Global Tuberculosis Report -- 2012.pdf

Global Tuberculosis Report -- 2012.pdf

Global Tuberculosis Report -- 2012.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

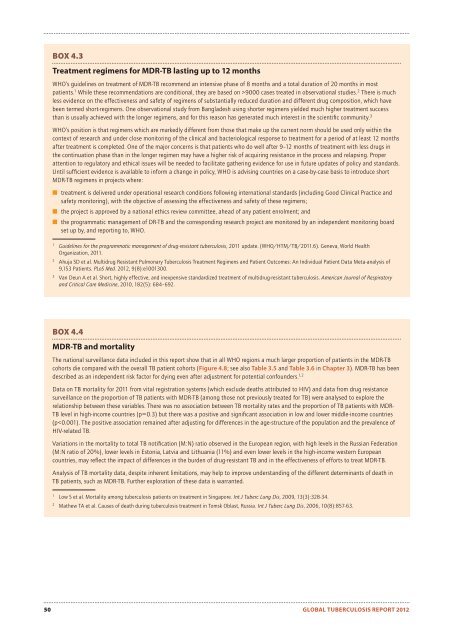

BOX 4.3Treatment regimens for MDR-TB lasting up to 12 monthsWHO’s guidelines on treatment of MDR-TB recommend an intensive phase of 8 months and a total duration of 20 months in mostpatients. 1 While these recommendations are conditional, they are based on >9000 cases treated in observational studies. 2 There is muchless evidence on the effectiveness and safety of regimens of substantially reduced duration and different drug composition, which havebeen termed short-regimens. One observational study from Bangladesh using shorter regimens yielded much higher treatment successthan is usually achieved with the longer regimens, and for this reason has generated much interest in the scientifi c community. 3WHO’s position is that regimens which are markedly different from those that make up the current norm should be used only within thecontext of research and under close monitoring of the clinical and bacteriological response to treatment for a period of at least 12 monthsafter treatment is completed. One of the major concerns is that patients who do well after 9–12 months of treatment with less drugs inthe continuation phase than in the longer regimen may have a higher risk of acquiring resistance in the process and relapsing. Properattention to regulatory and ethical issues will be needed to facilitate gathering evidence for use in future updates of policy and standards.Until suffi cient evidence is available to inform a change in policy, WHO is advising countries on a case-by-case basis to introduce shortMDR-TB regimens in projects where:■ treatment is delivered under operational research conditions following international standards (including Good Clinical Practice andsafety monitoring), with the objective of assessing the effectiveness and safety of these regimens;■ the project is approved by a national ethics review committee, ahead of any patient enrolment; and■ the programmatic management of DR-TB and the corresponding research project are monitored by an independent monitoring boardset up by, and reporting to, WHO.1Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2011 update. (WHO/HTM/TB/2011.6). Geneva, World HealthOrganization, 2011.2Ahuja SD et al. Multidrug Resistant Pulmonary <strong>Tuberculosis</strong> Treatment Regimens and Patient Outcomes: An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis of9,153 Patients. PLoS Med. 2012, 9(8):e1001300.3Van Deun A et al. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. American Journal of Respiratoryand Critical Care Medicine, 2010, 182(5): 684–692.BOX 4.4MDR-TB and mortalityThe national surveillance data included in this report show that in all WHO regions a much larger proportion of patients in the MDR-TBcohorts die compared with the overall TB patient cohorts (Figure 4.8; see also Table 3.5 and Table 3.6 in Chapter 3). MDR-TB has beendescribed as an independent risk factor for dying even after adjustment for potential confounders. 1,2Data on TB mortality for 2011 from vital registration systems (which exclude deaths attributed to HIV) and data from drug resistancesurveillance on the proportion of TB patients with MDR-TB (among those not previously treated for TB) were analysed to explore therelationship between these variables. There was no association between TB mortality rates and the proportion of TB patients with MDR-TB level in high-income countries (p=0.3) but there was a positive and signifi cant association in low and lower middle-income countries(p