<br />

recently tested among a small producer group to refine and<br />

improve its application. Population and genetic management<br />

guidelines presented earlier in this document may also be useful<br />

for guiding private producers toward managing their herds in<br />

support of conservation. However, a system for certifying herds<br />

for conservation management would be required to ensure that<br />

guidelines are followed.<br />

Several non-governmental organisations (NGO), particularly<br />

The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Nature Conservancy of<br />

Canada (NCC), <strong>American</strong> Prairie Foundation (APF), and the<br />

World Wildlife Fund (WWF) have been active in developing<br />

conservation herds. More information on their initiatives can be<br />

found in section 8.5.5.4.<br />

8.2.3 Conservation efforts by tribes and First Nations<br />

Many North <strong>American</strong> Native Peoples have strong cultural,<br />

spiritual, and symbolic relationships with bison (Notzke 1994;<br />

Zontek 2007). Some tribes believe that because the animals<br />

once sustained their Indian way of life, they, in turn, must help<br />

the bison to sustain their place on the earth. The conservation<br />

of wild bison includes the intangible values these tribes hold for<br />

bison. Values vary greatly between tribes, and in some cases,<br />

even between members of the same tribe. Some tribal people<br />

believe that the status of the bison reflects the treatment of North<br />

<strong>American</strong> Indians. Interest in preserving the cultural significance<br />

of bison, and in restoring cultural connections to the species, can<br />

be important incentives for Native governments and communities<br />

to participate in bison conservation (Notzke 1994; Zontek 2007).<br />

Some tribal bison managers consider all bison as wild animals<br />

regardless of the source of stock, genetic introgression from<br />

cattle, or domestication history. This can be the basis for conflict<br />

with conservation biologists who apply biological criteria when<br />

evaluating the conservation merit of a herd. Tribal governments<br />

commonly operate under challenging circumstances. Political<br />

views can vary between succeeding tribal administrations,<br />

creating unstable policies that can affect bison management and<br />

conservation practices. Numerous Native Tribes own or influence<br />

the management of a significant land base that has the potential<br />

to sustain large bison herds. However, there has yet to be a<br />

systematic survey of the number of herds or the distribution of<br />

bison under Native management—a task of sufficient magnitude<br />

and complexity to exceed the scope of this review.<br />

The potential for tribes to participate in bison restoration<br />

is improving with the development of tribal game and fish