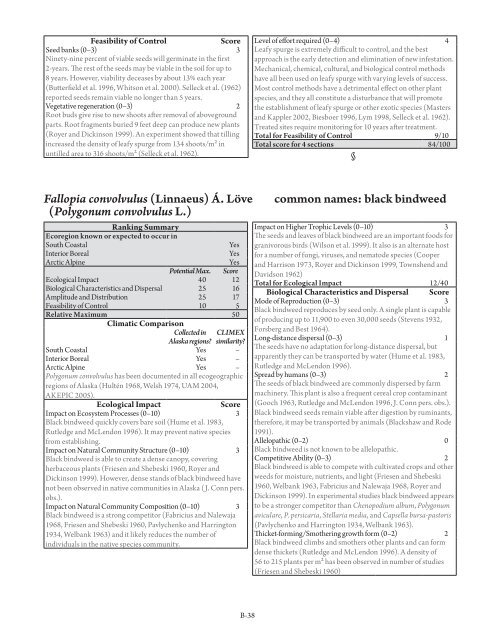

Feasibility <strong>of</strong> ControlScoreSeed banks (0–3) 3Ninety-nine percent <strong>of</strong> viable seeds will germinate in the first2-years. The rest <strong>of</strong> the seeds may be viable in the soil <strong>for</strong> up to8 years. However, viability deceases by about 13% each year(Butterfield et al. 1996, Whitson et al. 2000). Selleck et al. (1962)reported seeds remain viable no longer than 5 years.Vegetative regeneration (0–3) 2Root buds give rise to new shoots after removal <strong>of</strong> abovegroundparts. Root fragments buried 9 feet deep can produce new plants(Royer and Dickinson 1999). An experiment showed that tillingincreased the density <strong>of</strong> leafy spurge from 134 shoots/m² inuntilled area to 316 shoots/m² (Selleck et al. 1962).Level <strong>of</strong> ef<strong>for</strong>t required (0–4) 4Leafy spurge is extremely difficult to control, and the bestapproach is the early detection and elimination <strong>of</strong> new infestation.Mechanical, chemical, cultural, and biological control methodshave all been used on leafy spurge with varying levels <strong>of</strong> success.Most control methods have a detrimental effect on other plantspecies, and they all constitute a disturbance that will promotethe establishment <strong>of</strong> leafy spurge or other exotic species (Mastersand Kappler 2002, Biesboer 1996, Lym 1998, Selleck et al. 1962).Treated sites require monitoring <strong>for</strong> 10 years after treatment.Total <strong>for</strong> Feasibility <strong>of</strong> Control 9/10Total score <strong>for</strong> 4 sections 84/100§Fallopia convolvulus (Linnaeus) Á. Löve(Polygonum convolvulus L.)<strong>Ranking</strong> SummaryEcoregion known or expected to occur inSouth CoastalInterior BorealArctic AlpineYesYesYesPotential Max. ScoreEcological Impact 40 12Biological Characteristics and Dispersal 25 16Amplitude and Distribution 25 17Feasibility <strong>of</strong> Control 10 5Relative Maximum 50Climatic ComparisonCollected in<strong>Alaska</strong> regions?CLIMEXsimilarity?South Coastal Yes –Interior Boreal Yes –Arctic Alpine Yes –Polygonum convolvulus has been documented in all ecogeographicregions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Alaska</strong> (Hultén 1968, Welsh 1974, UAM 2004,AKEPIC 2005).Ecological ImpactScoreImpact on Ecosystem Processes (0–10) 3Black bindweed quickly covers bare soil (Hume et al. 1983,Rutledge and McLendon 1996). It may prevent native speciesfrom establishing.Impact on Natural Community Structure (0–10) 3Black bindweed is able to create a dense canopy, coveringherbaceous plants (Friesen and Shebeski 1960, Royer andDickinson 1999). However, dense stands <strong>of</strong> black bindweed havenot been observed in native communities in <strong>Alaska</strong> (J. Conn pers.obs.).Impact on Natural Community Composition (0–10) 3Black bindweed is a strong competitor (Fabricius and Nalewaja1968, Friesen and Shebeski 1960, Pavlychenko and Harrington1934, Welbank 1963) and it likely reduces the number <strong>of</strong>individuals in the native species community.common names: black bindweedImpact on Higher Trophic Levels (0–10) 3The seeds and leaves <strong>of</strong> black bindweed are an important foods <strong>for</strong>granivorous birds (Wilson et al. 1999). It also is an alternate host<strong>for</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> fungi, viruses, and nematode species (Cooperand Harrison 1973, Royer and Dickinson 1999, Townshend andDavidson 1962)Total <strong>for</strong> Ecological Impact 12/40Biological Characteristics and Dispersal ScoreMode <strong>of</strong> Reproduction (0–3) 3Black bindweed reproduces by seed only. A single plant is capable<strong>of</strong> producing up to 11,900 to even 30,000 seeds (Stevens 1932,Forsberg and Best 1964).Long-distance dispersal (0–3) 1The seeds have no adaptation <strong>for</strong> long-distance dispersal, butapparently they can be transported by water (Hume et al. 1983,Rutledge and McLendon 1996).Spread by humans (0–3) 2The seeds <strong>of</strong> black bindweed are commonly dispersed by farmmachinery. This plant is also a frequent cereal crop contaminant(Gooch 1963, Rutledge and McLendon 1996, J. Conn pers. obs.).Black bindweed seeds remain viable after digestion by ruminants,there<strong>for</strong>e, it may be transported by animals (Blackshaw and Rode1991).Allelopathic (0–2) 0Black bindweed is not known to be allelopathic.Competitive Ability (0–3) 2Black bindweed is able to compete with cultivated crops and otherweeds <strong>for</strong> moisture, nutrients, and light (Friesen and Shebeski1960, Welbank 1963, Fabricius and Nalewaja 1968, Royer andDickinson 1999). In experimental studies black bindweed appearsto be a stronger competitor than Chenopodium album, Polygonumaviculare, P. persicaria, Stellaria media, and Capsella bursa-pastoris(Pavlychenko and Harrington 1934, Welbank 1963).Thicket-<strong>for</strong>ming/Smothering growth <strong>for</strong>m (0–2) 2Black bindweed climbs and smothers other plants and can <strong>for</strong>mdense thickets (Rutledge and McLendon 1996). A density <strong>of</strong>56 to 215 plants per m² has been observed in number <strong>of</strong> studies(Friesen and Shebeski 1960)B-38

Germination requirements (0–3) 2The germination <strong>of</strong> black bindweed seeds is greater on disturbedsites. The disturbance <strong>of</strong> soils apparently reactivates dormantseeds (Milton et al. 1997). However, germination in undisturbedsoil was also recorded (Roberts and Feast 1973).Other invasive species in the genus (0–3) 3Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. & Zucc., P. perfoliatum L.,P. polystachyum Wallich ex Meisn., and P. sachalinense F. Schmidtex Maxim. are declared noxious weeds in number <strong>of</strong> Americanstates (USDA, NRSC 2006). Also Polygonum arenastrum Jord.ex Boreau, P. caespitosum Blume, P. aviculare L., P. orientaleL., P. persicaria L., and P. lapathifolium L. are listed as a weedsin PLANTS Database (USDA, NRSC 2006). A number <strong>of</strong>Polygonum species native to North America have a weedy habitand are listed as noxious weeds in some <strong>of</strong> the American states.Although some <strong>of</strong> the recent taxonomic treatments considersthese as a species <strong>of</strong> three different genera: Polygonum, Fallopia,and Persicaria (FNA 1993+), they are closely related taxa and canbe considered as congeneric weeds.Aquatic, wetland or riparian species (0–3) 1Black bindweed is a common weed in cultivated fields, gardens,roadsides, and waste areas. It may be occasionally found on rivergravel bars (Hume et al. 1983).Total <strong>for</strong> Biological Characteristics and Dispersal 16/24Ecological Amplitude and Distribution ScoreHighly domesticated or a weed <strong>of</strong> agriculture (0–4) 4Black bindweed is a serious weed in crops (Friesen and Shabeski1960, Forsberg and Best 1964).Known level <strong>of</strong> impact in natural areas (0–6) 1Black bindweed has invaded natural communities in RockyMountain National Park (J. Conn pers. obs.).Role <strong>of</strong> anthropogenic and natural disturbance inestablishment (0–5)Black bindweed readily established on cultivated fields anddisturbed grounds (Royer and Dickinson 1999, Welsh 1974).However, it is recorded to establish in grasslands with small-scaleanimal disturbances in Germany (Milton et al. 1997).2Current global distribution (0–5) 5Black bindweed originated from Eurasia. It has now beenintroduced into Africa, South America, Australia, New Zealand,and Oceania (Hultén 1968, USDA, ARS 2003). It has beencollected from arctic regions in <strong>Alaska</strong> (Hultén 1068, UAM2006).Extent <strong>of</strong> the species U.S. range and/or occurrence <strong>of</strong>5<strong>for</strong>mal state or provincial listing (0–5)Black bindweed is found throughout Canada and the UnitedStates. It is declared noxious in <strong>Alaska</strong>, Alberta, Manitoba,Minnesota, Oklahoma, Quebec, and Saskatchewan (<strong>Alaska</strong>Administrative Code 1987, Rice 2006, Royer and Dickinson1999).Total <strong>for</strong> Ecological Amplitude and Distribution 17/25Feasibility <strong>of</strong> ControlScoreSeed banks (0–3) 3Most seeds <strong>of</strong> black bindweed germinate in their first year (Chepil1946). However, seeds remain viable in the soil <strong>for</strong> up to 40 years(Chippendale and Milton 1934). Viability <strong>of</strong> seeds was 5% after4.7 years, and

- Page 1:

United StatesDepartment ofAgricultu

- Page 5 and 6:

IntroductionThe control of invasive

- Page 7 and 8:

Overview and aimsThe authors, repre

- Page 9 and 10:

The scoring from each system is ver

- Page 11 and 12:

While the relative ranks of species

- Page 13 and 14:

Figure 4. Ranks for Polygonum cuspi

- Page 15 and 16:

Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 17 and 18:

2.3. Potential to be spread by huma

- Page 19 and 20:

3.4. Current global distribution.A

- Page 21 and 22:

obs.), suggesting that establishmen

- Page 23 and 24: DiscussionThe existing weed risk as

- Page 25 and 26: AcknowledgementsThe U.S. Forest Ser

- Page 27 and 28: Prather, T., S. Robins, L. Lake, an

- Page 29: Appendices

- Page 32 and 33: EcologicalimpactBiologicalcharacter

- Page 34 and 35: Appendix A.2.Summary Scores Of Inva

- Page 36 and 37: EcologicalImpactBiologicalCharacter

- Page 38 and 39: Alliaria petiolata (Bieb.) Cavara &

- Page 40 and 41: Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 42 and 43: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 44 and 45: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 46 and 47: Germination requirements (0-3) 2See

- Page 48 and 49: Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik.

- Page 50 and 51: Spread by humans (0-3) 3The Siberia

- Page 52 and 53: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 54 and 55: Extent of the species U.S. range an

- Page 56 and 57: Centaurea solstitialis L.Ranking Su

- Page 58 and 59: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 60 and 61: Cirsium vulgare (Savi) TenRanking S

- Page 62 and 63: Competitive Ability (0-3) 3Due to i

- Page 64 and 65: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 66 and 67: Cytisus scoparius (L.) LinkRanking

- Page 68 and 69: Germination requirements (0-3) 3Orc

- Page 70 and 71: Digitalis purpurea L.Ranking Summar

- Page 72 and 73: Extent of the species U.S. range an

- Page 76 and 77: Galeopsis bifida Boenn. and G. tetr

- Page 78 and 79: Extent of the species U.S. range an

- Page 80 and 81: Heracleum mantegazzianumSommier & L

- Page 82 and 83: Hesperis matronalis L.Ranking Summa

- Page 84 and 85: Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 86 and 87: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 88 and 89: Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 90 and 91: Competitive Ability (0-3) 3Hydrilla

- Page 92 and 93: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 94 and 95: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 96 and 97: Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 98 and 99: Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 100 and 101: Leucanthemum vulgare Lam.Ranking Su

- Page 102 and 103: Competitive Ability (0-3) 2Dalmatia

- Page 104 and 105: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 106 and 107: Lonicera tatarica L. common names:

- Page 108 and 109: Other invasive species in the genus

- Page 110 and 111: Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 112 and 113: Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 114 and 115: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 116 and 117: Melilotus alba MedikusRanking Summa

- Page 118 and 119: Melilotus officinalis (L.) Lam.Rank

- Page 120 and 121: Allelopathic (0-2)UThere is no data

- Page 122 and 123: Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 124 and 125:

Biological Characteristics and Disp

- Page 126 and 127:

Other invasive species in the genus

- Page 128 and 129:

Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 130 and 131:

Plantago major L.Ranking SummaryEco

- Page 132 and 133:

Competitive Ability (0-3) 1Annual b

- Page 134 and 135:

Poa pratensis ssp. pratensis L.comm

- Page 136 and 137:

Polygonum aviculare L. common names

- Page 138 and 139:

Competitive Ability (0-3) 2Black bi

- Page 140 and 141:

Other invasive species in the genus

- Page 142 and 143:

Known level of impact in natural ar

- Page 144 and 145:

Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 146 and 147:

Rumex acetosella L.Ranking SummaryE

- Page 148 and 149:

Long-distance dispersal (0-3) 3The

- Page 150 and 151:

Current global distribution (0-5) 3

- Page 152 and 153:

Long-distance dispersal (0-3) 3Ragw

- Page 154 and 155:

Feasibility of ControlScoreSeed ban

- Page 156 and 157:

Sonchus arvensis L. common names: f

- Page 158 and 159:

Spread by humans (0-3) 3European mo

- Page 160 and 161:

Ecological Amplitude and Distributi

- Page 162 and 163:

Stellaria media (L.) Vill.Ranking S

- Page 164 and 165:

Taraxacum officinale ssp. officinal

- Page 166 and 167:

Aquatic, wetland or riparian specie

- Page 168 and 169:

Trifolium hybridum L.Ranking Summar

- Page 170 and 171:

Current global distribution (0-5) 3

- Page 172 and 173:

Long-distance dispersal (0-3) 2The

- Page 174 and 175:

Role of anthropogenic and natural d

- Page 176 and 177:

Vicia villosa RothRanking SummaryEc

- Page 178 and 179:

Current global distribution (0-5) 0

- Page 180 and 181:

Anderson, D. Phalaris. In J. C. Hic

- Page 182 and 183:

Best, K.F., G.G. Bowes, A.G. Thomas

- Page 184 and 185:

Cameron, E. 1935. A study of the na

- Page 186 and 187:

Corbin, J.D., M. Thomsen, J. Alexan

- Page 188 and 189:

Douglas, G.W. and A. MacKinnon. 199

- Page 190 and 191:

Frankton, C. and G.A. Mulligan. 197

- Page 192 and 193:

Haggar, R.J. 1979. Competition betw

- Page 194 and 195:

Howard, J.L. 2002. Descurainia soph

- Page 196 and 197:

Klinkhamer, P.G. and T.J. De Jong.

- Page 198 and 199:

MAFF - Ministry of Agriculture, Foo

- Page 200 and 201:

Miki, S. 1933. On the sea-grasses i

- Page 202 and 203:

Paddock, Raymond, E. III. Environme

- Page 204 and 205:

Proctor, V.W. 1968. Long-distance d

- Page 206 and 207:

Saner, M.A., D.R. Clements, M.R. Ha

- Page 208 and 209:

Stebbins, L.G. 1993. Tragopogon: Go

- Page 210 and 211:

Townshend, J.L. and T.R. Davidson.

- Page 212 and 213:

Washington State Department of Ecol

- Page 214 and 215:

Wolfe-Bellin, K.S. and K.A. Moloney

- Page 216 and 217:

B. Invasiveness Ranking1. Ecologica

- Page 218 and 219:

2.5. Competitive abilityA. Poor com

- Page 220:

4. Feasibility of Control4.1. Seed