Other invasive species in the genus (0–3) 3Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. & Zucc., P. perfoliatum L.,P. polystachyum Wallich ex Meisn., and P. sachalinense F. Schmidtex Maxim. are declared noxious in a number <strong>of</strong> American states.Also Polygonum arenastrum Jord. ex Boreau, P. caespitosumBlume, P. convolvulus L., P. orientale L., and P. aviculare L. arelisted as weeds in the PLANTS Database (USDA, NRSC 2006).A number <strong>of</strong> Polygonum species are native to North America.Polygonum species have a weedy habit and are listed as noxiousweeds in some <strong>of</strong> the American states. Although the latesttaxonomy considers these species as members <strong>of</strong> three differentgenus: Polygonum, Fallopia, and Persicaria (FNA 1993+), they areclosely related taxa and can be considered as congeneric weeds.Aquatic, wetland or riparian species (0–3) 3Although spotted ladysthumb and curlytop knotweed aretypically plants <strong>of</strong> fields, roadsides, gardens, and waste grounds,they <strong>of</strong>ten occur together on riverbanks, edges <strong>of</strong> ponds, lakes,streams, and marshes (DiTomaso and Healy 2003, Stani<strong>for</strong>th andCavers 1979).Total <strong>for</strong> Biological Characteristics and Dispersal 16/25Ecological Amplitude and Distribution ScoreHighly domesticated or a weed <strong>of</strong> agriculture (0–4) 4Both, spotted ladysthumb and curlytop knotweed have long beenassociated with agricultural activities (Stani<strong>for</strong>th and Cavers1979).Known level <strong>of</strong> impact in natural areas (0–6)USpotted ladysthumb and curlytop knotweed are commonly foundon naturally disturbed sites, such as riverbanks, lakeshores, orexposed mud (DiTomaso and Healy 2003, Stani<strong>for</strong>th and Cavers1979). However, ecological impact in natural communities ispoorly documented.Role <strong>of</strong> anthropogenic and natural disturbance in3establishment (0–5)Spotted ladysthumb and curlytop knotweed establish indisturbed communities only (Simmonds 1945a, b). In Ontariocurlytop knotweed is commonly found in naturally disturbedsites such as riverbanks, sandy beaches, exposed mud (Stani<strong>for</strong>thand Cavers 1979).Current global distribution (0–5) 3Spotted ladysthumb and curlytop knotweed are distributedthroughout Europe to 70°N in Norway (Lid and Lid 1994) andRussia; and in Asia, North Africa, North and South America,Australia and New Zealand (Hultén 1968).Extent <strong>of</strong> the species U.S. range and/or occurrence <strong>of</strong><strong>for</strong>mal state or provincial listing (0–5)Spotted ladysthumb and curlytop knotweed are foundthroughout the United States and Canada (Royer and Dickinson1999, USDA, NRCS 2006). Polygonum lapathifolium is declared aweed in Manitoba and Quebec (Royer and Dickinson 1999).Total <strong>for</strong> Ecological Amplitude and Distribution 15/19Feasibility <strong>of</strong> ControlScoreSeed banks (0–3) 3Dorph-Petersen (1925) found that seeds <strong>of</strong> spotted ladysthumband curlytop knotweed remained viable <strong>for</strong> up to 5–7 years. Toole(1946) reported 30 years <strong>of</strong> viability <strong>for</strong> spotted ladysthumb seedsburied in the soil. Chippindale and Milton (1934) found seedsremaining viable in different fields <strong>for</strong> 6, 8, 22, and 68 years.Vegetative regeneration (0–3) 2Vegetative regeneration has not been recorded <strong>for</strong> both species.However, Simmonds (1945a) reported its ability to persist into asecond year after cutting.Level <strong>of</strong> ef<strong>for</strong>t required (0–4) 2Mechanical methods (hand pulling and mowing) can controlpopulations. Improving the drainage will discourage these weedsfrom reestablishment (DiTomaso and Healy 2003).Total <strong>for</strong> Feasibility <strong>of</strong> Control 7/10Total score <strong>for</strong> 4 sections 44/94§5B-90

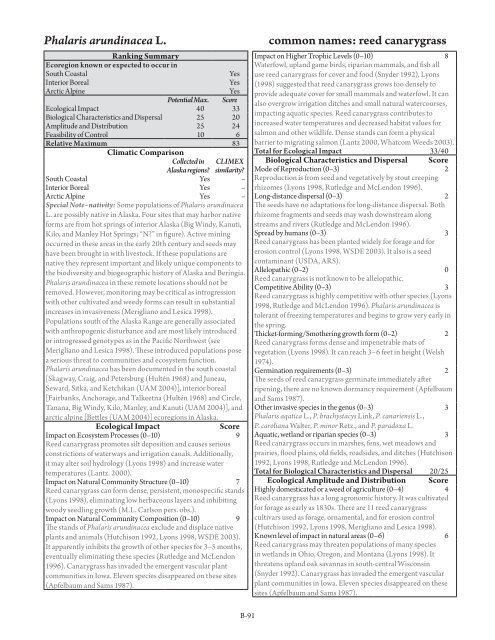

Phalaris arundinacea L.<strong>Ranking</strong> SummaryEcoregion known or expected to occur inSouth CoastalInterior BorealArctic AlpineYesYesYesPotential Max. ScoreEcological Impact 40 33Biological Characteristics and Dispersal 25 20Amplitude and Distribution 25 24Feasibility <strong>of</strong> Control 10 6Relative Maximum 83Climatic ComparisonCollected in<strong>Alaska</strong> regions?CLIMEXsimilarity?South Coastal Yes –Interior Boreal Yes –Arctic Alpine Yes –Special Note–nativity: Some populations <strong>of</strong> Phalaris arundinaceaL. are possibly native in <strong>Alaska</strong>. Four sites that may harbor native<strong>for</strong>ms are from hot springs <strong>of</strong> interior <strong>Alaska</strong> (Big Windy, Kanuti,Kilo, and Manley Hot Springs; “N?” in figure). Active miningoccurred in these areas in the early 20th century and seeds mayhave been brought in with livestock. If these populations arenative they represent important and likely unique components tothe biodiversity and biogeographic history <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alaska</strong> and Beringia.Phalaris arundinacea in these remote locations should not beremoved. However, monitoring may be critical as introgressionwith other cultivated and weedy <strong>for</strong>ms can result in substantialincreases in invasiveness (Merigliano and Lesica 1998).Populations south <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Alaska</strong> Range are generally associatedwith anthropogenic disturbance and are most likely introducedor introgressed genotypes as in the Pacific Northwest (seeMerigliano and Lesica 1998). These introduced populations posea serious threat to communities and ecosystem function.Phalaris arundinacea has been documented in the south coastal[Skagway, Craig, and Petersburg (Hultén 1968) and Juneau,Seward, Sitka, and Ketchikan (UAM 2004)], interior boreal[Fairbanks, Anchorage, and Talkeetna (Hultén 1968) and Circle,Tanana, Big Windy, Kilo, Manley, and Kanuti (UAM 2004)], andarctic alpine [Bettles (UAM 2004)] ecoregions in <strong>Alaska</strong>.Ecological ImpactScoreImpact on Ecosystem Processes (0–10) 9Reed canarygrass promotes silt deposition and causes seriousconstrictions <strong>of</strong> waterways and irrigation canals. Additionally,it may alter soil hydrology (Lyons 1998) and increase watertemperatures (Lantz. 2000).Impact on Natural Community Structure (0–10) 7Reed canarygrass can <strong>for</strong>m dense, persistent, monospecific stands(Lyons 1998), eliminating low herbaceous layers and inhibitingwoody seedling growth (M.L. Carlson pers. obs.).Impact on Natural Community Composition (0–10) 9The stands <strong>of</strong> Phalaris arundinacea exclude and displace nativeplants and animals (Hutchison 1992, Lyons 1998, WSDE 2003).It apparently inhibits the growth <strong>of</strong> other species <strong>for</strong> 3–5 months,eventually eliminating these species (Rutledge and McLendon1996). Canarygrass has invaded the emergent vascular plantcommunities in Iowa. Eleven species disappeared on these sites(Apfelbaum and Sams 1987).common names: reed canarygrassImpact on Higher Trophic Levels (0–10) 8Waterfowl, upland game birds, riparian mammals, and fish alluse reed canarygrass <strong>for</strong> cover and food (Snyder 1992). Lyons(1998) suggested that reed canarygrass grows too densely toprovide adequate cover <strong>for</strong> small mammals and waterfowl. It canalso overgrow irrigation ditches and small natural watercourses,impacting aquatic species. Reed canarygrass contributes toincreased water temperatures and decreased habitat values <strong>for</strong>salmon and other wildlife. Dense stands can <strong>for</strong>m a physicalbarrier to migrating salmon (Lantz 2000, Whatcom Weeds 2003).Total <strong>for</strong> Ecological Impact 33/40Biological Characteristics and Dispersal ScoreMode <strong>of</strong> Reproduction (0–3) 2Reproduction is from seed and vegetatively by stout creepingrhizomes (Lyons 1998, Rutledge and McLendon 1996).Long-distance dispersal (0–3) 2The seeds have no adaptations <strong>for</strong> long-distance dispersal. Bothrhizome fragments and seeds may wash downstream alongstreams and rivers (Rutledge and McLendon 1996).Spread by humans (0–3) 3Reed canarygrass has been planted widely <strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong>age and <strong>for</strong>erosion control (Lyons 1998, WSDE 2003). It also is a seedcontaminant (USDA, ARS).Allelopathic (0–2) 0Reed canarygrass is not known to be allelopathic.Competitive Ability (0–3) 3Reed canarygrass is highly competitive with other species (Lyons1998, Rutledge and McLendon 1996). Phalaris arundinacea istolerant <strong>of</strong> freezing temperatures and begins to grow very early inthe spring.Thicket-<strong>for</strong>ming/Smothering growth <strong>for</strong>m (0–2) 2Reed canarygrass <strong>for</strong>ms dense and impenetrable mats <strong>of</strong>vegetation (Lyons 1998). It can reach 3–6 feet in height (Welsh1974).Germination requirements (0–3) 2The seeds <strong>of</strong> reed canarygrass germinate immediately afterripening, there are no known dormancy requirement (Apfelbaumand Sams 1987).Other invasive species in the genus (0–3) 3Phalaris aqatica L., P. brachystacys Link, P. canariensis L.,P. caroliana Walter, P. minor Retz., and P. paradoxa L.Aquatic, wetland or riparian species (0–3) 3Reed canarygrass occurs in marshes, fens, wet meadows andprairies, flood plains, old fields, roadsides, and ditches (Hutchison1992, Lyons 1998, Rutledge and McLendon 1996).Total <strong>for</strong> Biological Characteristics and Dispersal 20/25Ecological Amplitude and Distribution ScoreHighly domesticated or a weed <strong>of</strong> agriculture (0–4) 4Reed canarygrass has a long agronomic history. It was cultivated<strong>for</strong> <strong>for</strong>age as early as 1830s. There are 11 reed canarygrasscultivars used as <strong>for</strong>age, ornamental, and <strong>for</strong> erosion control(Hutchison 1992, Lyons 1998, Merigliano and Lesica 1998).Known level <strong>of</strong> impact in natural areas (0–6) 6Reed canarygrass may threaten populations <strong>of</strong> many speciesin wetlands in Ohio, Oregon, and Montana (Lyons 1998). Itthreatens upland oak savannas in south-central Wisconsin(Snyder 1992). Canarygrass has invaded the emergent vascularplant communities in Iowa. Eleven species disappeared on thesesites (Apfelbaum and Sams 1987).B-91

- Page 1:

United StatesDepartment ofAgricultu

- Page 5 and 6:

IntroductionThe control of invasive

- Page 7 and 8:

Overview and aimsThe authors, repre

- Page 9 and 10:

The scoring from each system is ver

- Page 11 and 12:

While the relative ranks of species

- Page 13 and 14:

Figure 4. Ranks for Polygonum cuspi

- Page 15 and 16:

Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 17 and 18:

2.3. Potential to be spread by huma

- Page 19 and 20:

3.4. Current global distribution.A

- Page 21 and 22:

obs.), suggesting that establishmen

- Page 23 and 24:

DiscussionThe existing weed risk as

- Page 25 and 26:

AcknowledgementsThe U.S. Forest Ser

- Page 27 and 28:

Prather, T., S. Robins, L. Lake, an

- Page 29:

Appendices

- Page 32 and 33:

EcologicalimpactBiologicalcharacter

- Page 34 and 35:

Appendix A.2.Summary Scores Of Inva

- Page 36 and 37:

EcologicalImpactBiologicalCharacter

- Page 38 and 39:

Alliaria petiolata (Bieb.) Cavara &

- Page 40 and 41:

Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 42 and 43:

Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 44 and 45:

Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 46 and 47:

Germination requirements (0-3) 2See

- Page 48 and 49:

Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik.

- Page 50 and 51:

Spread by humans (0-3) 3The Siberia

- Page 52 and 53:

Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 54 and 55:

Extent of the species U.S. range an

- Page 56 and 57:

Centaurea solstitialis L.Ranking Su

- Page 58 and 59:

Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 60 and 61:

Cirsium vulgare (Savi) TenRanking S

- Page 62 and 63:

Competitive Ability (0-3) 3Due to i

- Page 64 and 65:

Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 66 and 67:

Cytisus scoparius (L.) LinkRanking

- Page 68 and 69:

Germination requirements (0-3) 3Orc

- Page 70 and 71:

Digitalis purpurea L.Ranking Summar

- Page 72 and 73:

Extent of the species U.S. range an

- Page 74 and 75:

Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 76 and 77: Galeopsis bifida Boenn. and G. tetr

- Page 78 and 79: Extent of the species U.S. range an

- Page 80 and 81: Heracleum mantegazzianumSommier & L

- Page 82 and 83: Hesperis matronalis L.Ranking Summa

- Page 84 and 85: Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 86 and 87: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 88 and 89: Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 90 and 91: Competitive Ability (0-3) 3Hydrilla

- Page 92 and 93: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 94 and 95: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 96 and 97: Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 98 and 99: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 100 and 101: Leucanthemum vulgare Lam.Ranking Su

- Page 102 and 103: Competitive Ability (0-3) 2Dalmatia

- Page 104 and 105: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 106 and 107: Lonicera tatarica L. common names:

- Page 108 and 109: Other invasive species in the genus

- Page 110 and 111: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 112 and 113: Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 114 and 115: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 116 and 117: Melilotus alba MedikusRanking Summa

- Page 118 and 119: Melilotus officinalis (L.) Lam.Rank

- Page 120 and 121: Allelopathic (0-2)UThere is no data

- Page 122 and 123: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 124 and 125: Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 128 and 129: Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 130 and 131: Plantago major L.Ranking SummaryEco

- Page 132 and 133: Competitive Ability (0-3) 1Annual b

- Page 134 and 135: Poa pratensis ssp. pratensis L.comm

- Page 136 and 137: Polygonum aviculare L. common names

- Page 138 and 139: Competitive Ability (0-3) 2Black bi

- Page 140 and 141: Other invasive species in the genus

- Page 142 and 143: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 144 and 145: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 146 and 147: Rumex acetosella L.Ranking SummaryE

- Page 148 and 149: Long-distance dispersal (0-3) 3The

- Page 150 and 151: Current global distribution (0-5) 3

- Page 152 and 153: Long-distance dispersal (0-3) 3Ragw

- Page 154 and 155: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 156 and 157: Sonchus arvensis L. common names: f

- Page 158 and 159: Spread by humans (0-3) 3European mo

- Page 160 and 161: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 162 and 163: Stellaria media (L.) Vill.Ranking S

- Page 164 and 165: Taraxacum officinale ssp. officinal

- Page 166 and 167: Aquatic, wetland or riparian specie

- Page 168 and 169: Trifolium hybridum L.Ranking Summar

- Page 170 and 171: Current global distribution (0-5) 3

- Page 172 and 173: Long-distance dispersal (0-3) 2The

- Page 174 and 175: Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 176 and 177:

Vicia villosa RothRanking SummaryEc

- Page 178 and 179:

Current global distribution (0-5) 0

- Page 180 and 181:

Anderson, D. Phalaris. In J. C. Hic

- Page 182 and 183:

Best, K.F., G.G. Bowes, A.G. Thomas

- Page 184 and 185:

Cameron, E. 1935. A study of the na

- Page 186 and 187:

Corbin, J.D., M. Thomsen, J. Alexan

- Page 188 and 189:

Douglas, G.W. and A. MacKinnon. 199

- Page 190 and 191:

Frankton, C. and G.A. Mulligan. 197

- Page 192 and 193:

Haggar, R.J. 1979. Competition betw

- Page 194 and 195:

Howard, J.L. 2002. Descurainia soph

- Page 196 and 197:

Klinkhamer, P.G. and T.J. De Jong.

- Page 198 and 199:

MAFF - Ministry of Agriculture, Foo

- Page 200 and 201:

Miki, S. 1933. On the sea-grasses i

- Page 202 and 203:

Paddock, Raymond, E. III. Environme

- Page 204 and 205:

Proctor, V.W. 1968. Long-distance d

- Page 206 and 207:

Saner, M.A., D.R. Clements, M.R. Ha

- Page 208 and 209:

Stebbins, L.G. 1993. Tragopogon: Go

- Page 210 and 211:

Townshend, J.L. and T.R. Davidson.

- Page 212 and 213:

Washington State Department of Ecol

- Page 214 and 215:

Wolfe-Bellin, K.S. and K.A. Moloney

- Page 216 and 217:

B. Invasiveness Ranking1. Ecologica

- Page 218 and 219:

2.5. Competitive abilityA. Poor com

- Page 220:

4. Feasibility of Control4.1. Seed