- Page 1 and 2:

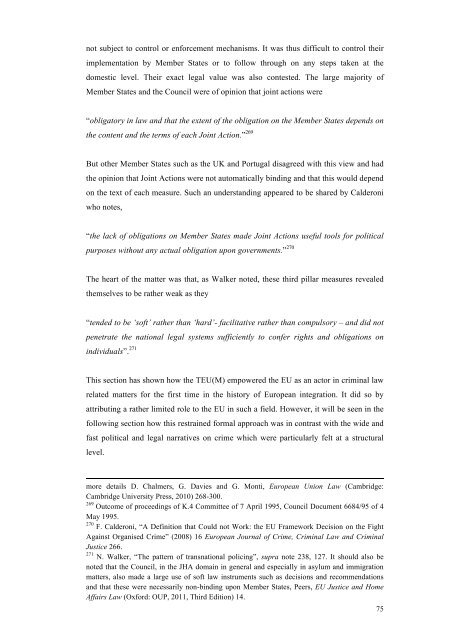

The London School of Economics and

- Page 3 and 4:

Abstract This thesis addresses the

- Page 5 and 6:

However, the journey of writing thi

- Page 7 and 8:

3. The scope of intervention: the e

- Page 9 and 10:

4. The emergence and development of

- Page 11 and 12:

Introduction: The nature of Europea

- Page 13 and 14:

This dissertation seeks to advance

- Page 15 and 16:

account as a reference. Indeed, sev

- Page 17 and 18:

Whilst the distinctive criteria of

- Page 19 and 20:

it makes sense to consider the doma

- Page 21 and 22:

creation of summary offences tried

- Page 23 and 24: want to be talking about a simple a

- Page 25 and 26: contemporary societies that primari

- Page 27 and 28: influence on Member States to intro

- Page 29 and 30: But what defines these Euro-crimes

- Page 31 and 32: significantly broader range of crim

- Page 33 and 34: legal orders that punish more sever

- Page 35 and 36: enforcement agencies were keen to e

- Page 37 and 38: framed. 98 The principle of direct

- Page 39 and 40: obligations were further confirmed

- Page 41 and 42: Moreover, other realms of interacti

- Page 43 and 44: Hence, the Court, whilst recognisin

- Page 45 and 46: for some understanding of the first

- Page 47 and 48: “The Commission’s efforts and i

- Page 49 and 50: trafficking), and especially about

- Page 51 and 52: The central actors in the Trevi fra

- Page 53 and 54: justice and home affairs matters un

- Page 55 and 56: Likewise, the Programme of Action t

- Page 57 and 58: means to repatriate third country n

- Page 59 and 60: “Each Member State shall take app

- Page 61 and 62: “For that purpose, whilst the cho

- Page 63 and 64: limiting national criminal law, it

- Page 65 and 66: “…synthesis of the arrangements

- Page 67 and 68: of Action relating to the reinforce

- Page 69 and 70: the single market and the consequen

- Page 71 and 72: Rather limited in scope and depth,

- Page 73: The need for more openness in the w

- Page 77 and 78: the individual. The building of a m

- Page 79 and 80: Initiatives ranged from the creatio

- Page 81 and 82: etween police forces in matters of

- Page 83 and 84: evenue. 298 Along the same lines, t

- Page 85 and 86: identified in the TEU(M) It was see

- Page 87 and 88: esponsible for the formalisation of

- Page 89 and 90: Indeed, already in 1996, organised

- Page 91 and 92: Finally, besides the political and

- Page 93 and 94: particularly those initiatives that

- Page 95 and 96: and drug trafficking, hence giving

- Page 97 and 98: trade. 356 The Court continued by n

- Page 99 and 100: well as the first protocol. 366 The

- Page 101 and 102: crime is a fluid concept, with loos

- Page 103 and 104: means of transport, telecommunicati

- Page 105 and 106: Chapter 3 The evolution of European

- Page 107 and 108: 1. Treaty of Amsterdam: expansion a

- Page 109 and 110: positions would be suited to define

- Page 111 and 112: The author noted how it was adopted

- Page 113 and 114: 2. The new scope of European Union

- Page 115 and 116: these political declarations, which

- Page 117 and 118: thirty years and epitomises and imp

- Page 119 and 120: phenomenon and of the multifaceted

- Page 121 and 122: within the scope of instruments alr

- Page 123 and 124: Furthermore, the criminalisation of

- Page 125 and 126:

interests (in this case the single

- Page 127 and 128:

More notably, the most significant

- Page 129 and 130:

The Court decided with the Commissi

- Page 131 and 132:

Regardless of the Court having plac

- Page 133 and 134:

in particular fields, thus solidify

- Page 135 and 136:

However, competence to enact legisl

- Page 137 and 138:

months) to third-country national v

- Page 139 and 140:

derogations); 525 others proposed f

- Page 141 and 142:

ecognition of national sentences, p

- Page 143 and 144:

2. The features of the new supranat

- Page 145 and 146:

criminal matters and, if necessary,

- Page 147 and 148:

with a cross border dimension. Ther

- Page 149 and 150:

question of ‘why criminal law’,

- Page 151 and 152:

e affected by ECL law. 562 This dec

- Page 153 and 154:

Chapter 4 Harmonisation of national

- Page 155 and 156:

Harmonisation was felt to be necess

- Page 157 and 158:

matters. Indeed, the European Union

- Page 159 and 160:

This provision portrays a criminal

- Page 161 and 162:

“a structured group of three or m

- Page 163 and 164:

development is in line with the rea

- Page 165 and 166:

economic loss; (e) seizure of aircr

- Page 167 and 168:

Framework Decision, which obliged t

- Page 169 and 170:

possession, among others. 630 A stu

- Page 171 and 172:

Again, the EU’s provision was bro

- Page 173 and 174:

liability is a sensitive issue whic

- Page 175 and 176:

3.2. A focus on minimum maximum pen

- Page 177 and 178:

the threshold demanded by EU law. T

- Page 179 and 180:

of ensuring a degree of homogeneity

- Page 181 and 182:

Framework Decision on trafficking i

- Page 183 and 184:

inging about a harsher criminal law

- Page 185 and 186:

extraterritoriality to nothing less

- Page 187 and 188:

development of the single market -

- Page 189 and 190:

“(… )involves the recognition o

- Page 191 and 192:

These changes in extradition across

- Page 193 and 194:

arguments against extradition of na

- Page 195 and 196:

To be sure, concerns with fundament

- Page 197 and 198:

text of the preamble does not amoun

- Page 199 and 200:

States should not have to use their

- Page 201 and 202:

e partly explained by the fact that

- Page 203 and 204:

“Confidence in the application of

- Page 205 and 206:

2007, Polish authorities requested

- Page 207 and 208:

With these judgements, the Court st

- Page 209 and 210:

does not deem the acts in question

- Page 211 and 212:

discretion in Title VI TEU(A), one

- Page 213 and 214:

Such reasoning led the Court to con

- Page 215 and 216:

was committed by a national abroad

- Page 217 and 218:

Furthermore, the list of types of o

- Page 219 and 220:

“without any further formality be

- Page 221 and 222:

An EEW can only be issued with the

- Page 223 and 224:

“The competent authorities in the

- Page 225 and 226:

prisoners with the view of ‘facil

- Page 227 and 228:

The preamble explains this choice b

- Page 229 and 230:

3.3.3 Probation and alternative san

- Page 231 and 232:

prosecuted elsewhere in the EU. Rat

- Page 233 and 234:

of drugs between two Schengen count

- Page 235 and 236:

definitely bar further prosecution

- Page 237 and 238:

Conclusion The introduction and dev

- Page 239 and 240:

Chapter 6 Conclusion: Towards a Eur

- Page 241 and 242:

Measures adopted along these narrat

- Page 243 and 244:

implementation of Union policies. 9

- Page 245 and 246:

persons acting together; in the fra

- Page 247 and 248:

policies appeared as the main crite

- Page 249 and 250:

preceding any legislative proposal,

- Page 251 and 252:

suggests that mutual recognition wi

- Page 253 and 254:

clear in relation to the EAW. In fa

- Page 255 and 256:

It is beyond the scope of this thes

- Page 257 and 258:

Furthermore, Article 6 TEU(L) confe

- Page 259 and 260:

that may endanger his or her life,

- Page 261 and 262:

communication upon arrest 1012 is u

- Page 263 and 264:

penal values in the future. Similar

- Page 265 and 266:

Member State of execution, irrespec

- Page 267 and 268:

as how long the individual concerne

- Page 269 and 270:

6. A renewed challenge for coherenc

- Page 271 and 272:

Bibliography Books and articles Aba

- Page 273 and 274:

Deen-Racsmany, D., “The European

- Page 275 and 276:

Hinarejos, A., Spencer, J.R., and P

- Page 277 and 278:

Xanthaki (eds) Towards a European C

- Page 279 and 280:

Szymanski, J., “Discretionary Pow

- Page 281 and 282:

Legislation and other sources by ty

- Page 283 and 284:

Council Directive 91/477/EEC of 18

- Page 285 and 286:

Joint Action 96/602/ JHA of 14 Dece

- Page 287 and 288:

Proposals Portuguese Republic, Init

- Page 289 and 290:

supervision order in pre-trial proc

- Page 291 and 292:

Council Doc. 9067/06 on the Proposa

- Page 293 and 294:

Case C-186/98 Criminal proceedings

- Page 295 and 296:

Agreement on the Application betwee

- Page 297:

Websites and links http://www.eurow