CEP Level 3 Manual - Rushmore Hockey Association

CEP Level 3 Manual - Rushmore Hockey Association

CEP Level 3 Manual - Rushmore Hockey Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

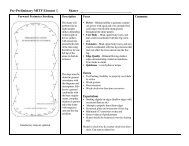

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T SQuotes from elite athletes like these clearlydemonstrate the varied ways athletes mentallyprepare for peak performance. Moreover, becausethe salience of mental preparation for athletes andcoaches is a topic that interests sports psychologists,in the last ten years considerable gains have beenmade in our knowledge on the topic.A Unifying Model of Peak PerformanceA good way to understand mental preparationfor peak performance is to consider a generalframework for organizing how mental skills areinvolved in achieving athletic excellence. One suchframework appears in Figure 1. This framework wasdeveloped by Gould and Damarjian and considersthree important sets of psychological factors thatinteract to produce peak performance in an athlete.These include: the psychological foundation ormake-up/personality of the individual involved;psychology of peak performance strategies; andcoping with adversity strategies.At the base of the pyramid of success is thepsychological foundation or make-up/personality ofthe individual. While our understanding of the roleof personality in sports is far from complete and theidentification of the personality profile of thesuperior athlete has not been identified (Vealey,1992), a number of personality characteristics havePeak Performance StrategiesFoundational Skills & Attributes34 | USA <strong>Hockey</strong> Coaching Education Program <strong>Level</strong> 3 <strong>Manual</strong>been shown to influence the quest for athleticexcellence. For example, an individual’s goalorientations, trait self-confidence and trait anxietyare examples of important factors to consider.Other factors that might be important for futureresearchers to consider would be meaningfulness,hardiness and optimism.The left side of the pyramid consists of peakperformance strategies, which sport psychologistshave spent considerable time identifying asnecessary for peak performance. Examples includesuch things as concentration, a focus onperformance goals, the use of specific mentalpreparation routines and strategies. While the useof such skills will not ensure success, their use “setsthe table for success” by creating a psychologicalclimate that increases the probability of exhibiting agood performance. Hence, when designing mentalskills training programs, decisions should be madeto teach and develop the specific peak performancestrategies most relevant to the sport and athleteinvolved.A common mistake made in mental skillstraining is to focus sole attention on peakperformance strategies. This is problematic becauseathletes must also learn to deal with adversity. Forexample, Gould, Jackson and Finch (1993) foundthat National Champion figure skaters experiencedmore stress after winning their national titles thanCoping with Adversity Strategiesprior to achieving it. Stress resulted from suchfactors as their own and others’ performanceexpectations, time demands, the media, injuries andgeneral life concerns. Therefore, to achieve andmaintain athletic excellence, athletes not only needpsychology of peak performance skills, but alsopsychological coping strategies which can be usedto effectively help them cope with adversity. Suchpsychological skills might involve stressmanagement techniques, thought stopping or socialsupport mechanisms.It is highly recommended that this psychologicalpyramid model of peak performance be consideredwhen considering mental preparation for peakperformance. Consider the personality andpsychological make-up of the athletes that theprogram is aimed at, and if components of theprogram should be focused on developing orenhancing specific personal characteristics ororientations deemed important. In addition, identifythe most important psychology of peakperformance skills to be taught and what strategieswill be most useful in coping with adversity. Mentalskills training programs which address psychologicalfactors at the base and on the two sides of thispyramid have the greatest probability of helpingathletes consistently enhance performance andachieve success.The remainder of this chapter will examineapplied strategies used to mentally prepare athletesfor peak performance. In so doing these specificstrategies will be discussed within the threeelements of this model. This has the advantage offitting specific strategies within a broader moreholistic perspective.The Psychological Make-Up/Personality of theAthleteThis element of the peak performance model isextremely important, but the most difficult to workwith. This results from the fact that it is very difficultto change one’s personality and motivationaldispositions once they are established. However,this is one reason those interested in eliteperformance should be interested and informed ofthe youth sport research. Children’s sport researchhas identified the important role perceivedcompetence plays in motivation and achievement(Weiss & Chaumeton, 1992), how positive coachingpractices facilitate the development of positive selfesteem,reduce trait anxiety and lower dropout rates(Barnett et al., 1992; Smith & Smoll, 1995; Smith,Smoll & Barnett, 1995), how one’s goal orientationsinfluence achievement behavior (Duda, 1993) andwhat makes sports stressful for young athletes andhow levels of stress can be reduced.While it is much easier to develop positivepsychological attributes through effective coachingpractices when performers are young, this does notimply that nothing can be done in this area byseasoned adult competitors. When asked to consultwith elite performers who are experiencingperformance difficulties, highly respected NorthAmerican mental training consultant Ken Ravizza,for example, spends considerable time having themdiscuss why they participate in their sport and whatmeaning it has for them. It is his opinion thatathletes perform much better when they are notquestioning the reasons for their involvement andit’s meaningfulness. In a similar vein, Terry Orlick(1986) begins his mental training efforts by havingathletes consider their long-term goals for sportparticipation, including a discussion of their dreamsand overall aspirations. Finally, it must berecognized that meaningfulness differs greatlyacross athletes. Some may have their lives in totalorder with clear sport and non-sport goals andobjectives. Others, like former diving great GregLouganis, may have (had) a life out of sports whichis totally chaotic (Louganis & Marcus, 1995). Forthese individuals, however, sport serves as a refugeor safe haven from their troubled outside world.And still others may be in a process of transition,where the once clear sport and life objectives andgoals are being questioned as they face retirementfrom sports (Danish, Petitpas & Hale, 1995; Murphy,1995).Lastly, seasoned athletes may change or learn tomore effectively deal with their motivationalorientations and personality characteristics. Forinstance, an elite athlete who is very outcomeorientedand focuses primary attention on winningmay learn that thinking about the outcome ofcompetition close to, or during performance ofteninterferes with achieving his objective. Hence, he orshe learns not to focus on winning, before or duringthe competition. It is only effective to do so at othertimes. Similarly, it has been recently found thatperfectionism is associated with sport burnout inelite junior tennis players (Gould, Udry, Tuffey &Sport Psychology | 35