AMS Philadelphia 2009 Abstracts - American Musicological Society

AMS Philadelphia 2009 Abstracts - American Musicological Society

AMS Philadelphia 2009 Abstracts - American Musicological Society

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

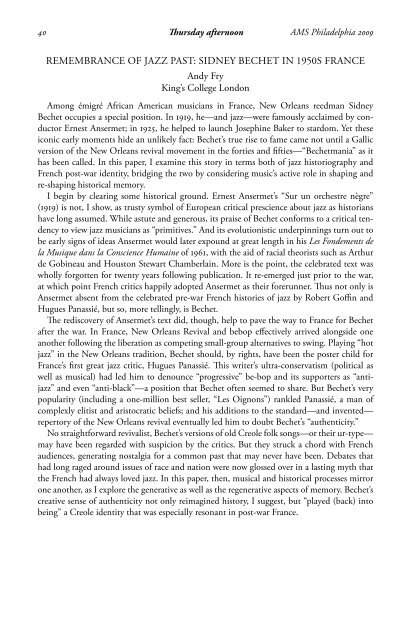

40 Thursday afternoon <strong>AMS</strong> <strong>Philadelphia</strong> <strong>2009</strong><br />

REMEMBRANCE OF JAZZ PAST: SIDNEY BECHET IN 1950S FRANCE<br />

Andy Fry<br />

King’s College London<br />

Among émigré African <strong>American</strong> musicians in France, New Orleans reedman Sidney<br />

Bechet occupies a special position. In 1919, he—and jazz—were famously acclaimed by conductor<br />

Ernest Ansermet; in 1925, he helped to launch Josephine Baker to stardom. Yet these<br />

iconic early moments hide an unlikely fact: Bechet’s true rise to fame came not until a Gallic<br />

version of the New Orleans revival movement in the forties and fifties—“Bechetmania” as it<br />

has been called. In this paper, I examine this story in terms both of jazz historiography and<br />

French post-war identity, bridging the two by considering music’s active role in shaping and<br />

re-shaping historical memory.<br />

I begin by clearing some historical ground. Ernest Ansermet’s “Sur un orchestre nègre”<br />

(1919) is not, I show, as trusty symbol of European critical prescience about jazz as historians<br />

have long assumed. While astute and generous, its praise of Bechet conforms to a critical tendency<br />

to view jazz musicians as “primitives.” And its evolutionistic underpinnings turn out to<br />

be early signs of ideas Ansermet would later expound at great length in his Les Fondements de<br />

la Musique dans la Conscience Humaine of 1961, with the aid of racial theorists such as Arthur<br />

de Gobineau and Houston Stewart Chamberlain. More is the point, the celebrated text was<br />

wholly forgotten for twenty years following publication. It re-emerged just prior to the war,<br />

at which point French critics happily adopted Ansermet as their forerunner. Thus not only is<br />

Ansermet absent from the celebrated pre-war French histories of jazz by Robert Goffin and<br />

Hugues Panassié, but so, more tellingly, is Bechet.<br />

The rediscovery of Ansermet’s text did, though, help to pave the way to France for Bechet<br />

after the war. In France, New Orleans Revival and bebop effectively arrived alongside one<br />

another following the liberation as competing small-group alternatives to swing. Playing “hot<br />

jazz” in the New Orleans tradition, Bechet should, by rights, have been the poster child for<br />

France’s first great jazz critic, Hugues Panassié. This writer’s ultra-conservatism (political as<br />

well as musical) had led him to denounce “progressive” be-bop and its supporters as “antijazz”<br />

and even “anti-black”—a position that Bechet often seemed to share. But Bechet’s very<br />

popularity (including a one-million best seller, “Les Oignons”) rankled Panassié, a man of<br />

complexly elitist and aristocratic beliefs; and his additions to the standard—and invented—<br />

repertory of the New Orleans revival eventually led him to doubt Bechet’s “authenticity.”<br />

No straightforward revivalist, Bechet’s versions of old Creole folk songs—or their ur-type—<br />

may have been regarded with suspicion by the critics. But they struck a chord with French<br />

audiences, generating nostalgia for a common past that may never have been. Debates that<br />

had long raged around issues of race and nation were now glossed over in a lasting myth that<br />

the French had always loved jazz. In this paper, then, musical and historical processes mirror<br />

one another, as I explore the generative as well as the regenerative aspects of memory. Bechet’s<br />

creative sense of authenticity not only reimagined history, I suggest, but “played (back) into<br />

being” a Creole identity that was especially resonant in post-war France.