Climate change futures: health, ecological and economic dimensions

Climate change futures: health, ecological and economic dimensions

Climate change futures: health, ecological and economic dimensions

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THE PROBLEM:<br />

CLIMATE IS CHANGING, FAST<br />

The proposition that climate <strong>change</strong> poses a threat<br />

because of an enhanced greenhouse effect inevitably<br />

begs questions. Without greenhouse gases such as<br />

CO 2<br />

trapping heat (by absorbing long-wave length<br />

radiation from the earth’s surface), the planet would be<br />

so cold that life as we know it would be impossible.<br />

For more than two million years, Earth has alternated<br />

between two states: long periods of icy cold interrupted<br />

by relatively short respites of warmth. During glacial<br />

times, the polar ice caps <strong>and</strong> Alpine glaciers<br />

grow; during the interglacial periods, the North Polar<br />

cap shrinks, as do Alpine glaciers.<br />

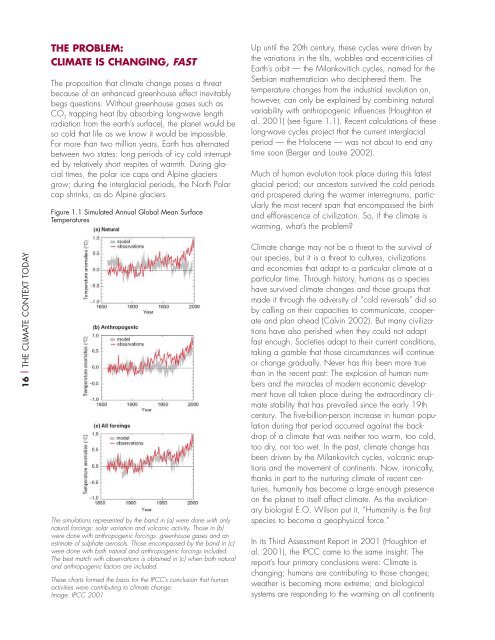

Figure 1.1 Simulated Annual Global Mean Surface<br />

Temperatures<br />

Up until the 20th century, these cycles were driven by<br />

the variations in the tilts, wobbles <strong>and</strong> eccentricities of<br />

Earth’s orbit — the Milankovitich cycles, named for the<br />

Serbian mathematician who deciphered them. The<br />

temperature <strong>change</strong>s from the industrial revolution on,<br />

however, can only be explained by combining natural<br />

variability with anthropogenic influences (Houghton et<br />

al. 2001) (see figure 1.1). Recent calculations of these<br />

long-wave cycles project that the current interglacial<br />

period — the Holocene — was not about to end any<br />

time soon (Berger <strong>and</strong> Loutre 2002).<br />

Much of human evolution took place during this latest<br />

glacial period; our ancestors survived the cold periods<br />

<strong>and</strong> prospered during the warmer interregnums, particularly<br />

the most recent span that encompassed the birth<br />

<strong>and</strong> efflorescence of civilization. So, if the climate is<br />

warming, what’s the problem?<br />

16 | THE CLIMATE CONTEXT TODAY<br />

The simulations represented by the b<strong>and</strong> in (a) were done with only<br />

natural forcings: solar variation <strong>and</strong> volcanic activity. Those in (b)<br />

were done with anthropogenic forcings: greenhouse gases <strong>and</strong> an<br />

estimate of sulphate aerosols. Those encompassed by the b<strong>and</strong> in (c)<br />

were done with both natural <strong>and</strong> anthropogenic forcings included.<br />

The best match with observations is obtained in (c) when both natural<br />

<strong>and</strong> anthropogenic factors are included.<br />

These charts formed the basis for the IPCC’s conclusion that human<br />

activities were contributing to climate <strong>change</strong>.<br />

Image: IPCC 2001<br />

<strong>Climate</strong> <strong>change</strong> may not be a threat to the survival of<br />

our species, but it is a threat to cultures, civilizations<br />

<strong>and</strong> economies that adapt to a particular climate at a<br />

particular time. Through history, humans as a species<br />

have survived climate <strong>change</strong>s <strong>and</strong> those groups that<br />

made it through the adversity of “cold reversals” did so<br />

by calling on their capacities to communicate, cooperate<br />

<strong>and</strong> plan ahead (Calvin 2002). But many civilizations<br />

have also perished when they could not adapt<br />

fast enough. Societies adapt to their current conditions,<br />

taking a gamble that those circumstances will continue<br />

or <strong>change</strong> gradually. Never has this been more true<br />

than in the recent past: The explosion of human numbers<br />

<strong>and</strong> the miracles of modern <strong>economic</strong> development<br />

have all taken place during the extraordinary climate<br />

stability that has prevailed since the early 19th<br />

century. The five-billion-person increase in human population<br />

during that period occurred against the backdrop<br />

of a climate that was neither too warm, too cold,<br />

too dry, nor too wet. In the past, climate <strong>change</strong> has<br />

been driven by the Milankovitch cycles, volcanic eruptions<br />

<strong>and</strong> the movement of continents. Now, ironically,<br />

thanks in part to the nurturing climate of recent centuries,<br />

humanity has become a large enough presence<br />

on the planet to itself affect climate. As the evolutionary<br />

biologist E.O. Wilson put it, “Humanity is the first<br />

species to become a geophysical force.”<br />

In its Third Assessment Report in 2001 (Houghton et<br />

al. 2001), the IPCC came to the same insight. The<br />

report’s four primary conclusions were: <strong>Climate</strong> is<br />

changing; humans are contributing to those <strong>change</strong>s;<br />

weather is becoming more extreme; <strong>and</strong> biological<br />

systems are responding to the warming on all continents