Climate change futures: health, ecological and economic dimensions

Climate change futures: health, ecological and economic dimensions

Climate change futures: health, ecological and economic dimensions

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

262 deaths in 2003; 7,470 cases <strong>and</strong> 88 deaths in<br />

2004. The falling death rate suggests that the virulence<br />

of this emerging disease in North Americas is<br />

diminishing over time.<br />

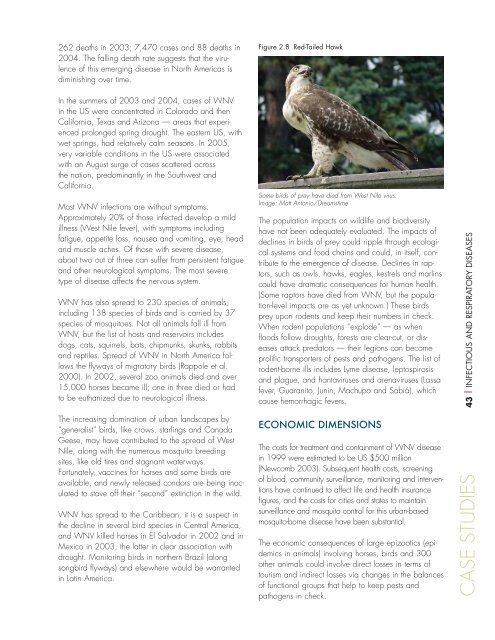

Figure 2.8 Red-Tailed Hawk<br />

In the summers of 2003 <strong>and</strong> 2004, cases of WNV<br />

in the US were concentrated in Colorado <strong>and</strong> then<br />

California, Texas <strong>and</strong> Arizona — areas that experienced<br />

prolonged spring drought. The eastern US, with<br />

wet springs, had relatively calm seasons. In 2005,<br />

very variable conditions in the US were associated<br />

with an August surge of cases scattered across<br />

the nation, predominantly in the Southwest <strong>and</strong><br />

California.<br />

Most WNV infections are without symptoms.<br />

Approximately 20% of those infected develop a mild<br />

illness (West Nile fever), with symptoms including<br />

fatigue, appetite loss, nausea <strong>and</strong> vomiting, eye, head<br />

<strong>and</strong> muscle aches. Of those with severe disease,<br />

about two out of three can suffer from persistent fatigue<br />

<strong>and</strong> other neurological symptoms. The most severe<br />

type of disease affects the nervous system.<br />

WNV has also spread to 230 species of animals,<br />

including 138 species of birds <strong>and</strong> is carried by 37<br />

species of mosquitoes. Not all animals fall ill from<br />

WNV, but the list of hosts <strong>and</strong> reservoirs includes<br />

dogs, cats, squirrels, bats, chipmunks, skunks, rabbits<br />

<strong>and</strong> reptiles. Spread of WNV in North America follows<br />

the flyways of migratory birds (Rappole et al.<br />

2000). In 2002, several zoo animals died <strong>and</strong> over<br />

15,000 horses became ill; one in three died or had<br />

to be euthanized due to neurological illness.<br />

Some birds of prey have died from West Nile virus.<br />

Image: Matt Antonio/Dreamstime<br />

The population impacts on wildlife <strong>and</strong> biodiversity<br />

have not been adequately evaluated. The impacts of<br />

declines in birds of prey could ripple through <strong>ecological</strong><br />

systems <strong>and</strong> food chains <strong>and</strong> could, in itself, contribute<br />

to the emergence of disease. Declines in raptors,<br />

such as owls, hawks, eagles, kestrels <strong>and</strong> marlins<br />

could have dramatic consequences for human <strong>health</strong>.<br />

(Some raptors have died from WNV, but the population-level<br />

impacts are as yet unknown.) These birds<br />

prey upon rodents <strong>and</strong> keep their numbers in check.<br />

When rodent populations “explode” — as when<br />

floods follow droughts, forests are clear-cut, or diseases<br />

attack predators — their legions can become<br />

prolific transporters of pests <strong>and</strong> pathogens. The list of<br />

rodent-borne ills includes Lyme disease, leptospirosis<br />

<strong>and</strong> plague, <strong>and</strong> hantaviruses <strong>and</strong> arenaviruses (Lassa<br />

fever, Guaranito, Junin, Machupo <strong>and</strong> Sabiá), which<br />

cause hemorrhagic fevers.<br />

43 | INFECTIOUS AND RESPIRATORY DISEASES<br />

The increasing domination of urban l<strong>and</strong>scapes by<br />

“generalist” birds, like crows, starlings <strong>and</strong> Canada<br />

Geese, may have contributed to the spread of West<br />

Nile, along with the numerous mosquito breeding<br />

sites, like old tires <strong>and</strong> stagnant waterways.<br />

Fortunately, vaccines for horses <strong>and</strong> some birds are<br />

available, <strong>and</strong> newly released condors are being inoculated<br />

to stave off their “second” extinction in the wild.<br />

WNV has spread to the Caribbean, it is a suspect in<br />

the decline in several bird species in Central America,<br />

<strong>and</strong> WNV killed horses in El Salvador in 2002 <strong>and</strong> in<br />

Mexico in 2003, the latter in clear association with<br />

drought. Monitoring birds in northern Brazil (along<br />

songbird flyways) <strong>and</strong> elsewhere would be warranted<br />

in Latin America.<br />

ECONOMIC DIMENSIONS<br />

The costs for treatment <strong>and</strong> containment of WNV disease<br />

in 1999 were estimated to be US $500 million<br />

(Newcomb 2003). Subsequent <strong>health</strong> costs, screening<br />

of blood, community surveillance, monitoring <strong>and</strong> interventions<br />

have continued to affect life <strong>and</strong> <strong>health</strong> insurance<br />

figures, <strong>and</strong> the costs for cities <strong>and</strong> states to maintain<br />

surveillance <strong>and</strong> mosquito control for this urban-based<br />

mosquito-borne disease have been substantial.<br />

The <strong>economic</strong> consequences of large epizootics (epidemics<br />

in animals) involving horses, birds <strong>and</strong> 300<br />

other animals could involve direct losses in terms of<br />

tourism <strong>and</strong> indirect losses via <strong>change</strong>s in the balances<br />

of functional groups that help to keep pests <strong>and</strong><br />

pathogens in check.<br />

CASE STUDIES