CEP Level 3 Manual - Rushmore Hockey Association

CEP Level 3 Manual - Rushmore Hockey Association

CEP Level 3 Manual - Rushmore Hockey Association

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

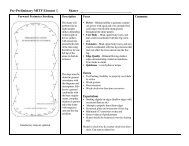

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T SLoehr, in press). However, many of the mosteffective world class athletes are perfectionistic intheir orientations. However, they have learned todeal with their perfectionistic tendencies in apositive manner, allowing these tendencies tofacilitate, as opposed to inhibit their development.Peak Performance StrategiesBoth research and the experience of sportpsychologists have taught a great deal about thepsychological strategies needed to consistentlyproduce outstanding performances. While it isbeyond the scope of this review to dismiss all of thework in this area, six strategies that are particularlyimportant will be examined.One reason outstanding performances occur isbecause top athletes set goals (Burton, 1992). Wehave learned, however, that not all goals are equal interms of assisting individuals in achieving peakperformances. Goals must be specific as opposedto general, difficult but realistic, and arranged in aladder or staircase progression of short-term goalsleading to more long range goals. They should alsobe frequently evaluated, and, if needed, modified.Finally, it is most important that a systematicapproach to goal setting be taken and that theathlete be intimately involved in the goal settingprocess.While setting and working towards goalachievement is important, goals alone are notenough. Athletes must make a commitment toachieving excellence. In their extensive study ofOlympic athletes, for example, Orlick andPartington (1988) found that those who performedup to, or exceeded their personal bests in Olympiccompetitions were totally committed to achievingexcellence. Similarly, in their study of SeoulOlympic wrestlers, Gould, Eklund and Jackson(1992) found that a commitment to excellence wasa prerequisite to outstanding performance. It is veryimportant to recognize that this commitment toexcellence does not occur just on game days or incompetitions, but at practices as well. In fact, manyapplied sports psychologists now contend thatsetting goals, mentally preparing and making acommitment in practices, is, as or more critical thanat competitions for achieving consistent athleticsuccess.Research in the last decade has emphasized theimportance of focusing on performance as opposedto outcome goals during competition (Buront, 1992;Duda, 1993; Gould, 1983; Orlick & Partington,1988). In particular, performance goals are selfreferencedperformance objectives such asimproving one’s time in a 100 meter swim or makinga certain percentage of foul shots in basketball,while outcome goals focus on other-basedobjectives like winning or placing higher than aparticular opponent. The logic behind thisrecommendation is that performance goals aremore flexible and in one’s control, as they are notdependent on another competitor while outcomegoals are less flexible and dependent on another’sperformance. Because of this, outcome goals oftencreate anxiety and interrupt psychologicalfunctioning (Burton, 1992).An excellent example of focusing onperformance goals in competition was given byOlympic gold medal skier Tommy Moe. Whenasked by the media prior to this gold medalperformance whether he was thinking aboutwinning (an outcome goal), Moe indicated that hecertainly wanted to win, but had found in the pastthat when he thinks about winning while racing, hetightens up and does not perform well. He skis athis best when he focuses on “letting his outside ski,run” and keeping his “hands out in front” of himself- clear performance goals.The above is not to imply that elite performersdo not hold outcome goals. Most have these typesof goals and find them very salient (Hardy, Jones, &Gould, in press). However, in the heat ofcompetition they do not focus on these outcomegoals - only on what they can control; theirperformance objectives.An excellent way elite athletes prepare for peakperformance is by employing imagery (Gould &Damarjian, in press a; Orlick, 1986; Vealey andWalters, 1993). They see and especially feelthemselves being successful. Moreover, theyemploy imagery in a number of ways: for errorcorrection, to mentally prepare, to see themselvesachieving goals, and facilitating recovery frominjury. It is no wonder that Orlick and Partington(1988) found imagery to be a key variableseparating the more and less successful performers.One reason top performers achieve athleticexcellence on a consistent basis is that they havedeveloped mental and physical preparation routinesand adhere to these in the face of adversity andfailure (Boutcher, 1990; Cohn, 1990). Gould et al.(1992) found, for instance, that more successfulOlympic wrestlers had better developed mentalpreparation routines than their less successfulcounterparts. Hence, they utilize systematic ways ofphysically and mentally readying themselves.Finally, it has been consistently shown that moresuccessful competitors are more confident thantheir less successful counterparts (McAuley, 1992;Williams & Krane, 1993). Moreover, theseindividuals develop confidence via all four ofBandura’s (1984) sources of efficacy [performanceaccomplishments, vicarious experience, persuasionand physiological status interpretation and control]with performance accomplishments being the mostimportant source of information. Elite athleteconfidence comes from employing the previousmentioned psychology of peak performancestrategies on a regular basis.Coping with Adversity StrategiesAn athlete can have good foundational skills(motivational orientations, perspective on themeaningfulness of involvement) and strong peakperformance strategies and still fail to achieveconsistent success. The reason for this is that theyhave not developed skills for coping with adversity.And no matter how successful athletes have been inthe past, they will be faced with adversity. In thestudy of U.S. national champion figure skaters, forinstance, it was found that the vast majority of theseathletes experienced more stress after, as opposedto prior to, winning their championship. Stressresulted from such things as increased self and otherperformance expectations, media attention, andtravel demands (Gould, Jackson & Finch, 1993).Moreover, the longer an elite athlete’s career themore likely he or she will sustain a major injury. Forinstance, most members of the U.S. Ski Team havesustained at least one major season-ending injuryand in so doing had to cope with the stress of theinjury and the challenge of physically recoveringfrom it. It is imperative that the successful performerdevelop coping strategies for dealing with adversity.A first step in preparing to cope with adversity isto learn to expect the unexpected. From the studyof 1988 Olympic wrestlers (Gould, Eklund &Jackson, 1992) for instance, it was learned that more(versus less successful) competitors were positive intheir orientation, but did not expect things to runperfectly and actually anticipated unexpectedcircumstances such as bad calls from officials,transportation hassles and delays in the event. Bydoing so, these athletes were better able to copewith such events when they actually arose. Theirless successful counterparts, had experienced thesame unexpected circumstances in internationalcompetition in the past, but did not expect them tooccur in “their” Olympics. They became frustratedand distraught when they did so.Given the above, it is effective to prepare eliteathletes for major competitions by holding teamdiscussions where potential unexpected events andsources of stress were identified prior to acompetition and ways to cope with them if theyarose. For example, in helping elite figure skatersmentally prepare for the U.S. senior nationals(especially their first time), parents and loved onescan unintentionally interfere with a skater’s mentalpreparation (e.g., the skater needs to be alone thenight before the competition but the parents insiston taking him or her out to dinner). To remedy thisstate of affairs, skaters are instructed to inform theirparents of their mental preparation needs prior tothe competition and actually plan family reunionsand get togethers. In a similar vein, discussions wereheld with the U.S. freestyle ski team prior to theLillihammer Games, where securing tickets forsignificant others and increased security (soldierswith machine guns) were identified as potentialstress sources. To cope with the first stressor, theathletes on the team organized a ticket exchangesystem among themselves so those athletes needingtickets could obtain unused ones from other teammembers. Nothing could be done to change thesecond potential stressor, but by recognizing thatsuch feelings would occur, the athletes felt betterprepared to deal with them.Lastly, great coaches like the former Universityof North Carolina Chapel Hills’ basketball coach,Dean Smith, prepared their teams for theunexpected through game simulations. Forexample, Coach Smith ended every practice with areferee on the court and the clock running with histeam in varying circumstances (down by 2 and ondefense, up by 3 with the ball). By doing so, overthe course of the season his teams becomeaccustomed to dealing with a variety of late gamepressure situations and tactical and mentalstrategies for dealing with them. Hence, theypracticed unexpected situations and how toeffectively cope with them.36 | USA <strong>Hockey</strong> Coaching Education Program <strong>Level</strong> 3 <strong>Manual</strong>Sport Psychology | 37