WEST KIMBERLEY PLACE REPORT - Department of Sustainability ...

WEST KIMBERLEY PLACE REPORT - Department of Sustainability ...

WEST KIMBERLEY PLACE REPORT - Department of Sustainability ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

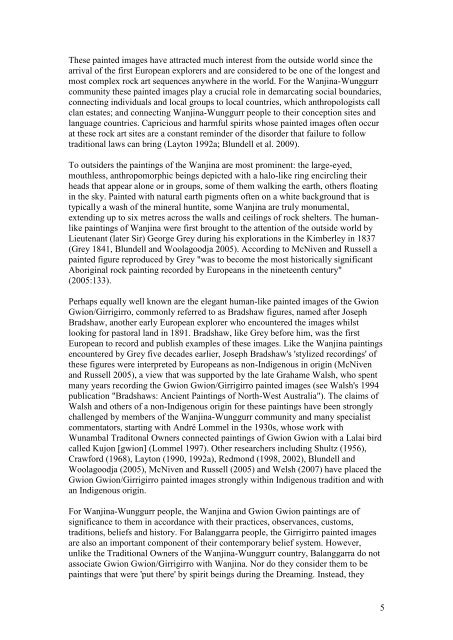

These painted images have attracted much interest from the outside world since the<br />

arrival <strong>of</strong> the first European explorers and are considered to be one <strong>of</strong> the longest and<br />

most complex rock art sequences anywhere in the world. For the Wanjina-Wunggurr<br />

community these painted images play a crucial role in demarcating social boundaries,<br />

connecting individuals and local groups to local countries, which anthropologists call<br />

clan estates; and connecting Wanjina-Wunggurr people to their conception sites and<br />

language countries. Capricious and harmful spirits whose painted images <strong>of</strong>ten occur<br />

at these rock art sites are a constant reminder <strong>of</strong> the disorder that failure to follow<br />

traditional laws can bring (Layton 1992a; Blundell et al. 2009).<br />

To outsiders the paintings <strong>of</strong> the Wanjina are most prominent: the large-eyed,<br />

mouthless, anthropomorphic beings depicted with a halo-like ring encircling their<br />

heads that appear alone or in groups, some <strong>of</strong> them walking the earth, others floating<br />

in the sky. Painted with natural earth pigments <strong>of</strong>ten on a white background that is<br />

typically a wash <strong>of</strong> the mineral huntite, some Wanjina are truly monumental,<br />

extending up to six metres across the walls and ceilings <strong>of</strong> rock shelters. The humanlike<br />

paintings <strong>of</strong> Wanjina were first brought to the attention <strong>of</strong> the outside world by<br />

Lieutenant (later Sir) George Grey during his explorations in the Kimberley in 1837<br />

(Grey 1841, Blundell and Woolagoodja 2005). According to McNiven and Russell a<br />

painted figure reproduced by Grey "was to become the most historically significant<br />

Aboriginal rock painting recorded by Europeans in the nineteenth century"<br />

(2005:133).<br />

Perhaps equally well known are the elegant human-like painted images <strong>of</strong> the Gwion<br />

Gwion/Girrigirro, commonly referred to as Bradshaw figures, named after Joseph<br />

Bradshaw, another early European explorer who encountered the images whilst<br />

looking for pastoral land in 1891. Bradshaw, like Grey before him, was the first<br />

European to record and publish examples <strong>of</strong> these images. Like the Wanjina paintings<br />

encountered by Grey five decades earlier, Joseph Bradshaw's 'stylized recordings' <strong>of</strong><br />

these figures were interpreted by Europeans as non-Indigenous in origin (McNiven<br />

and Russell 2005), a view that was supported by the late Grahame Walsh, who spent<br />

many years recording the Gwion Gwion/Girrigirro painted images (see Walsh's 1994<br />

publication "Bradshaws: Ancient Paintings <strong>of</strong> North-West Australia"). The claims <strong>of</strong><br />

Walsh and others <strong>of</strong> a non-Indigenous origin for these paintings have been strongly<br />

challenged by members <strong>of</strong> the Wanjina-Wunggurr community and many specialist<br />

commentators, starting with André Lommel in the 1930s, whose work with<br />

Wunambal Traditonal Owners connected paintings <strong>of</strong> Gwion Gwion with a Lalai bird<br />

called Kujon [gwion] (Lommel 1997). Other researchers including Shultz (1956),<br />

Crawford (1968), Layton (1990, 1992a), Redmond (1998, 2002), Blundell and<br />

Woolagoodja (2005), McNiven and Russell (2005) and Welsh (2007) have placed the<br />

Gwion Gwion/Girrigirro painted images strongly within Indigenous tradition and with<br />

an Indigenous origin.<br />

For Wanjina-Wunggurr people, the Wanjina and Gwion Gwion paintings are <strong>of</strong><br />

significance to them in accordance with their practices, observances, customs,<br />

traditions, beliefs and history. For Balanggarra people, the Girrigirro painted images<br />

are also an important component <strong>of</strong> their contemporary belief system. However,<br />

unlike the Traditional Owners <strong>of</strong> the Wanjina-Wunggurr country, Balanggarra do not<br />

associate Gwion Gwion/Girrigirro with Wanjina. Nor do they consider them to be<br />

paintings that were 'put there' by spirit beings during the Dreaming. Instead, they<br />

5