Unit A Reproduction

Unit A Reproduction

Unit A Reproduction

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

FIGHTING HUNTINGTON’S DISEASE<br />

Genetically modified mice are helping Vancouver scientists learn<br />

more about this deadly genetic disease.<br />

Tech<br />

CONNECT<br />

Would you want to know right away if<br />

you carried the gene? Would you rather<br />

wait and see if you developed the<br />

symptoms? Children of people with<br />

Huntington’s disease must ask themselves<br />

these questions. Huntington’s disease is<br />

a disease of the nervous system that is<br />

characterized by loss of memory,<br />

reasoning, and judgment, as well as<br />

involuntary jerky movements of the<br />

limbs, head, and neck. The onset of<br />

Huntington’s disease is usually between<br />

30 and 50 years of age, and because<br />

there is currently no cure, death occurs<br />

from complications 10 to 15 years after<br />

the onset of the disease. People with<br />

Huntington’s disease usually die from<br />

falls or choking.<br />

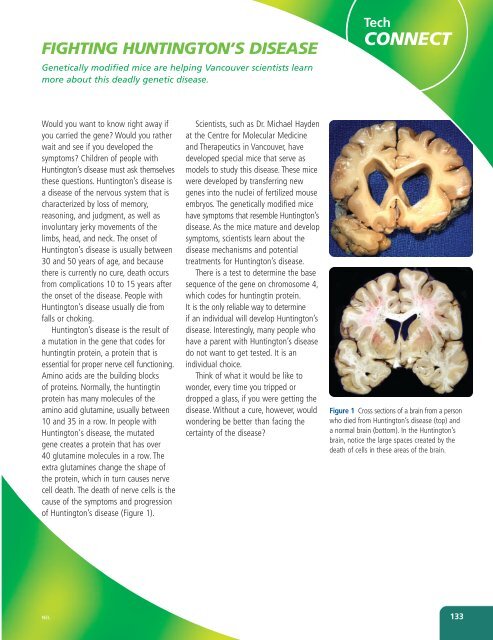

Huntington’s disease is the result of<br />

a mutation in the gene that codes for<br />

huntingtin protein, a protein that is<br />

essential for proper nerve cell functioning.<br />

Amino acids are the building blocks<br />

of proteins. Normally, the huntingtin<br />

protein has many molecules of the<br />

amino acid glutamine, usually between<br />

10 and 35 in a row. In people with<br />

Huntington's disease, the mutated<br />

gene creates a protein that has over<br />

40 glutamine molecules in a row. The<br />

extra glutamines change the shape of<br />

the protein, which in turn causes nerve<br />

cell death. The death of nerve cells is the<br />

cause of the symptoms and progression<br />

of Huntington’s disease (Figure 1).<br />

Scientists, such as Dr. Michael Hayden<br />

at the Centre for Molecular Medicine<br />

and Therapeutics in Vancouver, have<br />

developed special mice that serve as<br />

models to study this disease. These mice<br />

were developed by transferring new<br />

genes into the nuclei of fertilized mouse<br />

embryos. The genetically modified mice<br />

have symptoms that resemble Huntington’s<br />

disease. As the mice mature and develop<br />

symptoms, scientists learn about the<br />

disease mechanisms and potential<br />

treatments for Huntington’s disease.<br />

There is a test to determine the base<br />

sequence of the gene on chromosome 4,<br />

which codes for huntingtin protein.<br />

It is the only reliable way to determine<br />

if an individual will develop Huntington’s<br />

disease. Interestingly, many people who<br />

have a parent with Huntington’s disease<br />

do not want to get tested. It is an<br />

individual choice.<br />

Think of what it would be like to<br />

wonder, every time you tripped or<br />

dropped a glass, if you were getting the<br />

disease. Without a cure, however, would<br />

wondering be better than facing the<br />

certainty of the disease?<br />

Figure 1 Cross sections of a brain from a person<br />

who died from Huntington’s disease (top) and<br />

a normal brain (bottom). In the Huntington’s<br />

brain, notice the large spaces created by the<br />

death of cells in these areas of the brain.<br />

NEL<br />

133