SHAPING THE FUTURE HOW CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS CAN POWER HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

23XELCz

23XELCz

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

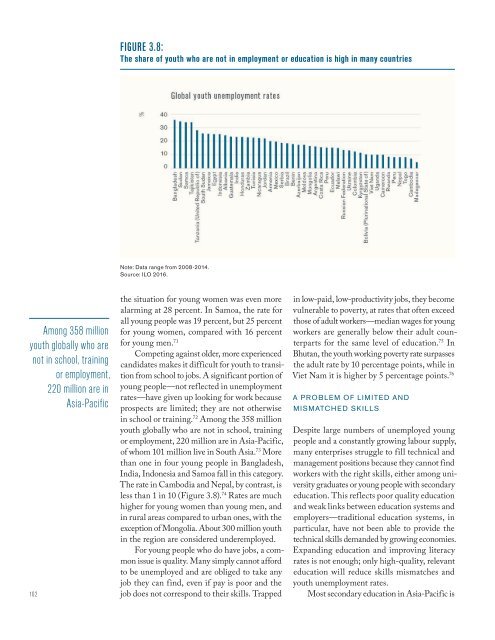

FIGURE 3.8:<br />

The share of youth who are not in employment or education is high in many countries<br />

Note: Data range from 2008-2014.<br />

Source: ILO 2016.<br />

Among 358 million<br />

youth globally who are<br />

not in school, training<br />

or employment,<br />

220 million are in<br />

Asia-Pacific<br />

102<br />

the situation for young women was even more<br />

alarming at 28 percent. In Samoa, the rate for<br />

all young people was 19 percent, but 25 percent<br />

for young women, compared with 16 percent<br />

for young men. 71<br />

Competing against older, more experienced<br />

candidates makes it difficult for youth to transition<br />

from school to jobs. A significant portion of<br />

young people—not reflected in unemployment<br />

rates—have given up looking for work because<br />

prospects are limited; they are not otherwise<br />

in school or training. 72 Among the 358 million<br />

youth globally who are not in school, training<br />

or employment, 220 million are in Asia-Pacific,<br />

of whom 101 million live in South Asia. 73 More<br />

than one in four young people in Bangladesh,<br />

India, Indonesia and Samoa fall in this category.<br />

The rate in Cambodia and Nepal, by contrast, is<br />

less than 1 in 10 (Figure 3.8). 74 Rates are much<br />

higher for young women than young men, and<br />

in rural areas compared to urban ones, with the<br />

exception of Mongolia. About 300 million youth<br />

in the region are considered underemployed.<br />

For young people who do have jobs, a common<br />

issue is quality. Many simply cannot afford<br />

to be unemployed and are obliged to take any<br />

job they can find, even if pay is poor and the<br />

job does not correspond to their skills. Trapped<br />

in low-paid, low-productivity jobs, they become<br />

vulnerable to poverty, at rates that often exceed<br />

those of adult workers—median wages for young<br />

workers are generally below their adult counterparts<br />

for the same level of education. 75 In<br />

Bhutan, the youth working poverty rate surpasses<br />

the adult rate by 10 percentage points, while in<br />

Viet Nam it is higher by 5 percentage points. 76<br />

A PROBLEM OF LIMITED AND<br />

MISMATCHED SKILLS<br />

Despite large numbers of unemployed young<br />

people and a constantly growing labour supply,<br />

many enterprises struggle to fill technical and<br />

management positions because they cannot find<br />

workers with the right skills, either among university<br />

graduates or young people with secondary<br />

education. This reflects poor quality education<br />

and weak links between education systems and<br />

employers—traditional education systems, in<br />

particular, have not been able to provide the<br />

technical skills demanded by growing economies.<br />

Expanding education and improving literacy<br />

rates is not enough; only high-quality, relevant<br />

education will reduce skills mismatches and<br />

youth unemployment rates.<br />

Most secondary education in Asia-Pacific is