Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

Women in Latin America and the Caribbean - Cepal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

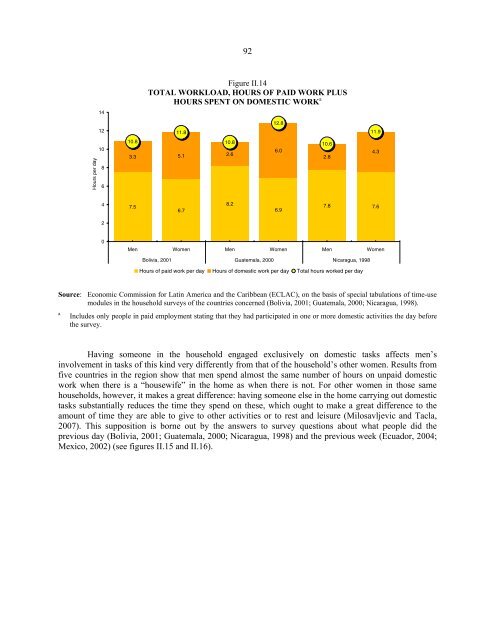

92<br />

14<br />

Figure II.14<br />

TOTAL WORKLOAD, HOURS OF PAID WORK PLUS<br />

HOURS SPENT ON DOMESTIC WORK a<br />

12<br />

11.8<br />

12.8<br />

11.9<br />

Hours per day<br />

10<br />

8<br />

6<br />

10.8<br />

10.8<br />

3.3 5.1 2.6<br />

6.0<br />

10.6<br />

2.8<br />

4.3<br />

4<br />

7.5<br />

6.7<br />

8.2<br />

6.9<br />

7.8 7.6<br />

2<br />

0<br />

Men <strong>Women</strong> Men <strong>Women</strong> Men <strong>Women</strong><br />

Bolivia, 2001 Guatemala, 2000 Nicaragua, 1998<br />

Hours of paid work per day Hours of domestic work per day Total hours worked per day<br />

Source: Economic Commission for Lat<strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Caribbean</strong> (ECLAC), on <strong>the</strong> basis of special tabulations of time-use<br />

modules <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> household surveys of <strong>the</strong> countries concerned (Bolivia, 2001; Guatemala, 2000; Nicaragua, 1998).<br />

a<br />

Includes only people <strong>in</strong> paid employment stat<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>y had participated <strong>in</strong> one or more domestic activities <strong>the</strong> day before<br />

<strong>the</strong> survey.<br />

Hav<strong>in</strong>g someone <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> household engaged exclusively on domestic tasks affects men’s<br />

<strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> tasks of this k<strong>in</strong>d very differently from that of <strong>the</strong> household’s o<strong>the</strong>r women. Results from<br />

five countries <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> region show that men spend almost <strong>the</strong> same number of hours on unpaid domestic<br />

work when <strong>the</strong>re is a “housewife” <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> home as when <strong>the</strong>re is not. For o<strong>the</strong>r women <strong>in</strong> those same<br />

households, however, it makes a great difference: hav<strong>in</strong>g someone else <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> home carry<strong>in</strong>g out domestic<br />

tasks substantially reduces <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong>y spend on <strong>the</strong>se, which ought to make a great difference to <strong>the</strong><br />

amount of time <strong>the</strong>y are able to give to o<strong>the</strong>r activities or to rest <strong>and</strong> leisure (Milosavljevic <strong>and</strong> Tacla,<br />

2007). This supposition is borne out by <strong>the</strong> answers to survey questions about what people did <strong>the</strong><br />

previous day (Bolivia, 2001; Guatemala, 2000; Nicaragua, 1998) <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> previous week (Ecuador, 2004;<br />

Mexico, 2002) (see figures II.15 <strong>and</strong> II.16).