Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

70<br />

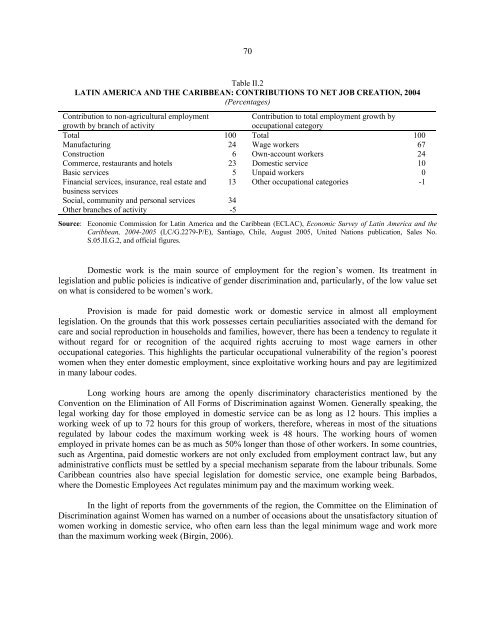

Table II.2<br />

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: CONTRIBUTIONS TO NET JOB CREATION, 2004<br />

(Percentages)<br />

Contribution to non-agricultural employment<br />

growth by branch of activity<br />

Contribution to total employment growth by<br />

occupational category<br />

Total 100 Total 100<br />

Manufactur<strong>in</strong>g 24 Wage workers 67<br />

Construction 6 Own-account workers 24<br />

Commerce, restaurants <strong>and</strong> hotels 23 Domestic service 10<br />

Basic services 5 Unpaid workers 0<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ancial services, <strong>in</strong>surance, real estate <strong>and</strong> 13 O<strong>the</strong>r occupational categories -1<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess services<br />

Social, community <strong>and</strong> personal services 34<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r branches of activity -5<br />

Source: Economic Commission for Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> (ECLAC), Economic Survey of Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong>, 2004-2005 (LC/G.2279-P/E), Santiago, Chile, August 2005, United Nations publication, Sales No.<br />

S.05.II.G.2, <strong>and</strong> official figures.<br />

Domestic work is <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> source of employment for <strong>the</strong> region’s women. Its treatment <strong>in</strong><br />

legislation <strong>and</strong> public policies is <strong>in</strong>dicative of gender discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong>, particularly, of <strong>the</strong> low value set<br />

on what is considered to be women’s work.<br />

Provision is made for paid domestic work or domestic service <strong>in</strong> almost all employment<br />

legislation. On <strong>the</strong> grounds that this work possesses certa<strong>in</strong> peculiarities associated with <strong>the</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> for<br />

care <strong>and</strong> social reproduction <strong>in</strong> households <strong>and</strong> families, however, <strong>the</strong>re has been a tendency to regulate it<br />

without regard for or recognition of <strong>the</strong> acquired rights accru<strong>in</strong>g to most wage earners <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

occupational categories. This highlights <strong>the</strong> particular occupational vulnerability of <strong>the</strong> region’s poorest<br />

women when <strong>the</strong>y enter domestic employment, s<strong>in</strong>ce exploitative work<strong>in</strong>g hours <strong>and</strong> pay are legitimized<br />

<strong>in</strong> many labour codes.<br />

Long work<strong>in</strong>g hours are among <strong>the</strong> openly discrim<strong>in</strong>atory characteristics mentioned by <strong>the</strong><br />

Convention on <strong>the</strong> Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of All Forms of Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>Women</strong>. Generally speak<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong><br />

legal work<strong>in</strong>g day for those employed <strong>in</strong> domestic service can be as long as 12 hours. This implies a<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g week of up to 72 hours for this group of workers, <strong>the</strong>refore, whereas <strong>in</strong> most of <strong>the</strong> situations<br />

regulated by labour codes <strong>the</strong> maximum work<strong>in</strong>g week is 48 hours. The work<strong>in</strong>g hours of women<br />

employed <strong>in</strong> private homes can be as much as 50% longer than those of o<strong>the</strong>r workers. In some countries,<br />

such as Argent<strong>in</strong>a, paid domestic workers are not only excluded from employment contract law, but any<br />

adm<strong>in</strong>istrative conflicts must be settled by a special mechanism separate from <strong>the</strong> labour tribunals. Some<br />

<strong>Caribbean</strong> countries also have special legislation for domestic service, one example be<strong>in</strong>g Barbados,<br />

where <strong>the</strong> Domestic Employees Act regulates m<strong>in</strong>imum pay <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> maximum work<strong>in</strong>g week.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> light of reports from <strong>the</strong> governments of <strong>the</strong> region, <strong>the</strong> Committee on <strong>the</strong> Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of<br />

Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>Women</strong> has warned on a number of occasions about <strong>the</strong> unsatisfactory situation of<br />

women work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> domestic service, who often earn less than <strong>the</strong> legal m<strong>in</strong>imum wage <strong>and</strong> work more<br />

than <strong>the</strong> maximum work<strong>in</strong>g week (Birg<strong>in</strong>, 2006).