Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

72<br />

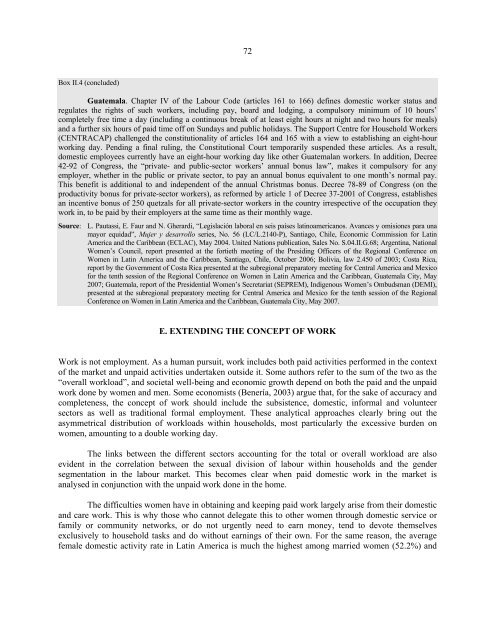

Box II.4 (concluded)<br />

Guatemala. Chapter IV of <strong>the</strong> Labour Code (articles 161 to 166) def<strong>in</strong>es domestic worker status <strong>and</strong><br />

regulates <strong>the</strong> rights of such workers, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g pay, board <strong>and</strong> lodg<strong>in</strong>g, a compulsory m<strong>in</strong>imum of 10 hours’<br />

completely free time a day (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a cont<strong>in</strong>uous break of at least eight hours at night <strong>and</strong> two hours for meals)<br />

<strong>and</strong> a fur<strong>the</strong>r six hours of paid time off on Sundays <strong>and</strong> public holidays. The Support Centre for Household Workers<br />

(CENTRACAP) challenged <strong>the</strong> constitutionality of articles 164 <strong>and</strong> 165 with a view to establish<strong>in</strong>g an eight-hour<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g day. Pend<strong>in</strong>g a f<strong>in</strong>al rul<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> Constitutional Court temporarily suspended <strong>the</strong>se articles. As a result,<br />

domestic employees currently have an eight-hour work<strong>in</strong>g day like o<strong>the</strong>r Guatemalan workers. In addition, Decree<br />

42-92 of Congress, <strong>the</strong> “private- <strong>and</strong> public-sector workers’ annual bonus law”, makes it compulsory for any<br />

employer, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> public or private sector, to pay an annual bonus equivalent to one month’s normal pay.<br />

This benefit is additional to <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent of <strong>the</strong> annual Christmas bonus. Decree 78-89 of Congress (on <strong>the</strong><br />

productivity bonus for private-sector workers), as reformed by article 1 of Decree 37-2001 of Congress, establishes<br />

an <strong>in</strong>centive bonus of 250 quetzals for all private-sector workers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country irrespective of <strong>the</strong> occupation <strong>the</strong>y<br />

work <strong>in</strong>, to be paid by <strong>the</strong>ir employers at <strong>the</strong> same time as <strong>the</strong>ir monthly wage.<br />

Source: L. Pautassi, E. Faur <strong>and</strong> N. Gherardi, “Legislación laboral en seis países lat<strong>in</strong>oamericanos. Avances y omisiones para una<br />

mayor equidad”, Mujer y desarrollo series, No. 56 (LC/L.2140-P), Santiago, Chile, Economic Commission for Lat<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> (ECLAC), May 2004. United Nations publication, Sales No. S.04.II.G.68; Argent<strong>in</strong>a, National<br />

<strong>Women</strong>’s Council, report presented at <strong>the</strong> fortieth meet<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> Presid<strong>in</strong>g Officers of <strong>the</strong> Regional Conference on<br />

<strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>, Santiago, Chile, October 2006; Bolivia, law 2.450 of 2003; Costa Rica,<br />

report by <strong>the</strong> Government of Costa Rica presented at <strong>the</strong> subregional preparatory meet<strong>in</strong>g for Central <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> Mexico<br />

for <strong>the</strong> tenth session of <strong>the</strong> Regional Conference on <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>, Guatemala City, May<br />

2007; Guatemala, report of <strong>the</strong> Presidential <strong>Women</strong>’s Secretariat (SEPREM), Indigenous <strong>Women</strong>’s Ombudsman (DEMI),<br />

presented at <strong>the</strong> subregional preparatory meet<strong>in</strong>g for Central <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> Mexico for <strong>the</strong> tenth session of <strong>the</strong> Regional<br />

Conference on <strong>Women</strong> <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong>, Guatemala City, May 2007.<br />

E. EXTENDING THE CONCEPT OF WORK<br />

Work is not employment. As a human pursuit, work <strong>in</strong>cludes both paid activities performed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context<br />

of <strong>the</strong> market <strong>and</strong> unpaid activities undertaken outside it. Some authors refer to <strong>the</strong> sum of <strong>the</strong> two as <strong>the</strong><br />

“overall workload”, <strong>and</strong> societal well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> economic growth depend on both <strong>the</strong> paid <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> unpaid<br />

work done by women <strong>and</strong> men. Some economists (Benería, 2003) argue that, for <strong>the</strong> sake of accuracy <strong>and</strong><br />

completeness, <strong>the</strong> concept of work should <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> subsistence, domestic, <strong>in</strong>formal <strong>and</strong> volunteer<br />

sectors as well as traditional formal employment. These analytical approaches clearly br<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong><br />

asymmetrical distribution of workloads with<strong>in</strong> households, most particularly <strong>the</strong> excessive burden on<br />

women, amount<strong>in</strong>g to a double work<strong>in</strong>g day.<br />

The l<strong>in</strong>ks between <strong>the</strong> different sectors account<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong> total or overall workload are also<br />

evident <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> correlation between <strong>the</strong> sexual division of labour with<strong>in</strong> households <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> gender<br />

segmentation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> labour market. This becomes clear when paid domestic work <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> market is<br />

analysed <strong>in</strong> conjunction with <strong>the</strong> unpaid work done <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> home.<br />

The difficulties women have <strong>in</strong> obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> keep<strong>in</strong>g paid work largely arise from <strong>the</strong>ir domestic<br />

<strong>and</strong> care work. This is why those who cannot delegate this to o<strong>the</strong>r women through domestic service or<br />

family or community networks, or do not urgently need to earn money, tend to devote <strong>the</strong>mselves<br />

exclusively to household tasks <strong>and</strong> do without earn<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>the</strong>ir own. For <strong>the</strong> same reason, <strong>the</strong> average<br />

female domestic activity rate <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> is much <strong>the</strong> highest among married women (52.2%) <strong>and</strong>